PAUL STRAND (U.S., 1890-1976)

The positivity of the shadow

In photography, which Talbot defined as « the art of fixing a shadow », the shadow is merely a domestic. Its role is often second and serves as a background for light. In the best-case scenario, with Hill and Adamson or Margaret Cameron, the shadow shared the half-empty space with clarity in stained glass effects for the former, and figurality with the latter.

However, is there not a positivity of shadow? We saw Peter Henry Emerson practice it secretly, like the unanimous link of natural interrelations between beings (AP, 149-156). From 1900, at a time when Emerson ceases to occupy the front stage, it plays a declared role with two young photographers. Where Steichen seems to have been struck by the shadow’s capacity to derail the classic scene, Paul Strand was taken aback by its auroral availability. In the light of their theme, it is not surprising that they should both start with pictorialism, were linked to Stieglitz, and collaborated to “Camera Work” throughout its entire existence - from 1903 to 1917.

6A. The shadow and the non-scene: Steichen

Like Stieglitz, Steichen, who is fifteen years younger than the former, accompanies almost the entire history of photography in his era. He constantly offers a firm theory; from 1900, he produces revolutionary photographs. Very early on, he tries unified colour, then differentiated colour. He gives aerial photography a go during the First World War. In 1920, he seeks photographic equivalents to science, his aim being to suggest Einstein’s space-time. In 1923, he is appointed chief-photographer for press group Condé Nast (Vogue), and develops the multiple-source lighting system that will be embraced by fashion publications and advertising with the arrival of styling in 1930. During the Second World War, he will also give naval photography a try, while organizing about fifty significant exhibitions until “The Family of Man” in 1955, which suggested his talent for entering into the photographic subject of a hundred or so photographers from various horizons.

For this evolving activity, we must assume some great character qualities. However, Steichen also needed a photographic subject that would allow him to marry all others, or at least the greatest part. This subject is the non-scene. It is linked to photography for a series of question, particularly for the role played by invading and divagating shadows.

To measure the stakes, let us remember that WORLD 2, i.e. the grasping/construction by « wholes » made of integral parts (the mediaeval “partes integrantes”), had called upon the scene (the greek « skènè), a place where events and objects occurred in the distance, not too close, not too far, standing out like “forms” on a “background”. This gave way to the semi-circular Greek theatres. The words “theatron” and “theory” both find their roots in the word “theasthai”, which means looking from a totalisating view, in the fashion of a Euclidian geometer looking at a triangle. Photography, initiating WORLD 3, derails this “scenic” view, even provoking a cult of the non-scene.

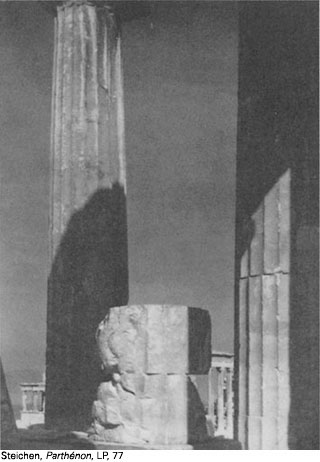

Steichen literally cultivates the non-scene by unbridling the invasions of the shadow. Talking of his 1901 Black Vase (BN, 174) he says: “It is one of these bizarre things that are nothing, that mean nothing, but to which it is impossible to deny a large measure of artistic sentiment. (…) But why should it be called Le Vase Noir instead of - in a more obvious way - the white window or the stretched neck?” In 1907, his view of Versailles (AP, 167) is almost a classic example. Indeed, he only keeps a light shining above the huge shadow over the escalier de l’Orangerie from the monument and gardens representing a masterpiece of classic architecture. His demonstration is even more exemplary in 1921’s Parthénon (*LP, 77). The latter is a “formal” building, so much so that it is regulated according to the golden number, but here reduced to two drums between two columns, also cut by a violent shadow/light chiasm, while only three of the Erechtheum caryatides can be distinguished in a faraway de-centring.

|

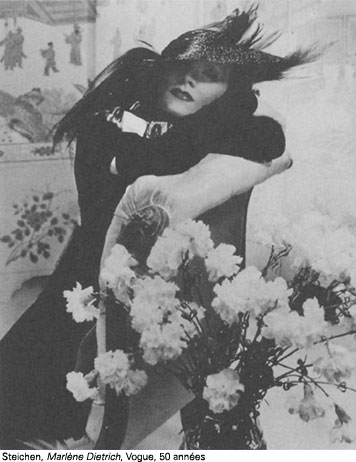

We have just spoken of demonstration, and it is true that Steichen is not only reflective but also reflexive. His Self-Portrait with Brush and Palette (BN, p. 172) dated 1901 is a meditation on the respective situations of painting and photography. In the beginning, everything happens as if the scene of scenes had to be fixed in a solid pictorial frame-index. Yet, the disparate shadows inherent to photography have dispersed brushes, palettes, collar, and part of a door, half-face in virtually unlinked locations and according to angles that have blown away the pictorial frame-index. A rhythm whose only correspondent is Jazz – hence of cubism which is in full bloom at the time – reigns. Through the multiple-source lighting, the jazz rhythm will find its place and will blossom in Marlène Dietrich’s 1932 ragtime (**Vogue, 50 Années, p. 12), which is not unrelated to Picasso’s Nu Couché, dated 1933. In 1920, Stravinsky had published his Ragtime.

One of Steichen’s – the practitioner and theoretician – most significant actions is the collection he assembled of aerial photographs shot during the First World War, often under his direction. He gave copies of these photographs to the New York Museum Of Modern Arts. There, we find all the philosophy of photography as an indicial phenomenon, one that is non-referential, barely indexed. After photographs of stars and galaxies, nothing better blows away the non-scene and the role played by shadow than a battlefield shot from the skies.

|

6B. The irradiation of shadow: Paul Strand

Ten years younger than Steichen, Paul Strand also participated to the pictorialism of « Camera Work ». He will work for a similar time span as Steichen, and will also envision the positivity of shade. However, what strikes him is not so much jazz-like eruptions, but the calm, the possibilities of inchoative openness, the within, towards the light without having reached the light yet. In that, he was possibly influenced by Peter Henry Emerson, who – in around 1885 – had seen the future calmness of shadow in the opposite sense, as a unanimistic deepening into a common root (AP, 149-156). Or simply, he belongs to this era that was sensitive to initial tinuities, for many, like Proust, Atget, Debussy… Simultaneously, shadow bears an elevation of the literal sense towards spirituality. Anagogic.

His inchoation and anagogy probably explain that Paul Strand is one of the rare photographers to make photographs that will arouse expectancy. A bit like a page of a cartoon. Not for the suspense or the potential accumulated energy or the trans-mutational metastability. To the contrary, he leaves the show to its maximal placidity, with the least indexation, like Atget and Proust, with an aim that the becoming should come from the impressed surface as such, from the infinitesimal (in the contemporary Valery sense of “already your nuance varies”) nuance devoid of functional destination.

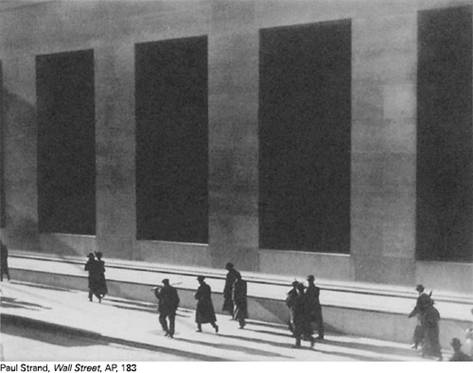

One day in 1915, the large, high windows of Wall Street “make”, an evening, or rather, a morning (***AP, 183), not through the light that falls upon them, but through the shadow which has already begun to irradiate an intimate and secret beginning. Thirty years later, we will meet Suzan Thompson (AP, 192) who is standing perfectly still, just like the Church on a Hill, Vermont (AP, 190). In 1967, a couple of Romanian Peasants expresses a future that we cannot guess (AP, 196).

|

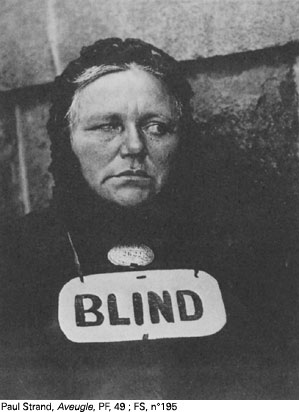

One perfect moment of this vision-construction will be his wife Rebecca (FS, 208) in 1923. Her essence lies in the simple lying head, to which two lifted arms are firmly stuck, multiplying between her and them the awakening shadows, the underarm uncovered blending in this birth in her hair, allusively pointing at the bottom part of the image. We could also find 1916’s The Blind more archetypical. Made in the photographer’s early days, we sense that he felt that the light was merely a tiny and faraway birth in an immense shadow (****PP 49; FS 195).

Of course, such a taste for nativity and inchoation had to pursue the path of abstraction already walked by Malevitch and Kandinsky in painting. In the last issue of “Camera Work” dated 1917, Paul Strand published two photographs. One shows a palisade (PP, Camera Work, 59), and the other, under some beams, shows the pure image of the two great natural statutes of shade: being the background of objects, being the projection of objects. The difference laid in the fact that in Strand’s work, the shade was the place of engendering, not the light.

Strand was a Jew tormented by his spiritual options. He underwent a violent conversion in 1932, moving from Stieglitz’s aesthetic movement to the ethic movement of a convinced socialism. He was sufficiently militant to incur the wrath of McCarthyism, and was forced to travel. Did this moral conversion lead to a photographical conversion? In no way. The analogy of shade had no reason not to get along with the social becoming. In fact, here, the photographic subject and the social intention bounced from one to the other. The authors of On the Art of Fixing a Shadow judiciously highlighted 1916’s The Blind (***, 195) and Chair Abstract (196), a working drawing dated the same year.

There could be an exception: the blazing gaze of the Young Boy photographed in 1951 in the Charente (AP, 194). Yet, looking at it closely, if there is a psychology, it also moves from the equal spreading of shadows, in gestation of the light.

|

Henri Van Lier

A photographic history of photography

in Les Cahiers de la Photographie, 1992

List of abbreviations of common references:

AP: The Art of Photography, Yale University Press.

FS: On the Art of Fixing a Shadow, Art Institute of Chicago.

BN: Beaumont Newhall, Photography: Essays and Images, Museum of Modem Art.

LP: Szarkowski, Looking at Photographs, Museum of Modem Art.

PP: Photo Poche,Centre National de la Photographie, Paris.

The acronyms (*), (**), (***) refer to the first, second, and third illustration of the chapters, respectively. Thus, the reference (*** AP, 417) must be interpreted as: “This refers to the third illustration of the chapter, and you will find a better reproduction, or a different one, with the necessary technical specifications, in The Art of Photography listed under number 417”.