Visually, it is the structure of things "space" that is important.

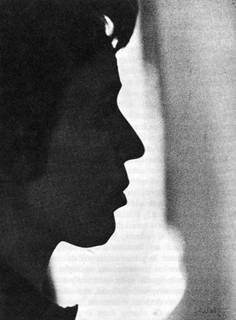

Cartier-Bresson, Photograph n° 144.

One can find in photographic prints - possibly indicial and possibly indexed - the three principle orders that organize the realm of signs. Photographs show particular denotations (the neighbor's dog or the murderer's revolver) as well as general denotations (desolate, cool, luxurious, etc environs). They also show connotations, that is to say frames of mind, social or epistemological prejudices of the person shooting the photograph or the (ironic, militant, neutral, aristocratic, populist, bourgeois, Muslim, Jewish, German) mentality of the intended addressee. Often one can find marks of the following type: a flowery tree branch on the foreground is indicative of the genre of the postcard or poster, with its specific denotations and connotations. In any case, regardless of whether or not the photograph is figurative, there are almost always and sporadically at the very least, field effects.

|

As the latter aspect is little-known, let us first focus on field effects within the domain of signs. When Michelangelo sculpts a body with one thigh clearly shorter than the other, we do not perceive a deformed body in a congruent space, but a congruent body within a curved space. When Tintoretto inserts three incompatible planes into a painting according to a given perspective, it is again the word curvature that best approximates the compatibilization between these calculated heterogeneities effected by our brain. This also applies to texts. Writings that are now regarded as classics are in fact those in which the same curvatures take place, i.e. curvatures of sounds and rhythms, of paradoxically contrary logical structures, of divergent types of images, and in general of all these instances at the same time. Great moments in music and dance are illustrative of the same compatibilities of incompatibles. In all of these cases we can speak of field effects, which are sometimes semiotic or indicial, often motorial, and which are always perceptual. These field effects are decidedly not connotations, nor even secondary denotations, nor messages in the proper sense since these all would have to be specific at all times while being absolutely general. Rather, they are "visions", "points of view," or fundamental modes of capturing space-time consisting of rates (of aperture-closure, suppleness-rigidity, compactness-porosity, continuity-discontinuity, volume-shifts, envelopment-juxtaposition, etc) specific to each individual through which not only Rabelais, Beethoven or Picasso are almost always directly recognizable, but also the majority of individuals, as evidenced in graphology, which studies these field effects in writing. This is an everyday experience, even though western theory remains habitually blind to it. As Dostoevsky noted, certain people do not attract or repel us through particular messages or social status, but through inflections.

In addition, field effects traverse indices, and especially photographic indices. In the photograph, patches of light and shade, of fullness and voids; the convections of noise and organization, as well as the paradoxical disparity between denotations and connotations force the eye and the brain into compatibilizations through curvatures and educe general rates of opening-closure, density-porosity, expansion-contraction, etc.

However, from this point of view there is a difference between signs and indices, at least in the west. In its textual and iconic practice, the technological mindset of the west has become so infatuated with denotations and connotations that it often ignores - in practice and almost always in theory - perceptual field effects, except in the case of radical artists, in whose work they are essential. In short, one could say that field effects are intense and rare in western productions. Yet the opposite holds for even western photography, where field effects are not very intense as the photographic aleatory does not allow their multiplication or complete insertion. On the contrary, due to the same aleatory character, the field effects are scattered everywhere. It is precisely in photographs indexed to the highest degree in terms of denotations and connotations that the contingencies of the spectacle, and in any case those of the impregnating photons, often effect the strange curvatures and perceptual, indicial and semiotic inflections of the singular rates of aperture-closure, opacity-porosity, continuity-discontinuity, and so on, in the creases of a dress or a jacket, or in the encounter of the bride's bouquet with the top hat of her witness. And this does not even presuppose true indices, which are denotatively and connotatively too revealing, as field effects are often triggered most successfully in those areas of the imprint below the level of the index, thus very close to the background noise.

This brings us back to the differentiation between frame-index and frame-limit. Undoubtedly, denotations, connotations and field effects can be obtained or put to the fore through a judicious frame-index. But one should not forget that the frame-limit, as pure limit, has its own efficacy. Every experienced photographer knows the following exercise: one puts one's eye into the viewfinder, and then slowly moves the latter haphazardly over the environment, at first generally without anything happening, and before long quickly and suddenly, without there being any additional movement promising anything more substantial, it then tightens, curves, bends lightly and constructs compatibilities out of incompatibles. Through the effects of the borders and angles of the frame-limit, denotations and connotations are activated above all when these are embedded within local and sometimes general, perceptual field effects. This entails that one can distinguish two main types of photographs. On the one hand, there are those photographs in which the frame-index and its rhetoric is dominant while subordinating both the frame-limit and the aleatory, as can be seen in family, advertising, industrial, and pornographic photographs for instance. On the other hand, there are those photos where the frame-limit "the mobile frame " is the predominant factor, thus dispensing with the evident rhetoric of the frame-index. This not only concerns photographs taken partially or entirely at random, but also those one usually associates with the so-called masters of photography. Perhaps it would be better to call the latter photographers tout court, as, rightly or wrongly, they remain close to the spontaneity of the photographic process.

|

Harvard College Observatory,

1853.

|

Therefore, a photograph is a space of incessant triggering. There, denotations, connotations and especially (perceptual, motorial, semiotic, indicial) field effects are set off most vividly and elusively, the one passing continuously into the other as everything is in overlap and only in problematic emergence from an initial magma. Benefiting from the superficiality of field and framing in particular, indexations can render these triggers outspokenly centripetal, as is the case in advertising, pornographic, industrial or family photography. But it is necessary to acknowledge that the spontaneous triggering of photographic capture is ordinarily more centrifugal, thereby largely escaping delimitations.

Labyrinths were paths almost always without exits. Photographs can lead to anywhere but lack paths.

Henri Van Lier