From the instant to the moment

Out of all the exemplary photographers considered in this book, Cartier-Bresson is undoubtedly the one that reaches the widest audience – at least in our countries. This is perhaps – for that very reason – why he is the most difficult to outline. His photographic subject – instead of pushing him to the limits of a privileged virtuality of photography – is the result of a body of tensions. The most fundamental, the one that holds all others, is the paradoxical combination of composition and grasping. Cartier-Bresson composes insofar as he is grasped. And he is grasped insofar as he composes. This, of course, supposes a certain type of composition and a certain type of grasping.

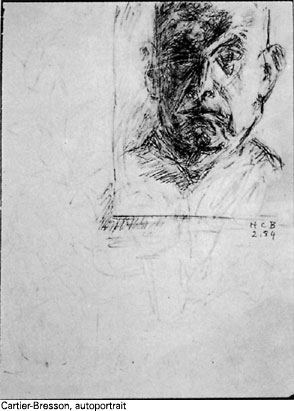

Considering this, we own an irreplaceable document. It is a drawn self-portrait signed H.C.B., carefully dated ‘2-84’. The ‘Cahiers de la Photographie’ judiciously used it as the cover of their special issue, probably as a key for the ensemble (*).

Everything is there, starting with the layout. The drawer placed a rectangular sheet high up in front of him. In this rectangle, he immediately inscribed a new rectangle in the top right hand corner. The latter takes up more than a quarter of the page, meaning that it is massive. Hence, our outlook moves up towards the top right hand corner to the hence-compressed part, to be immediately and brutally pulled-down right-left, top-bottom, back-front, compressed-decompressed, in an oblique déboulé. Thereby, the most compositional composition there can be, interweaving two rectangles (whose sides are almost in golden proportion like the 35 mm rectangle), turns around itself and derails us, because the upright, lateralized primates that we are spontaneously articulate a bottom-high, left-right, front-back show, with the weights at the bottom rather than at the top. To give good measure, the base of the inserted rectangle’s frame has been shaded to stand out more and better fall on us, while precipitating its point towards the left point of the bottom of the sheet in a double final thrust.

|

The abstract topology doubles itself in the imagetic party. The top right rectangle contains the strongly drawn head and the beginning of the shoulders; the rest of the page is greying with the barely-sketched bust in the same oblique déboulé. The game starts over inside the detailed rectangle: the head is more to the right, the bust to the left; the ear on the right is larger, almost unstuck, the left ear is receding; the right eye in the light is wide open whilst the left eye is in the shade; same game in the chin and the pointing nose. Above the right eye, a block of light resumes the general topology and cybernetic with the strength of a bone that would stick out from the forehead, triggering – with a group of vertical and horizontal scars zigzags going in every direction – yet always confirming the oblique déboulé by their resultants.

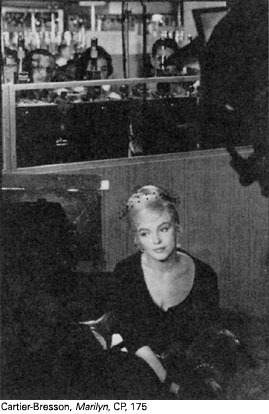

Through the photographs, this topology finds its lightning speed in the zigzag plunge of a sheet and a magazine (CP, 144), in the zigzag of a family in the opposite page (CP, 145), in the zigzag of palisades seen from above (CP, 143). It supports the resting figures of CPJ52 and 153, and Marilyn (**, CP, 75) interviewed under the domineering instances of the cinema. Assuredly, we find the variants, for instance left-right (C, 141) instead of right-left (CP, 140); or still, a vertical déboulé (CP, 149, 148). But for the essence, the party of existence is constant.

|

Time follows space or concords with it. Because – on the lookout for such a blend of composition and stupefaction – our ‘visual organ’ is seen as a ‘disturbing agent’ and can only activate itself in the ‘decisive instant’. There are, indeed, particular instants, what the Greek referred to as a ‘tukHè’ (meeting), from ‘tungkHanein’ (verb meeting). A ‘tukHè’ is a confluence, a punctual conjunction of several series of heterogeneous events (the tile on the roof + the forehead of the passer-by) which – for a fraction of second – create a very dense present (the fracture of the skull), by which the instant becomes a moment, with the weight of the moment (momentum, movimentum) that the instant does not have. We see that the Greek notion of ‘tukHè’ is a lot richer than that of ‘hazard’, from the Arab al-zahr, dice throw, and of ‘chance’, ‘cadentia’, which only translates the fall of the dice. However, to capture the instant that becomes moment, photography is more talented than painting because, since it is indicial (lat.indicium), it registers series of multiple elements, and the meaning there is usually borne from the coincidence of several insignificances.

It is strange that Cartier-Bresson should have chosen the title L’instant decisif, and then went in the same breath mention the Cardinal de Retz, who speaks of ‘decisive moment’. The Americans hit the bull’s eye by entitling The decisive moment. Now, ‘or’ (hora) ‘now’, the negligence – or the subtlety – of the contrast between the title and the epitaph in French does remain suggestive. For the instant-moment suite allows to understand that Cartier-Bresson excluded the violent ‘tukHai’, those that attracted Weegee as he spent most of his nights following the New York police around, photographing a corpse on a pavement here, the spectators of a murder there. Violence moves from the moment to the instant, not from the instant to the moment. Cartier-Bresson will always avoid brutal shocks and ecstatic experiences to maintain himself in a daily and average psychology that was only compatible with his compositional grasping.

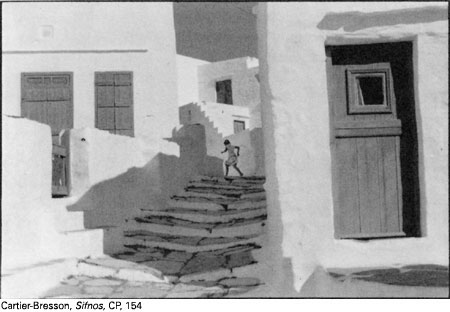

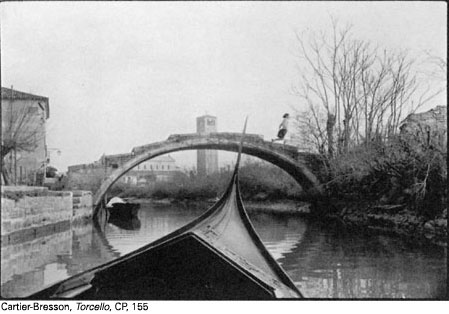

We celebrated his diabolical quickness rightly. For, to grasp-construct Torcello’s instant-moment in 1954 (****CP, 155), we needed for the tip of the ship’s prow to align itself with the point of the steeple and the chimney of the house. This point – that crossed the lowered vault of the deck like a needle runs across a dial – is now between the steeple and the young girl at the exact moment when she was about to enter the stripped clump of trees, without disappearing yet (making, here again, the space on the top right hand side the place where the composition turns around). We still needed to preview (Ansel Adams) that the steeple would create a median; under the lowered vault, the graphic weight of the violence of the right tip would be balanced by the conjunction – to the left – of a long building, with a ship meeting the one on which we are standing… The amount of heterogeneous compatibilised series is not less extraordinary when a little girl climbs up some stairs in Sifnos (***CP, 154).

|

|

H.C.B.’s other characteristics follow the compositional grasping with its oblique déboulé. 1) The integrity of the negative attests of the shock received; it is declared by the black border, which is a small piece of negative. 2) The indicium-frame represented by this border slides to the index-frame, almost pictorially compositional. 3) The simultaneously global and detailed perceptive-motor field effect – in order to run from one side to the other of the show in one go – supposes the subtlety of greys and excludes the photographic colour, too blurry. 4) The show, where photonic indicia almost become full referential signs, must be evident. Even the puddles are drawn: ‘by placing the camera more or less close from the subject, we draw the detail’. 5) In a word, the scene of the painting gives as little to the non-scene of photography as possible; ‘I always had a passion for painting’ is the first sentence of L’instant decisif. 6) Even the little aspects of the systems are explained, because it occurs that, in a too French manner, the bipolarity becomes a ‘play of images’ like we say a ‘play of words’.

In any event, the compositional astonishment and its liaison with the ‘tukHè’ predestined the photographer to enter into foreign systems and to globalise their day-to-day appearance, and to create a considerable phenomenon: a photographic sociology of human groups. This occurs on three different levels: civilizations, nations, and places. A) The three prostitutes in Mexico (AP, 278) actualizing the Mexican constriction show us a civilization. B) The little girl in Sifnos for Greece (***CP, 154), Rome for Italy (CP, 150) show us nations, and C) 1963’s Chambord (CP, 151) illustrates a place in every strength of the term.

This structural and existential sociology supposed the transition of heavy cameras to the Leica, ‘to very small, easy to handle cameras, whose lenses were very luminous and whose grain was very fast, and which were developed for the needs of the cinema’. However, a mentality was also necessary. We are in the thirties. We have just seen that in America, Walker Evans is an archaeologist poet. In Europe, Mauss moves between sociology and anthropology. Malraux feels the shock of Asia. German National Socialism opposes races and continents and takes Oswald Spengler seriously. Hergé, breaking away with McCay’s fantasizing, takes on a veritable collection of the world through a clear narration cartoon, where Tintin the reporter extricates their sparkling objects in their diverse cultural areas.

Let us not forget that the ‘tukHè’ of twenties surrealism was a great training period for the ‘tukHè’ of the decisive instant-moment. Cartier-Bresson spoke of these first surrealist fervours with emotion. He recognized his debt towards filmmakers Eisenstein, Griffith, Dreyer, and Stroheim: ‘they taught me to see’, meaning to capture the ‘organic rhythm of forms’. There was no need for less than that rhythm to ensure the oblique déboulé of the composed grasping.

Henri Van Lier

A photographic history of photography

in Les Cahiers de la Photographie, 1992

List of abbreviations of common references:

AP: The Art of Photography, Yale University Press.

CP: Special issue of “Cahiers de Photographie” dedicated to the relevant photographer.

The acronyms (*), (**), (***) refer to the first, second, and third illustration of the chapters, respectively. Thus, the reference (*** AP, 417) must be interpreted as: “This refers to the third illustration of the chapter, and you will find a better reproduction, or a different one, with the necessary technical specifications, in The Art of Photography listed under number 417”.