HELMUT NEWTON (Australia, 1920),

LENI RIEFENSTAHL (Germany, 1902)

The black of colour

For practical, printing reasons, we had to regroup the photographers who illustrate the virtualities of colour, even if this means that we are troubling the order of birthdates and if several of these photographers – particularly – worked in black and white. Perhaps that this regrouping is not too prejudicial since it shows just how colour defines another photographical world.

Animals have a vision that is adapted to their situation. A carnivore, as he must instantly hit his prey, could not be embarrassed with a thin discrimination of colours. On the other hand, fishes and birds may need it highly. Our primate eye seems to have been selected in the high tropical forest where our ancestors had to distinguish the fruits among the foliage and to reach them quickly. Hence, it perceives tens of thousands of colours, meaning of combinations between a hue, a luminance and a saturation. Simultaneously, it contributed to a differentiated social life, as there is probably a prettily circular causality between discriminatory primate vision and delousing. Furthermore, in the signed animal that man is, hence in an animal that seeks the ambiance but simultaneously feels isolated by the abstraction of the signs that make him up, colour plays a considerable affective role, warming and bringing the environment closer by its ‘warm’ hues, cooling it or taking it further away by its ‘cold’ hues. Apart from that, and independently from this affective comfort, the extreme variety of colours contributes to differentiate the topologies, cybernetics, even the logico-semiotics that our parties of existence represent, multiplying all sorts of ruptures, fusions, curves and inflexions.

Whilst painting uses thousands of colours, photography is rather coarse in that area. The number of hues is reduced, their delimitations are floating, and their impregnation on the film is slow. Let us even forget the fact that their conservation was hazardous for many years.

Colour photography then suffices to some practical missions, like deciding of the maturity of a harvest. Similarly, it is also adapted to simple affective use, for example for these amulets that family and identity photographs represent. It makes us forget the indicial aspect of every photograph, and favours the presence of the absent and even pure presence, as we find in Boltanski. Somewhat in the same trend, Walker Evans, in his later days, took great pleasure in going to the lost American high-plains to take colour photographs of architecture, as available to remembering that they were small. Of Time and Space, Christenberry’s title, demonstrates that in this case, time is more sensitive than space. Finally, colour photography shows the complex chemical reactions from which it results, which adds to its remembering aspect. The thing is particularly sensitive with the Polaroid, where the photographer-watcher attends the process when the image comes out, progressively, genetically.

However, for photographic subjects that required powerful perceptive-motor or logico-semiotic field effects, colour photography seems too poor, floating, and slow, as Cartier-Bresson wrote in 1952’s The decisive moment, before mentioning it again in his 1985 post-scriptum (CP, 20). The light of India – which is moist, blurry, con-penetrative and especially ‘slow’ – was the only one in which photographs could give Stieglitzian ‘equivalents’ in the work of Eliot Elisofon. As to the dye-transfer and Ciba chrome, which allow preventing the confusion of hues by saturating them, their unusualness is only appropriate in certain cases, for instance in Susan Meisela’s 1988 reportage in Nicaragua (AP, 429, 431) where the violent cut-out and contrast of the figures concords with the constrictive light of South America.

However, these last examples notify us that a combinations of deficiencies and forces triggers unforeseeable virtualities. As much as its capacities, the limitations of colour photography have stimulated new photographic subjects, whose reach was sometimes universal, and of which we shall explore a few striking examples.

27A. Ernst Haas or ghostly energy

In 1952, confirmed photographer Ernst Haas introduced a colour film in his Leica, opening a new world.

The easier to do at first is to follow him through the blurs. In his 1956 Bullfight (*Life, Colour, 147), we do not grasp the bull, the torero, nor do we get their reciprocal movements, but something like their polarity of energy, the essence of their fight. Since colour films are slow, every moving object gives a transparent image, says Haas. Transparent until it is blurred. Yet, this blur, to the contrary of the black and white blur is not fatally blurry, since it conveys coloured energy that, conjugated with it, creates a diffuse effervescence. The fight is not taking place somewhere, nor is it occurring at a moment, but what we have before our eyes is a Universe phenomenon. It is no longer an image corresponding to an external reality that would have been, but an image indirectly induced by faraway effects – due to the deficiencies of colour photography – a little like a particle is grasped through multiple compositions in a bubble room.

|

However, this grasping, which is both energetic and evanescent through indirect effects, no longer needs the blur. Because of the (fecund) deficiencies of colour, Haas is so happily settled in the fainting, transparency, bi-locations, ghostliness of things that not only do the famous pigeons of St Mark’s Square – which move – but the American roads and building – which do not move – become ghosts, tearing each other apart, fraying in the heavy, luminous curtain that delivers them to us. The Cowboys rentrant au crepuscule sur la prairie californienne dated 1958 (Life, Colour, 147) do they not come out of their milieu, but go back in it, losing themselves – dare we say die? In the last case very patently, since it is in the evening, but elsewhere the fraying of the vision gives a certain black of colour, which is somewhat opposite to the colour of black that we have encountered with Alvarez Bravo, Bill Brandt, and Eugene Smith.

To understand why this vertigo and coloured ghostization – which could have occurred before – entered photography in around 1950, we will repeat what we have said on Irving Penn, and the scientific, technical, industrial, computer revolutions of the era.

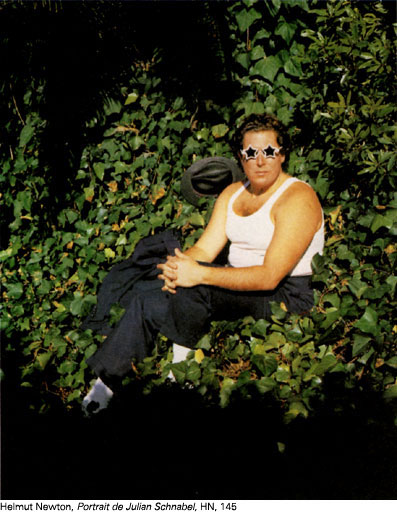

27B. Helmut Newton and crystallisation

Helmut Newton’s photographic subject is of a dense, contrasted, impenetrable, mineral, immobilizing black. With others, we regularly see white tearing black apart. With him, it is the opposite, black tears at the white. Among the Portraits, published by ‘Nathan Image’ in 1987, when we look at Grace Jones and Dolph dated 1985 (HN, 162), we see quite clearly that her black body tears, thunders, congeals his white body whilst his opaque shadow tears, thunders, congeals the white bricks of the wall at the back. This photographic subject finds an archetypal image in Bordighera Detail dated 1983 (AP, 449), where a feminine eye whose messy lashes are stuck into points by black mascara is frozen.

Therefore, why did we put the photographer of super-active black and white in our chapters on colour? Because he paradoxically confirms the ‘black’ of colour that Ernst Haas makes us sense.

1985’s Portrait of Julian Schnabel (**HN, 145) uses Newton’s typical scheme: the dark assaults the light but adapts it to the hugeness of Schnabel’s sculptural-pictorial universe. The essence is the two powerful jaws of shadow, one curving and encompassing from above, the other rectilinear and horizontal from below, both that bite at the clarity of the shining foliage, which is crystallographic and unforgivably proliferating, on which the painter-sculptor is seated. Then, in this general mechanism of the triumph of nature, everything seems to turn around for a little while, since right in the centre the fauna – the artist – explodes with the pink of his flesh, the pure white of his tee shirt, the whiter white of the frame of his spectacles. However, the last word goes to the dark, and the clarity of the character is drunk by the blue of the trousers and the jacket (hence confounded with the green of the grass), and pierced with the black stars of the lenses of the spectacles.

|

All this required an ‘equivalent’ to Schnabel’s plastic subject, this painter-sculptor who evoked The Sea using an immense panel of broken plates and The Voice of Callas by an upside down gush of colours rising and falling on a surface that is almost as big. Nature is not looked at from the outside, but from within its shadows and overlapping ivy. It is true. Yet, simultaneously, the ‘kitsch’ of the spectacles evacuates the naïve naturalism and demonstrates that the afternoon of a contemporary fauna merges nature and artifice, art and fake, stellar faraway and leafy close by, pop art and cosmological feeling of the ‘new image’. Colour photography only was capable of giving us such a blackness.

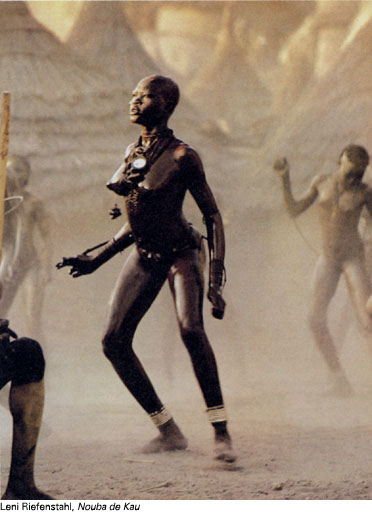

27C. Leni Riefenstahl and density

In her old days, the epic filmmaker who filmed Hitler’s apotheosis at the Nuremberg Rallye, then who photographed the 1936 Berlin Olympics (NV, 82) had to find with the Kau Nuba (published by ‘Chêne’ in 1976 (***), the outcome of her film and photographic subject, and therefore of her party of existence. A little before that, she had photographed the Nuba Masakin.

The Nuba is the people that (with the Japanese civilisation) most openly declared that man is a signed animal, also recognising this status not solely in a few isolated moments of their lives (like for instance in the course of exceptional ceremonies as the Rio Carnival) but by making the human existence into an immense ceremony, an almost incessant transformation of the male and female bodies into living sculptures, in a formidable adequacy of animality and signs, the Sign under its four modalities of indicia, indice, analogical referential signs and digital referential sign.

|

The encounter between Leni Riefenstahl and the Nuba was a culmination. Let us look at it closely. (A) On the one hand, a photographer whose film-photographic subject is close to Eisenstein’s and that never misses a volume pushed by its internal pressure, an increasing movement from the ground, a light engendered by the densities and shimmering of the bodies. (B) On the other hand, the ochre, dense earths of Africa, that dust or gleam on the young, shining, oily bodies. (C) The adequacy of the shining bodies and the Sign through the face and body paints whose artifice is exalted by the extreme and varied dissymmetry. (D) Finally, between the photographer and the glimmer of the show up to the rivers of blood in ritual combats, the intervention of colour photography with its slowness of inscribing, its mineralizing and here gleaming simplifications, its thicknesses of colours, its sliding towards black resulting from the often annulling meeting of coloured energies.

Poetic anthropology was missing in this history. Leni Riefenstahl, helped by colour photography, accomplished it. Particularly that in this case, a particular civilization, taking as its essential and almost-permanent theme the signature of the body, overwhelms local anthropology towards fundamental anthropology.

* © Ernst Haas / Magnum.

Henri Van Lier

A photographic history of photography

in Les Cahiers de la Photographie, 1992

List of abbreviations of common references:

AP: The Art of Photography, Yale University Press.

CP: Special issue of “Cahiers de Photographie” dedicated to the relevant photographer.

The acronyms (*), (**), (***) refer to the first, second, and third illustration of the chapters, respectively. Thus, the reference (*** AP, 417) must be interpreted as: “This refers to the third illustration of the chapter, and you will find a better reproduction, or a different one, with the necessary technical specifications, in The Art of Photography listed under number 417”.