LOCAL ANTHROPOGENIES - PHYLOGENESIS

PRIORITY OF TECHNIQUE ( Le nouvel âge 1962 )

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PRIORITY OF TECHNIQUE (Le nouvel âge 1962)

Originally, this study was entitled Le Nouvel Age, Technique, Science, Art, Ethics, 1962. The

current title aims at better marking the omnipresent and preliminary role of

Technique in the human phylogenesis. The English translation also bears a new

title: Priority of Technique (The New Age, 1962).

The technical object strongly fashions culture. Men, women, and children see it,

touch it, and manipulate it. It penetrates the human body with its rhythms and

configures it as much as it is configured by it. It unceasingly intervenes

between man and nature, between man and man, and it would not be an easy task

to demonstrate how so many sublime theories are only ever its reflection. It

plays a role in every civilization, not just in a few, such as science. It

concerns every class of a society, not only the elite, as art does. It is

thereby logical that we should start with it.

* * * About this book * * *

The main concern of this paper is to attempt an assessment of one of the most brilliant and comprehensive syntheses, that advanced by Henri Van Lier in his book entitled "The New Age", 1962. It is a significant essay presenting an intellectually inspiring and invigorating integration of technology, science, art and ethics, viewed in the perspective of an all-embracing, philosophical vision of culture. It is one of the most symptomatic expressions of the quest for ideological and philosophical orientation to be found in contemporary Western thought. Further, it is a synthesis of a special kind, for it is worked out as if the march is simultaneously "in progress" and at the crossroads. Janusz Kuczynski. C. 1990

Published in : The International Society for Metaphysics. Studies in Methaphysics, volume I, Person and Nature.

Published in : The International Society for Metaphysics. Studies in Methaphysics, volume I, Person and Nature.

* * *

INTRODUCTION

A. Omnipresence of technique

Indeed, we cannot doubt that Homo – standing apart from all other beings through his angular and angularising articulations and by his flat hands in bilateral symmetry – should be a technician from instant to instant. In the phylogenesis, Homo erectus developed techniques one million years before he practiced somewhat detailed languages. In its ontogenesis, each hominoid specimen swims in a technician environment from its cradle or the arms of his genitors. Our languages only have significance insofar as they are the phonic or written thematisations of a preliminary technical milieu. Although they have forgotten it, 'classic' linguistics from Saussure to Chomsky very well described the formal properties of languages, but were unable to understand that it matters. For Homo, even 'Nature' is made technical. Paths cross his forests. He ritually hunts or rears his animals.

We have noted that angularising techniques prolong Homo's angular body hence increasing its powers, sometimes disproportionately. Yet, there is something more essential. Techniques introduce and support the own spaces and times of each people, hence its topology, cybernetic, logico-semiotic, its presentivity, what we call its culture or its civilization. The absence of the wheel comforted the constrictive and future-less cultures of Amerindians. At the oppostive, their constrictive and future-less grasping dictated that they should not invent the wheel.

The technique is so much the first and the last for Homo that he usually conceives the entire Universe as a technical object to which he elects a master Technician: the Gods, a unique demiurge, general fluxes, or still, a great Axiom. To such an extent that we may ask ourselves whether the origin of many of Homo's metaphysic problems does not lie in that he is incapable of conceiving anything but a technical object, whereas the Universe, which produced him as a technician, is not a technical object, but precisely a natural object. Creare, make grow, is the active tense of crescere, growing. Technician Homo was quicker to understand creare than crescere.

B. Absence of theories of the technique

Since technique is so important to Homo, we could have expected that it should trigger multiple and rich philosophies. Such is not the case. Not Plato, not Plotinus, not Saint Thomas Aquinas, not Descartes, not Kant, not Hegel, not even Marx elaborated philosophies of the technique. There is nothing in Confucius or Lao-tze in China, or in Çankara or Ramanuya in India. In the end, Aristotle is the only one who, because he enjoyed seeing things from the bottom up, stopped before 'technical objects' at the same time as he stopped before 'animal parts' (De partibus animalium). And the result was the famous theory of the four causes: to technically produce an object – for instance a Greek vase – we need an aim (final cause), a matter (material cause), a form (formal cause), and a producing agent (efficient cause). To these causes, the Medieval added the instrumental cause (a potters' wheel, a chisel, and a hammer). In their vision, we see that the final cause – which is the first and the last – is the 'most noble', the one that justifies all others. It is that cause that means that, for the Greek and the Romans, the Mediterranean Universe was a Cosmos-Mundis (non-vile), of which Homo is the Microcosm.

With the planetary success of western physics and techniques, the Aristotelian theory of the four causes became the model for all causalities, human or divine. Jehovah himself shares this model with the bartender, the surgeon, and the theologian. This Efficient Cause created Adam by sculpting, in the matter (alluvium), a form whose final cause was 'to his image and resemblance'.

C. First awakenings

In summary, we had to wait until the 1930's and Mumford's 'Technique and civilization' before it was stated that every civilization and culture were above and foremost a question of technique. Hence, the invention of the 'chase' of the clockmaking wheels in the late Middle Ages inaugurated relatively exact and constant timetables that allowed the West to move from maritime coastal navigation to the crossing of oceans, then from the Workshop to the Manufacture, to the Arsenal, the Factory, the Industry, triggering simultaneously Convents and Nation States. Until the day Homo discovered a 'being-of-the-temporal world', Heidegger's 1927 Dasein of Sein und Zeit.

It was only in 1957 that Gilbert Simondon, a young French doctoral candidate, dared a decidedly philosophical title: Du mode d'existence des objets techniques. Yes, indeed, technical objects had a 'practical' but also an 'existential' scope. Until then, there had been 'Histories of the technique' and 'Museums of the technique', but they went no further than juxtaposing descriptions and dating machines and processes. Simondon's revolutionary work went largely unnoticed. Was it deemed too technical for philosophers, and too philosophical for technicians? Or was it simply too unsettling… Just think! Technical objects, the slaves of our daily lives, would concern, condition, and carry the secret perception that we have of our existences! Whereas existentialism had only just suggested that existing (sistere, ex, being projected towards) is the ultimate framework of human destiny and freedom.

Yet, in 1959, the author of the present Anthropogénie found the Du Mode d'existence des objets techniques. He had only just published Les Arts de l'Espace, where painting, sculpture, architecture, and the fine arts were understood as being the produce of particular technical gestures; gestures capable of constructing and maintaining the space-times of groups or individuals like ordinary technical gestures, but also to thematize these space-times, and even to grant them a statute of absolute (solvere, ab, untying from any local and transitory operativity) by boosting or neutralizing them. Since the work focused on the arts of space, the thematized and absolutised space-times were called 'pictorial subject', 'sculptural subject', or still, 'architectural subject', so many 'work subjects' that had a sense per se, independently from the descriptive or narrative themes that they conveyed. Among the work subjects, da Vinci's Mona Lisa, Michelangelo's David, Borromini's Chiesa were a 'Vinci', a 'Michelangelo', a 'Borromini' before being a Mona Lisa, a David or a Roman Chiesa. In Africa, the statue of a king, an antelope or a monkey were, through the work subject, 'Kuba', or 'Luba', and 'Bambara' or 'Dogon' before being a king, an antelope or a monkey… even though they were that too, politically and ritually.

During the sixties, Homo was decidedly moving from what the Anthropogénie calls WORLD 2 – the world of the 'distant continuous' of Greece and the West – to WORLD 3, the world of contemporary 'discontinuous'. This violent turn was obviously caused by new Sciences, new Arts, and new Ethics, but also and more initially by the mutation of the Technique. Indeed, the latter was moving from 'energy machines' that had ruled since the origins of Homo to 'information machines' whose theory had begun being explained with the Theory of information and the 1948 Cybernetic. This abrupt turn was dramatized by two world wars, inchoatively (inchoativement) in 1914-18 and decisively in 1940-45.

Thereby, Le Nouvel Age is the sum of the Les Arts de l'espace and Du mode d'existence des objets techniques. The three chapters of the present work on science, art, and ethics were preceded by a chapter on technique that was as considerable as the three former put together. In October 1963, Gilbert Simondon, who was putting the finishing touches to L'individu et sa genèse physico-biologique, published in 1964, wrote the following lines to the author (who chose the italics), which are enlightening as to the three works: 'I admire the strength of the ideas, the richness of the documentation, and this unity, this power of integration that makes your book the testimony of a way of thinking that has its own logic, its own axiomatic capable of accounting for the modes of realities that are just appearing through the process of technical inventions. Furthermore, this work possesses a true aesthetic strength that is capable of creating a link, of instituting a communication under a sort of activity of the imaginative oversimplicity'. In this context, the term 'aesthetic' assuredly meant a grasping of things that, in the space-times of human productions – hence in their topology, cybernetic, logico-semiotic and presentivity – perceives their existential implications and instaurations, whether relating to daily objects, scientific theories, works of art, political or religious protocols, traditions, etc.

Perhaps because of this 'generalised aesthetic' (the work of another author bore the same title at the time) 1962's Nouvel Age had much more scope than the two works – albeit remarkable – of Gilbert Simondon. Poland's Academy of sciences, which was then trying to open soviet Marxism to modernity (and in particular to phenomenology) hurriedly translated it into polish, Nowy Wiek, adding a preface that had socio-political undertones, which the original did not have. In Canada, in 1962, the same year as the Nouvel Age, Mc Luhan strongly brought focus on the Technique through his genius shortcut: 'The medium is the message'. In the latter, he thrusts forward, in just five words, that the technical structures of a media (radio, television, etc) were in itself a message (existential) more fundamental than the particular messages that it conveyed. Hence, he felt that he could make a distinction between 'hot' media (radio) from 'cold' media (television). Prime Minister Trudeau heard of the Nouvel Age from Jean Lemoyne, his adviser. He decided to give the author all the necessary means, including television teams, to organize an international seminar on the theme 'Technique and its cultural implications'.

What interests us here is not that the author jumped at the opportunity. Perhaps his penchant for a 'generalized aesthetic' already led him towards 1965's L'Intention sexuelle', and to his 1970 reflections on Industrial design. What is remarkable is that no one cared to take over a project for an international seminar on Technique, which was ready. When in 1990, the Société internationale de Métaphysique – regrouping forty or so countries – dedicated, in its first volume Person and Nature, a long chapter to Technique under the signature of Janusz Kuczynski, it almost exclusively used the Nouvel Age as reference.

D. A few reasons behind this negligence

What is behind this repression and even this foreclusion of technique in human ontologies and epistemologies? The theme alone would deserve multiple doctorates. We shall make do with a few ideas.

(a) When Homo, this living bio-techno-semiotic, creates the first systems of his Cosmos-World, he goes immediately to the signs, even to the most elevated signs: stars. He does this using a mixture of astrology and astronomy that we encounter in Egypt and in Sumer, but also on the other side of the world, with the Australian aboriginals. Then, he becomes more rational during the 'axial period' (Jaspers), in the era around – 500, when he turns to more or less mathematical abstractions, such as Pythagorean figures, Platonist figures, organic topologies of Aristotle's eternal species, mutual conversions (Yi) of the Yin and the Yang, Quick (thick universal blood) of the Amerindian, Good and Evil of Manichaeism. As if the sublime alone was capable of justifying Homo. As though remarking on some of the techniques, too contingent or too heavily material (guè-ôdès, said Plato), would have compromised its justification as a culminating species.

(b) Homo has always attributed properties of revelation, lucidity, and almost divine demonstration to his languages. However, we humiliate this illusion if we recognize that language relations ('in languages there are only differences' Saussure) are only the specifications and thematisations of the technical relations that they are satisfied with suspending (putting in between parentheses) the operating dimension.

(c) Technique is not only a means, it is also a milieu. A milieu is largely independent from what it encompasses; there are unforeseeable developments, it dominates more than it serves. Recognizing the status of Technique's 'milieu' in human reality means recognizing its modesty. We could think that, in order for this humility to be bearable, we had to wait for the sixties when Homo started realizing that the Evolution is in no way orthogenetic, but luxurious. That it is not a constant growth towards him, as Spencer and Bergson thought around 1900 and Teilhardt de Chardin in 1950; and that – to use the words of Stephen Jay Gould – he was only a 'punctuated balance' amongst others.

(e) We shall not forget simply epistemological reasons. Indeed, what Homo calls his ideas, his concepts and his axioms chiefly depend on the cortical areas of his brain, characterised by their speed and determination. Hence, nothing is easier to do than speculate and build abstract systems. At the opposite, objects and technical processes largely depend from the deep brain, for instance the basic glands and the cerebral trunk, which have extremely performing autonomous memory as they allow a hairdresser or an airline pilot to remember the thousands of nuances in the handling of a pair of scissors or a joystick. Yet, these solid teachings are very slow to acquire and modify. Hence, abstract ideas are passed down from the master to his disciple, sometimes in a mere moment, where many years are necessary for a technical aptitude to be passed down from a master to his apprentice.

(f) Still epistemologically, the order of exhibition and the order of invention are not the same in technique and philosophy. Descartes is so convinced of playing with 'clear and distinct' ideas and Spinoza with 'adequate ideas', that they both believe they can describe an order of exhibition equivalent to their order of invention. And they write 'discourses on the method', 'rules for the direction of the mind', the 'ethic demonstrated in a geometric manner'. Their rational pretension can be found in some English empiricism. Yet, such an illusion is not possible for a technician. Simondon insists that, in Watt's invention of the steam machine, the crossroads between theory and empery are so numerous, so inextricable, particularly between preliminary analogical invention and posterior digital rectification, that a discourse of the technical method is not probable. The Eiffel Tower is a popular example of the part played by day-to-day working operations in the construction-invention of technical objects.

(g) Finally, Homo's trust and defiance towards the Technique has an ontological source. We must recall that the primordial articulation in the Universe is the distinction: functioning / presence (s). (Anth. Gén. Chapter 8), and that everywhere we find in Homo his favour for experiments of presence that put the functioning in between parenthesis: music, spatial arts, religious rites, orgasm, all the banal forms of daily drunkenness, nirvana, dikr, voodoo… (Maslow noted all these peak experiences among students from one same University that had all been deemed 'normal' by their peers). They are all different forms of functioning being put in between parenthesis, sometimes by neutralizing, other times by boosting their perceptive-motor and logico-semiotic field effects in the comptabilisation of uncoordinables that is rhythm with its eight resources (ibidem).

However, technique stands on the side of functioning, and the word 'rhythm' only designates the regularity of cadences. Hence, Homo admires technique, he develops it, and in turn, each morning it gives him his immediate goals. But it is always a bit as though it was a preliminary or a fundament in view of something else that would solely be truly essential, the 'final cause', when for example working for leisure. Buddha leaves the 'technical' management of a kingdom to seek the silence of the without breadth (nir-vana) where functioning are abolished. A Japanese general director suddenly leaves the huge factory that he has spent his entire life building to go and watch cherry trees in blossom. It is as though technique, as respectable as it may be, was never the last word, but always ended up as a means, a game of ends and means. This happens even when it questions the infinite spaces around the big bang to attempt touching, sensing the Last Word, the Ultimate Question, which are supposed to be of another nature.

Thereby philosophers – who are convinced in advance that technique is not final – would have ended up forgetting just how foremost it is, how constantly primary. The Anthropogénie is not a philosophy. It deals with origins, genesis, 'genius', and takes into consideration the ultimate goals, but starting with their preliminaries. Especially when these preliminaries, such as Technique, can be more or less neutralized, boosted by 'presentive' behaviours favouring pure presence, but that are never outdated or forgotten.

(h) We still need to specify that the Technique has not always had the same importance in Homo's phylogenesis. Despite its powerful ascent from the Palaeolithic to the Neolithic, the primary empires, and the Greek and Roman rational crafts, it did not shake up Nature much; and this, since the day circa 1000, when Western Homo did not see Christ return and decided not only to obey Nature, but also to exploit it by becoming an engineer, a co-creator alongside the Creator Engineer. Energy machines created local perturbations while the incommensurably more powerful forces of nature soon re-established the compromised ecological balance. Economic and political systems held on to the illusion that they governed the world. In 1948 still, in the Human Rights Declaration, States proclaimed that they were 'sovereign'.

This changed with the reign of information machines that begun soon after the Second World War. The expertise of energy machines was slow to pass down, but the know-how of information machines is rapidly decipherable and understandable. In the same time, it is globally transmitted through the development of the communications it generates. In fifty years, the couple energy-information modified the ecological balance of the entire Planet, meaning its climates and living species. Today, technician Homo has many of the properties of the omnipresent Engineer that he used to think as being the Demiurge of his Universe. In 2007, he hopes that, in 2008, he will be able to recreate several conditions of the big bang at the CERN. These urgencies further take him away from any philosophy of the Technique, or the opportunity to daydream in increasingly rarer moments of pure respite.

Chapter 1 - THE THREE FACES OF THE MACHINE

By approaching the history of the technique, the sociologist has the satisfaction of finding the same steps, whatever the envisaged viewpoint may be. Whether he is interested in the machine for its great types of functioning, its political or artistic incidence, or for the optimism or pessimism it triggered, the sociologist must always consider these three eras: what comes before the industrial revolution, the industrial revolution itself, and finally, our era. We will obviously discuss precise dates and we will ask what facts rather than others decided of the beginning and of the scope of the great eras. However, the global articulations remain. Mumford gave us a classic expression by making the distinction between an ecotechnical era right until the mid 18th century, a paleotechnical era covering the 19th and early 20th centuries, and a neotechnical era, which we inaugurate. [1].

We shall not escape a similar division. Perhaps the most substantial progress of this reflection is to stop talking of the machine in general and to distinguish three stages, three violently contrasted faces, which triggered very different cultural reactions. We cannot go straight to the last, ours, because its predecessors still inspire our optimist or pessimistic philosophies as they do our daily options, which may be irritated or fascinated by it. Furthermore, the most advanced stages of a technique still include the first as elements: the rooftop is still held in place by the floors.

Hence, we must turn to the past in the aim of genetically grasping the articulations, the stratifications of today's machines, and our emotional reactions to them. In pretentious terms, our research aims to be not historical but phenomenological and structural, as befits a coming of a reflected culture.

1A. THE STATIC MACHINE

Paleontology dates the arrival of man and his tools. Needles and combs made from bones, hatchets and arrows made of flint prove more, in man's eyes, than the shape and volume of a skull. Indeed, the means of transformation – whose internal and external relations show very well that their functions were grasped as such, as a 'secondary' universe; the technique – is capable in turn of being transformed and developed. Koehler's monkey, when deciding to grasp a stick to reach a banana, invents a transitory tool, which in this case is not one. The true tool stabilizes itself, detaches itself, and refers to other complementary artifices and to its own development. It supposes a power of symbolization, of objectivation, of distance that is typical to man. The way in which its idea implies the notion of system invites to put its development in relation with that of the system per se: language [2].

What were the first machine-related principles put to use? From the Palaeolithic, rupestre representations of traps demonstrate how the animal, when touching the bottom, would cause the fall of bevelled tree trunks. The principle of the lever was working. Yet, the true beginning of the machine starts with the wheel during the Neolithic era. In the interlocking of the disk and the axis, the wheel brought a richer application of the conjugated functions and supplied the first Antiquity for its peak. Lever and wheel, with their derivatives, the pulley, the hoist, the gear and the turning machine, – all engines for the reduction of forces – would suffice to carry, in war time and in peace, the agrarian cultivations of the Nile, the Euphrates, the Ganges and the Yellow River.

The classic Antiquity and the first middle Ages did not require much more. For social and religious reasons [3], the Ancients were not so much engineers as they were astronomers and physicists, and the mechanical poverty of their hourglasses and their clepsydras contrasts with the mathematical refinement of their sundials. Even their vocabulary is disappointing: the Greek Mèchanè and Latin Machina refer to the aspect of cleverness, surprise, and abrupt efficiency of the engines rather than to their mechanical characteristics of independence and automacity [4]. If Ctesibius invents a force pump and if Hero of Alexandria uses the pressure of heated air and water, it is essentially to combine automatons for playful or cultural means. There is only one area where antique technicians considered their talent with some seriousness: war machinery and in particular torsion catapults where they transformed the teachings of Philo of Byzantium, of Vitruvius and of Hero of Alexandria into empiric recipes. For the rest, the Romans used Archimedes' bucket drains for the evacuation of water in their mines. They developed the norias and, on the eve of Christianity, watermills. Yet, these remarkable inventions do not bring about the technical revolution that they could have. Even in the area of architecture where they had the merit of perfecting the grouting process, we see that the citizens of the empire continue using the costly solution of inclined plane aqueducts, whereas in Pergamon, the principles of communicating vessels were in place as soon as the second century of our era. It is true that technical knowledge is not solely cumulative; it supposes a mind that decides to exploit it or to let it go to waste. Schuhl speaks of the 'premecanician mentality', or the 'antimecanician mentality' of the Antiquity [5].

Around the fatidic year 1000, Western civilisation will deeply change this attitude. If, until then, the technique aimed at ends without much considering the means, it is because it had its slaves, a weak motor force that was expensive to feed, albeit mobile. The fall of the Empire and the progressive reflection on the implications of Christianity will soon put an end to this resource. Henceforth, the first aim of the technique will be – even before the pursuit of the result – to lighten the burden of man and the effect was that it greatly favoured the results and the West then launches into a prodigious research and exploitation of exterior forces. The strength of the animal in the hardware and the harness; physical forces in the endless development of hydraulic wheels, the windmills of Islam, the sails of ships. The forces of regulation in the fixed steer and the pedal loom, chemical forces in gunpowder and particularly in the distillation of sulphuric and nitric acids, the aggregates of metalwork, all this leading to the use of light, iodine supports: colourless glass, the milieu of chemical reactions, and paper, soon conjoined to mobile characters and the printers' press [6].

Yet, these conquests, which take place between the 10th and the 13th centuries, almost fade before another contemporary conquest [7], the mechanical clock. The event is one of history's most considerable, where Spengler sees the symbol of a new culture, as the regular chiming and the hand on the dial demonstrate an obsession for the exact and efficient length that was unknown to the Chinese, the Indians and the Greek and that penetrates all our creations. Munford dates the 'geotechnical' era from this invention and underlines the fact that the clock, engendered by the monasteries' need for regularity, were about to provide the western man with this abstract, rigid framework that was independent from the seasons and that would lead him to conceive the past as such (let us recall the historical resurrections of the Renaissance, Classicism and Romanticism), to place himself rigorously into space (let us look at the compass, the sailing compass, cartography, territorial explorations) and to be interested in pure greatnesses and powers (the elements of capitalism), and finally, to engender these concentrates of precision, regularity, synchronisation, and acceleration: our machines.

From a machine-related viewpoint, escapement is not a simple progress, but it is a mutation. Nothing in the triggering of the bow or the catapult or in the rhythmic swaying of the noria can forecast the idea of this oscillation, which alternatively holds and frees the movement [8] . Henceforth, the new mechanic mind is born. From now on, it will be possible to envisage the indefinite repetition of an identical action using a winding system. It will be possible to combine a succession of different actions in advance: in its germ, the clock contains not only the perpetual Strasbourg calendar, but all the automatons that will characterise the Swiss clock making of the 17th and 18th centuries. And if all this gratuitous virtuosity was looked down upon, let us recall that the process, in the form of the jumper, feeds Pascal's arithmetic machine and that the cam, which belongs to the same mind, is at the source of all our modelling engines.

Such was in substance the technique from its origins to the 1750's. Indeed, the great scientific discoveries of the Renaissance and the Baroque only produced some industrial applications much later. We can see its culmination in 18th century navigation. Seeing the position of their colonies, the Portuguese and the Spanish would sail along the coasts to reach the latitude of the targeted country, and would then follow the parallel calculated by the angular height of the Polar star using a process that was already known by the Greek. Because of their rivalry, and because their colonies were in high latitudes where the parallel makes a noticeable detour, the French and the English launched into a severe competition to achieve a navigation in straight line that demanded the delicate calculation of longitudes. They needed either chronometers or optical instruments whose refinement used turning and dividing machines, the ancestors of every tooling. Armed with these precious clocking precisions, redoubtable artillery and prodigious sailing force, a vessel of the admiralty of Louis XVI summarises the ancient technique [9].

Had the machine remained at that mechanical stage where it only transmitted movements either directly or indirectly [10], it would not have caused a problem, and we do not see how the philosophers of the time would have felt it to be much of a concern. They had only conceived it as it was, as every other tool or utensil, an artificial object that was by essence the opposite of living or mineral beings, an object that had a somewhat particular causality, one that Aristotle called instrumental. They did not give it much consideration, as they did not much consider anything that was related to practical realisation or manual work, which were not worth a free man. It was nothing for them to be concerned with [11]What was a pulley, a hoist, a catapult, a ram, or even a clock or a pump, if not the prolonged gesture of a limb similar to our limbs, similar to an arm that coils, empties, balances, turns, to the hand that buckles, grasps, lets go in rhythm? And it is indeed the image of the accrued body that is most often alleged by theoreticians. In fact, the almost exclusively used material was wood. It is the most docile and the closest material to the human body (whilst steel with the violence of the miner and the blacksmith) [12] was still the exception. As for the windmills and sailing boats, if they did anything else than prolong a gesture, they also captured the most familiar elements very visibly. Orators, poets, decorators and liturgists had there, during thousands of years, an endless arsenal of images that were reassuring and understood by all. The natural character is so particular to these forms of energy that it explains both its quality and its flaw: a very high turnover contrasting with the wastefulness of steam engines and the irregularities linked to the whims of the seasons.

The teaching mode reinforced cosmic sympathy: the latter, which was intuitive, consisted in the acquisition of dexterity. Things were supposed to conceal mysterious powers that the artisan would free in an intimate contact that resembled a taming. The modeller tested the clay with the palm of his hand and the peasant knew the earth and the rain in a touch that spread to his entire body.

The interposition of the tool and the machine did not change much. These instruments of contacts participated to the proximity of the worker's gesture. Hence the initiatory character of the teaching both with the primitives and in our corporations, which conclude the testimony of the ancient machine by binding man to society and nature. Dexterity supposed the direct and daily commerce of the master, from whom the 'mastery' was passed down in a kind of filiation. Similar work relations engendered generally stable and warm social structures despite inequalities. We only note one revolution since the Antiquity, which was quite content to submit to the order of the world until the Renaissance, impatient to exploit it. For Francis Bacon, the technique was 'mankind added to nature', and does not include the merest idea of violence, at the opposite of Descartes' perception. In their opinion, we act upon it – more in desire than in actions – by acting like it, according to a formula used by Marsile Ficin.

This image will seem idyllic for the end of that period. New industries – mining, glass, and printing – owe much to capitalism, which was quick to subtract them from the social rules of the corporation. On the other hand, it is in musketry that appeared, for the very first time, the advantages of mass production that engendered collusion between technique and militarism that meant that campaigning armies and an industry ready for wartime became the ideal of many technicians. Finally, the beneficial growth of the demand depended of (through the bourgeois luxury) the great courtesans [13]. Yet, these doubtful alliances concern more the atmosphere favourable to the eotechnical object than itself and do not compromise the reassuring picture that we have painted. Capitalism, militarism and luxury of the court all introduced flaw while they maintained a considerable cultural meaning, as the urbanistic realisations of the 17th century testify.

When the great encyclopaedia is published around 1700, it is both the conclusion and the apotheosis of this era [14]. We shall not waste a minute in saying that it already announced – in more than one aspect – the new age. It inaugurated the scientific comprehension of the machine by enlightening the laws of mechanic set up by Galilee, Descartes, Leibniz, Newton, and therefore went beyond the fortuitous and non-communicable skills of earlier technicians. But it is one of these exceptional moments when humanity slides from one phase to another by conjugating benefits and by neutralising the drawbacks one by one. The machine is scientific. Yet, it remains intuitive. It does not abolish dexterity. Rather, it explains it and makes it transparent, joining body and reason. This wonderful, precarious balance culminates in the fifteen volumes of plates that all speak to the mind, the eye, and to the gesture while conjoining the virtues of the number, which will be the world to come – unbeknownst to Da Vinci – with the simultaneous grasping of the outlook that Da Vinci – the perfect Renascent – had exhaled as the supreme fruition. All this remains at the level of man, right to the appearance: the machine looks like a piece of furniture in the house, unless that, windmill for the miller, it is the house itself… Furthermore, in its illustrative aspect, what is the Encyclopaedia if not the ideal workshop where all the machines would have gathered in a closed order, at hand's reach, in the semi-mental form of printing?

However, we must repeat that it is a transition. By penetrating the science machine, it exposed it to become the instrument of an abstract production that would escape man's measure. Simultaneously, it took away the initiatory character from the teaching and put it at the reach of anyone capable of providing an effort. It shook up every corporative privilege and the entire ancient regime. Therefore, the Encyclopaedia is a direct prelude to the Industrial Revolution and to the French Revolution. It concludes the first age of the machine as it opens the second.

1B. THE DYNAMIC MACHINE

No one agrees as to the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution. At one time, it was fashionable to see it as one of the consequences of the Napoleonic wars that stimulated discovery and – through the national armies and their complex logics – placed Western Europe in a state of industrialisation. Uneasy with this unflattering thesis for humanity, pacifist historians such as John U. Nef underlined to the contrary that the dices had been thrown as soon as 1785 and that it was more appropriate to invoke the exceptional era of peace of the 18th century, first attempt of a united Europe [15]. Indeed, the Industrial Revolution has distant ancestors in both war and peace. Its most characteristic engines – the steam machine, the coal high furnace, the automatic loom – are the result of hundreds of individual inventions whose path can be traced back to the 17th century, the Renaissance, and even before. And we know that capitalism –the luxuries of the court and the militarist regime –, which would favour the industrial mentality, had former credentials. For we must understand that this Revolution was as much a general climate as a machine-related effervescence. If the need for a good turnover steam machine is increasingly pressing in 18th century England, it is because important commercial problems increasingly faced the spinners who were overwhelmed by the demand of the weavers, or affected the weavers that could not follow the orders of the spinners. This alternative was exasperated by a strange law that suppressed – for some time – all the taxes on Indian cottons and silks in an aim to deliberately whip up English textile. Therefore, the Industrial Revolution appears like a confluent where the technique (steel puddling in 1783), the economy (suppression of the last privileges of the corporations and extension of the markets under the influence of Smith's liberalism), external (the Indian colonies) and internal policies (exodus of English peasants towards the cities under the pressure of gentlemen-farmers), all of which were animated by what we really ought to call the new mentality [16], où and in which Calvinist fervour played a great part [17].

Regardless of its era and causes, the machine shows a new face circa 1800. It ceases to be an innocent means to somewhat lighten human tasks and ensure – against all odds – a day-to-day subsistence, and it starts appearing like an indefinite power instrument aimed at satisfying equally indefinite needs. We can pinpoint this mutation with the passage from the Newcomen machine to Watt's machine. With the Newcomen, the effect of steam was to push back the piston, then pushed by the atmospheric pressure. The work depended of a – naturally limited – natural force, the weight of air. We were still in the world of wind and water mills. Watt turns the problem around. Henceforth, the steam will push, assuming engine time, and, as its power can indefinitely be increased, it is also indefinitely multipliable [18]. Consequently, the commands are passed from nature to man. Energetism – which will soon be developed by thermodynamic and electro dynamism – is born. It will find a powerful ally in an old principle that takes a new departure at its contact: organisation. And the machine that – since its origins – had not alerted men of culture, started to inspire a moral, almost a religion: the religion of efficiency, quality, result, and progress, through the brutal force of the steam machine, and through the organised force of the loom or the telephone. Having conjugated these two grandeurs, the railway became the masterpiece of the era.

There were the optimists who promised a universal statute to steam, and soon to electricity and petrol. Marx could well see that these new engines alienated the proletariat, that they favoured the 'degrading division of work'. However, in his eyes, it was a transitory inconvenient that was essentially linked to the power of capitalism. To see better days, it would be enough to knock capitalism over and to give the worker possession of his work tools. Someone like Berthelot was more confident still when he considered that the new instruments applicable to the chemical synthesis that he promoted would not only fill the material needs of the human being but would inevitably engender (through overabundance) a political regime that would ensure happiness and virtue. He was constructing the economy of a revolution where Marx saw a stepping-stone that was everywhere necessary.

Yet, the vast majority of men of culture were sombre as they felt that the disadvantages of what they were beginning to call the modern world were tied to its very being. There was the long complaint of the poets, from Vigny to Rilke, going through the furore of Nietzsche. Flaubert attempted to grasp the century and proved that it was possible to raise to the style the ancient Carthage or Alexandria, or even the more traditional province of Madame Bovary, but not what there was – both in intuitions and things – that was purely 19th century. Indeed, the failure of the Education Sentimentale preludes that of naturalism. Painters, who were more radical, decided to silence a world that they did not understand; the workshops of the Renaissance stepped in Dürer's paintings, and the windmills of the 17th century in Rembrandt's. The locomotive, despite Turner's first enthusiasm, only became pictorial through the fog of impressionism [19]. However, architects and engineers had great confidence in steel and concrete, although they usually used them to simply render characterless and ancient architecture bigger. This general state of helplessness is well expressed in the contradictions of the aestheticians of the era who float between the bare truth of true functionalism, indigent seeing the elementarily of the machine of the era, and the untruth of the ornament that will result in the Modern Style. Yokes are supported by Corinthian columns or hidden behind tapestries [20]. Ruskin is probably logical when he preaches the fleeing of a world he sees as degraded and a return to nature, the source of life. His opinion is shared by less aesthetic moralists. In the myth of Erewhon, in 1872, Butler, who supposes that the machines obey to Darwin's natural selection and that they have arrived to hound man, offers the lone salvaging measure: their destruction.

Assuredly, we find many prejudices and ignorance in these viewpoints. But then again, a condemnation that is so unanimous and that persists for such a long time undoubtedly aims further than the political flaws denounced by Marx. It had to be linked to the deep character of these new objects. To express the uneasiness, was it enough to say that Pittsburgh's environment of smoke, dust and sludge would place the rich boss in a situation that was almost as gloomy as his starved workers? That, for the very first time in history, an entire civilisation rested on the mine, the most inhumane and backward of industries. That the cult of production demanded that everyone show a contention that would engender the down to earth small mindedness of Victorian morals and a barbarian conception of school, ensuring training but also the depersonalising discipline required by the new jobs [21] ?

The explanation is all too simple. In this regard, countries are very different, and Germany never knew the monstrous excesses of England [22]. Furthermore, hideousness characterises the dynamic machine in the couple coal-steel of its beginnings, but fades away in the couple electricity-aluminium in 1850 and in the couple petrol-special metals from 1880. Electrical apparel invites cleanliness, finesse, and geometry. Electricity, which is easily transportable in every corner of the workshop or the region, suggests industrial decentralisation by freeing the machines from the propeller shaft of the steam machine [23]. Petrol has the same effect and, as it allows the automobile, it frees the town centres, saturated by the fatal convergence of railway lines. Does all this not plead in favour of a frank, clean life? Munford was so convinced of this that, after Lenin, he saw the possibility of a new era in electrification, petrol and the telephone, a 'neotechnical era' that would relay the 'paleotechnical' era of coal and steel under the condition that men should draw the economic and political consequences of these new powers. Under the angle of ugliness, dirt and fatigue, the flaws of the dynamic machine would seem to be correctible and not linked to its very being. However, the critics were not satisfied with so little. They did not lean their essential argumentation on the ugliness and brutalities or the social injustices. Contrary to the opinion of Munford, they deemed that a complete passage to electricity – if it were at all possible – would not solve the problem. What is the problem, if we try to go back to before these clumsy, passionate formulations?

1B1. The dynamic energy machine

The 19th century energetic machine is in complete break with man and nature. The mechanical machine that preceded it prolonged the human body and natural forces: mills, sailing boats, and even pumps and presses captured wind and water according to their own output, putting them to work without disguise, using them on site [24]. At the opposite, the locomotive, the high furnace, the electrical turbine and the internal combustion engine not only isolate the worker but also, instead of blending in with natural forces, stir them in every possible way. They transmute them from a form into another, whether it is mechanical, thermal, electrical, or chemical. In this context, the concept of energy and the principle of its consecration will be discovered, transporting them everywhere without any reminder of their origin. Hence the feeling – that some witnesses expressed – of finding oneself before a new being that, even when it was not as frightening as the first high furnaces or guilty of rape as the factory and the railway that violated the landscape, remained inassimilable through the culture and value systems, because we only knew of man, of nature and of the few objects binding the two. After the semi-artificial engines of the past, the energetic machine is a consumed artifice that forms a strange reign, away from everything.

Furthermore, a means only seems natural to us when it is visibly linked to a concrete end: grinding wheat, lifting a stone at the top of a wall, or dyeing a garment. This was the case of the mechanical machine whose energy was polyvalent by right (it could be used for a thousand things) but was in fact limited to a task to which it was no longer 'dedicated'. The energetic machine severs this link. Its end is no longer the accomplishment of a concrete action but to produce energy in general. It is a means to a means. It inaugurates the reign of the pure means, which is as distant from man as it is from nature, as strange – some will say monstrous – as the reign of the pure artifice.

On top of its strangeness, it also has something that is aggressive for the living. Whilst it changes its mind, adapts ever-renewed operations and works through synthesis and continuity, it goes straight ahead, endlessly repeating the same action, analysing its processes thoroughly. This was tolerated in the slow ticking of the clock and the mill, reminiscent of vital rhythms, but in the hundredfold speed of concentrations of energy, it shows a scary face, the face of raw matter. The linear thrust, the numeric multiplication, the analytical fragmentation are the very characters of materiality. Under the effect of acceleration, they take a relief, a purity that comes from the to-and-fro of the piston, of the rod and the wheel, the vertiginous antipode of life. The deep shame is that such blindness is often more efficient than its flexibility. The living felt dispossessed.

The only thing the living could do was to force himself to adopt the invader's way of being. We shall not dwell on chain work that gives the gesture a stereospecificity where man models himself on the machine, where man 'serves' the machine in countdown instrumentation. It is a consequence that is inscribed in the logic of the energy but it is one that perhaps does not belong to its essence. By right, it also tends to reduce the tasks of the labourer. The influence on the intelligence of the user, the worker, and even the inventor was much more fundamental. Indeed, the energy machine does not belong to the lived experience of the ancient dexterity, nor does it belong to a true scientific knowledge. There is nothing scandalous there, we shall say, because, between the non criticised function of empiric and the critical fact of science, there is room for a third order: that of the criticised function, which belongs to modern technique [25]. But precisely, in the dynamist world, the function reduced to itself (the means of a means) is so poor, so material, that it was never able to define its own territory in the kingdom of knowledge. We observe that most of the technicians of the era hesitated between the status of empirical finders, and that – less glorious – of the simple appliers of scholarly theories. To this, we must attribute (more than to a pretend modesty or incapability of expression) that 19th century technicians found themselves in trade-related problems and hated going into any general idea of the technique, except to affirm a thoughtless faith in quantitative progress or, more often, to situate themselves outside of culture, (in their eyes) the territory of the philosopher, the literary, the artist, and recently, the man of science [26].

In turn, this state of things affected social relations. Assuredly, it is difficult to set apart the abuse of capitalism as criticised by Marx and the crimes of the energy machine. Yet, the classes engendered by economic structures were soon joined by three other classes, which were equally 'alienating'. The businessman uses it to economic or political ends, in a manner that is particularly arbitrary that it does not have any intrinsic finality. It is therefore questioned by this arbitrary itself and by his ignorance towards the instruments on which he leans and that he must content with exploiting. The technician, engineer or foreman understands his instruments – although he feels that he is a scholarly bastard – but in return he is excluded from the decision of the ends, extrinsic to the machine and under the responsibility of the businessman or the politician. Finally, the worker, simple working livestock, is excluded from the true comprehension of the machine apart from that of the pursued objective. The proof that these characters are linked to the energetic mechanic statute is that we find them in Stalinian Russia, where the arbitrary of the businessman – the planner – is illustrated by what the Russian critics have since baptized 'economic subjectivism', the uneasiness of the technician through the drama of the intelligentsia, the functioning livestock of the work camps [27]. The social disarray is best found in the era's architectural dispersion. Apart from a few policing-inspired urban attempts like Haussmann's in Paris, never has the space of the house, the city, or the road been more incoherent than in the 19th century.

Finally, the adversaries of the dynamist machine deemed it harmful right down to its cultural advantages. One by one, they rejected the three arguments brought forth by its rare defenders, in particularly American technocrats of the 1920's [28]. You say that the machine increases leisure? But speaking of the sort means accepting a dichotomy where true life is nowhere, not in the work, not preparatory to leisure, nor in the leisure, which, deprived of articulations around work, empties of substance. It frees work from sordid constraints and, with the developments of electricity and special metals, goes as far as to dress it with an aesthetic order and functionality. To humanize a work, it is not enough to lighten it, but it must be made significant. Yet, the aesthetic of the styling, if reduced to the finish of the matter, to the round of the form and to a certain reminiscence of living being as invoked by Mumford, does not promise anything more than a vain rest for the eyes. There is little to expect from the functionality if the function of the means-to-means is devoid of spiritual content. The energy machine comprises the suppression of rarity [29] hence privileges and social classes. To the contrary, we have just seen that it implicates a new division in classes – the class of the businessman, the technician, and the executer – that is even more alienating than its predecessor. Whichever way we look at it, we are at the wheel…

1B2. The dynamic order machine

The technical world does not only have energy machines. It needs machine that produce forms, arrangements that are more spatial than in modelling machines [30], that are more temporal in the information machines. The 19th century was wealthy in both genres. It perfected the loom, mechanised printing, the sower and the reaper. It was revolutionary by creating the telegraph, the telephone, the cinema, and the radio.

Still, in its information machines, the technical world only saw a new means to activate its modelling machines from a distance. In these machines, it only saw an indirect way to favour his production of energy even more. It did not perceive the technical originality of information, which is that it can speculate over time and manage actions in return. It did not grasp the originality of order as a universal, physical and technical principle that is distinct from energy. In every way, it remains energetic. It is hardly surprising that here too it was open to reproaches. In its technical use of machines of order, we find everywhere the acceleration of linear movements that are recurrent, analytic, the means-of-means, the dependency of man to his tool.

Yet, what can be said of the manner in which the late 19th century and the early 20th century used the press, the phonograph, the cinema, the radio – and very soon, television – to multiply directly cultural realities, the text, the voice, the music, and the gesture? Was it not bringing to the life of the mind – apart from a democratic broadcast – the intense and varied exchanges that sociologists have always considered as its main engine? Even here the critics did not give in. Culture is an artifice, they say. Its end is to put us in contact with the real. Yet, the proliferating information screens both mind and things, and in this sense, it is passive. Not that it would provoke somnolence, but the activity that it triggers mainly targets the substitutes of reality, images, sounds, words, and phantasms that all too soon become ghosts [31]. Let us not prejudge anything. Perhaps that one day soon we will have to admit that, transported in another context, broadcasting takes on an unexpected character of truth. But then, it will no longer be simply quantitative multiplications.

In fact, the common trait of dynamic engines – whether of order or of energy – was clearly expressed by the Bergsonian philosophy that concludes the period: they are abstract [32]. The metamorphosed energy is an abstraction; it is torn away from its natural milieu and has become means-of-means. It is an abstraction that the repetition and the stereotyped succession made purely numerical through the effect of acceleration. Training, which is neither truly intuitive nor truly scientific, in the same way as the attached economic-social and urban relationships, is an abstraction. Information, which turns on itself, screening the world instead of revealing it, is an abstraction. Bergson does not explicitly draft the theory of the dynamic machines, but we can sense that these machines shape his environment when he opposes quantity to quality, the 'all done' to the 'doing', determinism to freedom, inert time to lived length. If he wants to reign, man needs these servants that will reduce him to slavery [33], Hence, it is essential that he should promote and control them, seeking in their gathering a 'supplement of soul'.

These analysis and those of the innumerable pessimistic essayists that follow [34], are still very much alive because the dynamic machine – like the static machine before – is a constant of the technician world, and its ideal of purely quantitative efficiency will exert its fascination over some minds for a very long time still. Bergson's sole mistake (and particularly his successors') is that he extended his criticism of one state of the machine to the machine in general. Not only did he and his followers lose sight that it could be subject to a metamorphosis, but they also forgot that it had known, in its origins, a much less redoubtable status. Yet, how could they think about that as they were submerged under new machines?

If we are more careful and if we look more closely, we shall see that, before the Industrial Revolution, technical objects had a very different status. We will understand that we must distinguish these two ages because we are inaugurating a third age, one that directly controls our future.

1C. THE DIALECTIC MACHINE

We are witnessing what is commonly accepted as a second Industrial Revolution. Yet, we still need to determine what it lies in. We are generally content with stressing that nuclear forces have given our energy machines a prodigious leap and that our information machines have gone from the still elementary stage of the telephone to that of calculators and cybernetic engines. And we can effortlessly demonstrate a huge increase of both power and precision: support before the oil and coal layers ran out (something that haunted the consciousness of the 19th century), mobility allowing for the improvement of deserted regions and decentralisation of the others [35]; perfection of the settings that increase the qualities of the finish and the proportion that Mumford saw in electrical apparels. But if things were to stay still from our cultural viewpoint, would we be much better off? In such a perspective, technique remains accountable for every accusation of anti-humanism accumulated against the dynamic machine, which remains suspect even in its advantages.

Thankfully, it is the place for a deeper mutation. Gilbert Simondon remarked that every technical object is engaged in a concretisation process, meaning that in the start, it is articulated in isolated functions and organs that are analytically distinct and that it tends to conjoin them, establishing concomitances, interrelations, and synergies between them [36]. But then, it is plausible that some objects present such a rate of abstraction that they appear and are known as abstract despite their concreteness whilst others present such a rate of concreteness that they appear and are said to be concrete in spite of their abstraction. We should like to characterise the present machine-related change using a similar mutation of rates. Whilst the 19th century machine (which was still analytical, linear and juxtaposed) seemed globally abstract and deserved every reproach that have since stuck to abstraction, our machine, in an ever-increasing number of cases, discovers enough synergies for concreteness to move to the forefront, taking with it a deep change of its cultural sense. We even feel that with this new face, it explains – or in any event reinforces – most of the essential characters of the contemporary world; that it suggests a value system susceptible of promoting a new humanism.

Hence defined, dating the second Industrial Revolution is no easier task than defining a date for the first. An energetic scheme as concrete as the Diesel goes back to 1893-97; a concrete cybernetic scheme like feedback also begins with Watt in the 18th century. However, let us not forget that far from the first trace of a technical discovery is its cultural glow. It has to become a daily object. Using other words, it must be industrialised. It is increasingly important that is should no longer offer a simple fact but a principle with its own fecundities. Therefore, as soon as 1780, Watt equipped his steam engine with a ball-type governor. When the machine turned without gripping, the balls were lifted by the centrifuge force and acted on a lever that would partly interrupt the entry of steam. Assuredly, such a device offers an example of retroactive action where an effect (the movement of the piston) acts on its cause (the entry of steam) to regulate it. There we have the feedback that we are so proud of! But it is completely different to invent a device enforcing a principle than laying down the principle itself. So Watt does not invent the feedback, he invents a mechanism that includes a feedback. We shall have to wait until 1868 for Maxwell to analyse this rigorously. Then, we will have to wait many more years before physiologists clearly recognise a structure of our nervous assembling. Then, we wait for some more until finally, with our contemporary cyberneticists, the feedback takes on the dignity of a universal scheme of functioning. Still, before truly being part of humanism, the man of culture must see the invention, and he will transform it into common categories. We can see that the road is long. It is even longer when some steps are skipped. Diesel, when he creates the spark-ignition engine, immediately made a reasoned invention by taking away its principle [37]. Some rare humanists have now understood that it concerns them.

When we consider these precisions, we can affirm that the concrete thought was rearing its head in the early 20th century when the First World War triggered a gigantic comeback of the most dynamist mentality. This comeback proved to be destructive during the conflict and constructive after it, and incurred the sad consequences that we know in the great crisis of 1930, which demonstrated the impasses of pure dynamism and would have perhaps been enough to promote the synergic preoccupations that were put aside, as we see in the American technocracy. In any event, the latter were brought to the front of the scene by a new worldwide conflict with its brutal clearings and need for instantaneous riposte demanding the dazzling progress of the radar, anti-air cannons, and operational research. The world took a new face that it held onto during peacetime. In short, the concrete mentality definitely joins the definition of cybernetic with the team of Norbert Wiener in 1948 [38], for information machines, and in the aforementioned thoughts of Simondon in 1958 for energy machines.

1C1. The dialectic energy machine

The concreteness or synergies of our engines are applicable to them all and demonstrate their unity. However, since some are more obvious in energy machines and others in information machines, we shall classify them between these two types for an easier comprehension.

1C1a. Synergy of functions

The body of an airplane must respond to at least three requirements: it must be rigid, offer a decent surface of sustentation, and break the air effortlessly. The early apparels dating back to the early 20th century had a carcass conferring them rigidity and a coating granting them the surface of sustentation. Yet, this distinction between the coating and the carcass imposed a weight and an angular form that were not compatible with breaking the air. In today's airplanes, the coating is streamlined in such a way that it is self-carrying, as the pressures that exert in one plan reel at the average curve, so much so that it can decrease the work of the carcass, sometimes even suppress it. Simultaneously, it improves its surface of sustentation and makes the breaking of air easier, since self-carrying, aerodynamic forms are ideal in this regard. Hence, we are here in the presence of three functions, once of which, the coating, accomplishes a good part of the two others, i.e. sustentation and breaking. We should even note that, by accomplishing them almost on its own – hence largely suppressing the antagonism that systematically occurs between two distinct organs – it perfects them. This is a case of simple versatility, which we will call a first-degree synergy.

Yet, some are more complex. The cylinder and the yoke of an internal combustion or combustion engine must provide a rigid volume that resists to the internal pressures. On the other hand, they must evacuate the heat provoked by these pressures. In the old engines, both functions were designed separately. The thickening of the cylinder and the yoke ensured rigidity, and a current of cold water dragging the heat ensured the cooling. Air-cooling is synergic. Along the cylinder – and particularly in the region of the valves – the cooling blades intervene, ensuring the thermal dissipation. Yet, when they are properly spread out, they also guarantee the rigidity of the volume, which used to be obtained by the thickening of the walls. These blades also work as support ribs. In return, their rib work allows making the wall of the cylinder thinner and also contributes to the thermal dissipation, which is already ensured by their blade role [39]. In the same way as with the coating of the airplane, these blade-ribs show us a function that accomplishes another by accomplishing itself: it is their simple versatility, or first-degree synergy. By accomplishing this second function, they perfect the first. We then speak of circular versatility or of second-degree synergy.

The physiology of our machines presents the same outline as their anatomy. In last century's internal combustion engine, the various operations are articulated in clearly distinct places and moments. First, the fuel is blended to the combustive air in the carburettor. Then, the hence carburetted mixture is introduced into the combustion chamber. Then, the spark plug lights under the action of an organ that is again distinct, the battery. Finally, the lighting of the spark plug provokes the deflagration of the carburetted mixture that activates the piston. In Diesel's internal combustion engine that opens the 20th century, these moments and places conjugate. It is indeed the injection of the combustible into the compressed air by the return of the piston that mixes it to the air (the role of the carburettor), lights it (role of the spark plug), and pushes back the piston (motor role of the deflagration). These are first-degree synergies. But we could find some second-degree synergies too. Whereas in the internal combustion engine there is a marked antagonism between the compression and the deflagration, since the latter – under the effect of the pressure – risks transforming itself into a detonation, in the Diesel, since the compression is the source of the deflagration, it reduces the antagonism between the deflagration and its effects that in turn provokes it. Thereby, it can increase itself by increasing it.

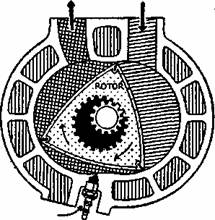

ÉCHAPPEMENT ADMISSION

BOUGIE |

Let us note that the progress of concreteness is not always rectilinear. In the recent Wankel engine, some synergies of the Diesel were abandoned. We go back to the spark plug ignition and to pre-carburation. There was still an antagonism between the properties of piston engines and turbines. The first run economically using petrol, and the easy transportation of the latter is well suited to the automobile, although they experience every loss of energy inherent to the brutal to-and-fro of the piston with its dual break. Turbines do not present these drawbacks, but only economically run using water or steam in reduced units, which, for the time being at least, makes them ill-suited for the automobile. Wankel [40] imagined a triangular rotor locked in a flattened cylinder. The three chambers created between the rotor and the cylinder serve the first to the admission and the initial compression of the carburetted mixture, the second for the maximal compression and its explosion, the third to its expansion and its evacuation. The revolution of the rotor that is provoked by the deflagration takes the carburetted mixture, compresses it, and accelerates its exhaust after its power stroke. Furthermore, it directly moves the axle, which is the soul of the fixed gear on which the rotor moves. Hence, Wankel designed a configuration of the piston that makes simultaneous and reconciles the formerly antagonistic functions of motor compression and expansion, and conjoins them both with a third function that used to be incompatible, the direct rotation of an axle.

The Wankel engine is a very good demonstration that it is artificial to consider separately the anatomy and the physiology of our engines since they are often in synergy among themselves. The classic airplane engine propels the aircraft as it spins the propeller. However, its body needed to conquer the air resistance in pure loss. The two functions of propulsion (physiological) and breaking (anatomical) were antagonist. The ramjet reconciles them: the air pressure at the entry of the divergent ensures, by compression, the combustion of the kerosene, whose gases lead to the propulsive effect by escaping the convergent.

It would be possible to lengthen the list of all these examples, particularly in electrical machine where, initially, enough precautions could not be taken to isolate the different organs from each other for fear that their fields should perturb each other. Rather than isolating the fields, the contemporary electrical or electronic machine attempts to conjugate them into one unique action. Simondon demonstrated all sorts of synergies that the passage of Crookes' tube into Coolidge's tube proposes in the production of x-rays, or in engines of amplification, that of Fleming's diode to Lee de Forest's triode, then to the tetrode and the pentode [41].

For the time being, we shall stick to a simple description, as this is not the place for underlining the cultural scope of all of this. Yet, if we remember the great distress that the machine caused in the dynamic era because of its opposition to life, we can easily imagine the scope of a transformation that, by reconciling what had previously been separated under the form of a context, gives it some characteristics of the human being, filled with first and second degree synergies. This kinship through the functioning goes way beyond the simple assimilation by appearances that is 'reminiscent' of life where Mumford already perceived a sensitive progress in 1934. Henceforth, on both sides, there is an organic idea, a prevalence of the whole over the part where the part is no longer simply a part but becomes an organ.

1C1b. Synergy of the machine and nature

In the same way as it isolated its functions to realise them with more purity, the 19th century machine worked on the exterior ambient nature: it transformed it as it avoided a transformation in return. The ancient locomotive rushed ahead, enduring resistance to air in pure loss, unwillingly. To propel the aircraft, airplane propellers would determine an acceleration of the air upstream that was wasted in turbulence.

Our fast cars improve the use of air resistance to improve their road holding. In a recent model of airplane, the Bréguet 941, a light coating of the synchronous propellers allow to uniformly steer, on the wings, the debit of the air accelerated to increase the lift. In both these cases, the first function of the machine (the propelling) provokes a reaction of milieu that, far from being damaging or vain as it used to be, favours another function in return (adherence or sustentation). The positive synergy no longer plays mechanical functions between the organs or the functions, but between the machine and its milieu.

Furthermore, we see in this order some synergies that we could define as being negative. Thanks to its versatility [42], the Guimbal generator can entirely be immersed with its turbine into the pressure pipeline of the barrage wall. Yet, if the liquid flux accelerates, it will also accelerate the propellers of the turbine, the effect of which is to heat up the latter, but also to increase its own turbulence, facilitating the evacuation of heat. The stream flow is taken in a mechanism where it is both a principle of heat and cold. It is no longer an action that increases another in order to grow itself. The problem is less linked to the increase than to the settings. The machine and the milieu are in circular causality of regulation.

We are a long way away from the dynamist rape, but are not back to the simple prolongation of natural forces characterising the static machine. Reconciliation occurs: it is an active reconciliation based on reciprocal causalities that gives birth to what Simondon calls an 'associated milieu' [43]. The water around the Guimbal turbine, the air around the fast car or between the propeller and the wing of the Bréguet 941 are not machines; nor are they simple nature; they form a median reality with the machine. This type of reality will only need to grow to become more spectacular – and we shall soon see some examples – for its cultural incidence, the fading away of the ancient, unmovable Nature, to become blatantly obvious.

1C1c. Synergy of the matter and the form

When Aristotle distinguished a 'matter' and a 'form' in every finished being, he took his inspiration from the technical objects lying around him. Any object or machine from yesteryear resulted from a configuration imprinted into a material. Whether it was an antique pulley or a 19th century steam engine, we could find everywhere a structure and a receptacle, and between the two lay the separation characterising abstract technique [44].

In front of our thermometers or our germanium transistors, it has become impossible to consider the germanium as in what the form of the instrument incarnates. It is itself what is most original in the form through the intimacy of its electronic structure. Similarly, the tungsten in the anticathode of a Coolidge tube is not simply placed in such a way as to allow x-rays; its high atomic number and its high resistance to fusion constitutes the fabric of the device and its idea. In our electronic engines, and in those that enforce nuclear energy [45], the 'material' and the 'formal' are conjugated and sometimes even go as far as exchanging their roles.

Let us apply the same observation to this other matter of a machine: the combustible. The form of yesterday's locomotive made do with using heat, whatever its origin, according to the exteriority of the abstraction. Hence, it burned just about anything and only chose coal by commodity. At the opposite, our rapid engines burn their combustible by introducing what is most particular into the most particular of their structure. They have become most exclusive in their choice, according to the demands of concreteness [46].

Can we say that matter and form are in synergy in all of these examples? Assuredly, and we were perhaps too quick in stating that they incorporated and merged. In reality, they figure distinct poles of tension insofar as the matter ceases to be pure passivity to take a machine-related originality in its fabric. They fecund one another: the function of the form accomplishes itself even better that it gives the matter an almost formal task and reciprocally; we find our second-degree positive synergies. As these interactions – in a nuclear reactor for instance – are regulating and stimulating, our negative synergies rear their heads here again.

Here again it is not a case of switching to humanist consequences. Yet, seeing the influence that the distinction between matter and form has had in philosophy and ancient rhetoric, seeing its role in the conception of nature as a permanent substrate and as man as simple modeller of things, we glimpse, once again at the cultural transformation implicated in the new motor schemes.

This too brief overview of energetic synergies shows where their interest lies rather well. They do not necessarily promise a decrease of the organs. The latter, in a Diesel engine or a triode, are more plentiful than in the most abstract and corresponding machines. Nor do they promise us that machines will be easier to understand or easier to repair, or even more polyvalent. The abstract machine, insofar as it separated the functions, was appropriate to the explanation. It was easily repairable and was apt to a wide variety of roles. But the concrete machine introduces a new world that, in its whole, is more powerful and flexible than the former.

From the viewpoint that concerns us, it particularly brings about a new mentality. There will probably always be a vast number – if not a majority – of static (there is no technical world without a hammer or a hoist) or dynamic (we will continue to juxtapose functions for economic, convenience or prestige reasons, as we can see in automobile accessories) tools and machines. There is probably no rupture between the most abstract machines of the 19th century and our more concrete machines, and the technical intention always encompassed a tendency to concretisation. Still, probably in the same way today as yesterday, every machine-related series must go through the most abstract, analytical stages, as we can see with the present nuclear related researches. But globally speaking, the technical world offers a new face. An increasing number of objects show a concreteness that is so stunning that the technician can perceive it as such, so that he may pursue it in an explicit manner, that from the point where he has to go back to abstract stages – like for his new series – he knows that this it what he tends to: this is the reason why he reaches it so quickly.

As we have just seen, synergy, taken in all its extension, is synonymous with organic relations between machine-related parts. It suggests dialectic relationships between machine and nature, matter and form. Hence, we shall not be surprised that the recent machine should introduce a new technical [47] and cultural view of things, or that it should favour it anyway. This is something that we shall verify in our information machines.