SCIANNA (Italy, 1949)

The cosmological voyage

It is judicious to conclude this history of black and white photographers with travel photographs. The latter are as constant to photography as family pictures, which we have just considered with Boltanski. Here again, we had to wait until the seventies for this very ancient theme to give matter to photographic subjects, perhaps because, at the time, travelling drew all its strength in becoming cosmologic.

26A. Cosmologic space travel: Max Pam

As soon as 1850, the first photographers left for Greece, Palestine, Egypt, or simply for Central Europe, to bring back detailed and evident archaeological photographs. This was not really travelling. In 1893, Peter Henry Emerson’s On English Lagoons and 1907’s The North American Indian by Curtis show an attitude that is more anthropological than it is travelling. Assuredly, in the thirties, the reportages by Walker Evans, Cartier-Bresson and Robert Capa do include a notion of travel, but one that is very fleeting.

It is only in the 1970’s that Westerners started photographing other countries regularly and in large numbers, with an aim to participate to the lives of these countries, making this participation an ultimate goal. This sort of spiritual exercise consisted in entering, for a few weeks or a few months, in a value system that was radically opposite to theirs, in a cultural conversion that was voluntarily partial and temporary.

Why so late, and why Westerners? Perhaps because, to reach that point, three cultural mutations had to comfort each other. (A) That we reached the point of perceiving everyone and ourselves as states-moments of a universe in an irreversible, imprevisible and de-centrating evolution. (B) That – in particular – the revolution of species was understood – in this universe – as provoking new specific apparitions that were also irreversible. (C) That, after having believed in the universal man for around a century – with a peak during the Bauhaus – each felt the relativity of his own culture in a concrete manner, one that was not solely theoretical. Then, the true participative and mutative voyage became simultaneously attractive and redoubtable, sacred in the sense of Rudolf Otto. For nothing is more dangerous than truly participating to two civilizations at once. Like Victor Segalen, between China and France, had felt it as a poet as soon as 1920.

Photography is ambiguous for the peak experience (in the sense of Maslow) that the initiatory voyage represents. Because it offers the comfort of getting close to disorientation while neutralizing it: whilst one is busy setting a camera to ‘take’ an incineration in Nasik, one is distracted from the event. The too-disturbing present changes into a future (‘this will be developed and seen one day), that will offer a composed past (‘in Nasik, we saw an incineration’). At the same time, taking photographs may – if the operation follows a certain asceticism – provide the opportunity to receive full blast the aggression of the present, to hold it close, to radicalize it by not seeing it as unsettling or curious facts, but as a truly different space-time, that of another culture, hence of another world, behind facts. In a word, by grasping under the solely pictorial themes the matter of a true photographic subject, meaning a converting topology, cybernetic, logico-semiotic.

Max Pam intensely represents these participative, mutative, vertiginous travellers that made travel photography into an initiatory journey firstly for the photographer, and secondly for others. He is Australian, which means that he swims in Australia’s situation of behaviourist modernity. At the extreme spiritual opposite, he is confronted to Asia, and in Asia to India, which is perhaps even more disconcerting that Segalen’s China. He also travelled elsewhere. But to optimally grasp his practice of the great cultural split, we must follow him in India, and even in this distant region of the Ladakh, which was polyandrous at the time, and is still one of the highest regions of the world.

|

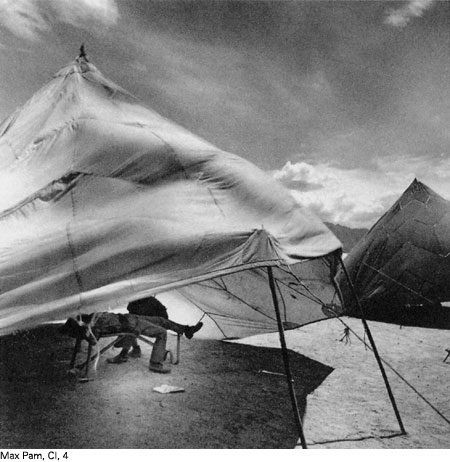

In the photograph we are discussing (*CI, 4), this military tent, the foot of the soldier sticking out, the mountain so high that, at the peak on which we are, we no longer see it, already make up quite a strong theme. However, it is in the photographic subject that the essence occurs. The frame is square. In this immobile square, the events circle according to the Indian circularity of the karma. The photo becomes a Tibetan mandala, a circle within a square, even a moving circle in the unmoving square. However, this would only be a symbol applied to the theme. To obtain the fulgurating mixture that this photograph represents, the circulation of the internal circle could not be closed as in a traditional mandala, but had to be irreversibly opened by the immeasurable distance between the very particular (the tent and the feet of the lying man) and the strictly immense (the mountain shying away) in a mandala, which is now active and exploded. The western world made Asian through the mandala. Asia becoming western by the opening of the mandala. Beyond every picturesque à la Salgado, and beyond every trivial psychology and sociology.

|

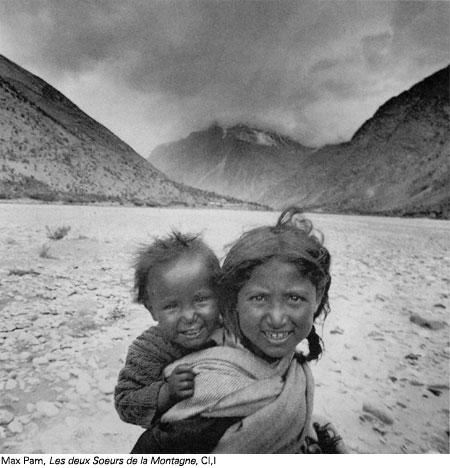

The Deux Sœurs de la Montagne (**CI, I) are more naively cosmological. The photo has kept only the extreme poles that are, on the one part, the two bodies at the centre of the forefront, and on the other part, the stone of the original mountain in its generative mist, in the background and the centre. Between the ancestral mountain and the actual children, the bed of the valley of stones runs frontally towards them and us, between two other mountains, two banks, the alluvial bed of the geological and cosmological process itself. The heads of the two sisters could have rejoined the original mountain, overstepping it. The photographer left, between them and the mother mountain, enough space for the filiation process to show us its millions of years.

Once again, the mandala of the framing turns clockwise through three mountains for two heads, two heads for one mountain, two springing up of heads for two depressions of the mountains. Once again, a movement triggers the explosion of the mandalian movement, which is lateral: the frontal movement of the process, opening a cosmos to a universe.

26B. Cosmologic voyage in time: Scianna

Scianna is born the same year as Max Pam. He also travels intensely, making photography an initiatory voyage to otherness. However, he travels in time, and the company is as dangerous, multicultural than space travel, since the epochs are as foreign and strange between them than places.

For this, there had to be a closed-in space, where moments of culture jostle each other until the unceasing time, like Sicily with its situation of central canal lock of the Mediterranean, its Empedoclean Etna, its cultural stratums crossed and coloured as the pieces of the legendary Pietraperzia apron.

For this vertigo to become photographical, it was an advantage of being a native of the island, but it was also good to have left it before returning regularly (as Nicolas Nixon would come back, in the same era, before the Brown Sisters) with an untiring amazement, encouraged by the photonic imprints that grasps what we seek and what we expect, but also what we do not see and do not expect. Particularly if, as shown in 1977’s The Sicilinas (LS, 38), this supposed a certain way of capturing the in-depth stratifications of space (LS, 80, 82, 87) capable of making the in-depth stratifications of time being felt (LS, 38). A serial vision towards the background exemplified by the stairs on the cover, and also in the manner that an innocent putto is folded in the unfolded slides of its volutes (***LS, 23).

|

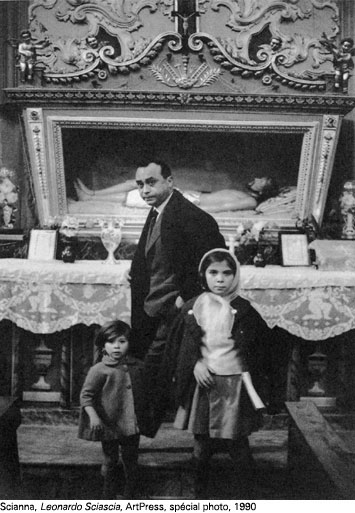

How can we resume, in one image, a photographic subject where everything is recurrence and comparison? The portrait of Leonardo Sciascia, dated 1967, could perhaps do (****ArtPress, special issue photo, 1990). The theme confronted two generations, the writer Sciascia and his children. The encounter had to occur in the church of Sciascia’s native village, Recalmuto. Moreover, it had to take place before a dead Christ to declare simultaneously the committed Christian writer and the Italian depth of time. Probably the mature Sciascia suggested a good part of the composition to the young, 18-year old photographer.

|

Yet, it is the eye of the latter that – at the end of the day – saw the triad of time so firmly (the past of the dead Christ, the future of the two children, the present of Sciascia) catch up in time through these triads of space: the past of the background, the future of the forefront, the present between the two. The past lies down, the future looks, the present walks; the past is transversal, the future faces, and the present is oblique, exploiting the spatial-temporal layering of the Italian Baroque that our putto warned us about. And by seeing how the horizontal whites of the cloth of the altar and the display cabinet of the Christ could be crossed by the white vertical of the little girl without loosing the stratum of the ages through the four heads.

During those 70’s, the initiatory and perilous voyage in the layers of time was not Scianna’s isolated invention. Around him, Italian designers were learning that, along with the universal technical demands inherited from the Bauhaus and updated by the ULM school, it was urgent to re-activate – through the contemporary utensil – some layers of the past, in what they would call the re-semantisation. It was not yet the post-modernism or the Transavantguardia italiana, but Italy, through its synchronic practice of two thousand years diachronic, has always felt – or anticipated – this sort of game with history.

* and ** © Max Pam / Métis.

*** and **** © Fernande Scianna / Magnum.

Henri Van Lier

A photographic history of photography

in Les Cahiers de la Photographie, 1992

List of abbreviations of common references:

CI: Caméra International, Paris.

The acronyms (*), (**), (***) refer to the first, second, and third illustration of the chapters, respectively. Thus, the reference (*** AP, 417) must be interpreted as: “This refers to the third illustration of the chapter, and you will find a better reproduction, or a different one, with the necessary technical specifications, in The Art of Photography listed under number 417”.