BOLTANSKI (France, 1944)

Transitionality and presence

All the photos before this were made to be flicked through, even when they were very dense. However, since photography became popular in the 1890’s, there has been another type of photographs, like those – isolated or jumbled up – in reduced or poster-format, reigning on the walls and furniture to guarantee a certain identity of the persons, families, and fluid groups: the photo-monuments. There are also those that nourished a personal theatre in an isolated drawer. These were usually violent or erotic, cabinets of curiosities and secret cabinets in reduction. If the kitsch of the 1900’s excels in these two genres, if ‘great’ photographers sometimes played a few scales on that side, very few made it their photographic subject.

However, this latency ended in around 1970. This was probably the result of the theoretical attitude, which invited to thematise activities that – up to then – were unconscious and deemed trivial. It also resulted from the post-modern mentality that valorised individual strangeness and historicity, to the point of rehabilitating narration.

25A. Secret cabinet and transitionality: Witkin

The secret cabinet is enlightened with the notion of transitional objects according to Winnicot. What matters in the latter is not that they are such or such, but that, whilst being such, they open up and link to others, many others that share their statute more or less. What is valid in this case is not so much the object from which a human being (already an animal too) effectively and cognitively organises his environment that the more or less large transitionality, one that is more or less successful, activated on its occasion. If they are transitional in that sense, we can also say that secret cabinets consist less of images than of fantasies, understanding that the latter (for there are hundreds of definition) are images that are so available that they are no longer isolated and determinable, but that they activate the link of an individual with its environment. Topological, cybernetic, logico-semiotic link, it goes without saying.

Whether we speak of transitionality or fantasmatisation, photography suddenly seems very talented. It is appropriate to the multiple photo frame and the bric-a-brac, where photos can overlap each other without disturbing the one next to it too much, seeing as their perceptive-motor and logico-semiotic field effects are less coherent than that of paintings that destruct each other in the multiple photo frame. Specifically the traffics of development, printing, scratching, bite, crumpling, wear and tear of the negative or ulterior stages favour accentuations or erasing that allow ‘transitional objects’ to subordinate to their ‘transitionality’.

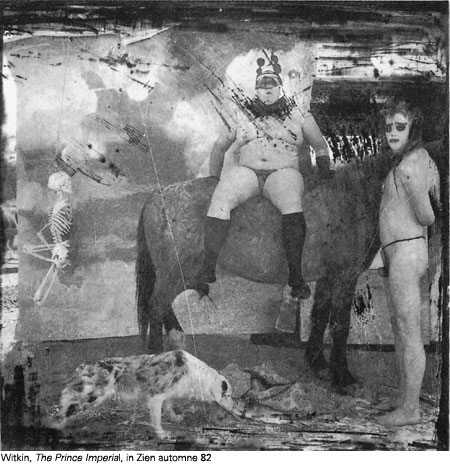

These aptitudes of photography to the secret cabinet became Witkin’s photographic subject. His themes were simultaneously imposed: ‘objects’ of sex, murder, decomposition, death, all function as stimuli-signals with animals, and as stimuli-signs in men. However, the matter was conferring them – through the photographic processes we have just enumerated – enough gaping inside themselves and sufficient transitionality between them for their sight to enjoy the availability of the fantasy (in the absolute sense) and that it does not coagulate in images, as is often the case in the ‘Stage Photography’ in the manner of Les Krims (PHPH, 98). The title of the book The frontiers of meaning suggests very well – through the floating sense of ‘meaning’ and the plural of ‘frontiers’ – that it is question of relations of objects more than objects as such.

Despite the founding myth that Witkins saw a little girl being run over and her head rolling on the pavement, he is probably at least as theoretical as compulsive. This is something we shall illustrate using Le Prince Imperial (*Zien, autumn 82, issue dedicated to stage photography) signifying how much this type of intention was in harmony with the post-modernist taste for the reactivation of faraway mythologies, a hundred miles from modernism.

|

25B. Monument and presence: Boltanski

The monument is not the multiple photo frame, coming across a thousand things. To the contrary, it strongly exudes something. Yet, it rejoins the multiple photo frame insofar as this thing is blurred. Like the flame of the Unknown Soldier. Like an arch of triumph, whose triumph we soon forget about, despite its high and low reliefs. Like a tomb and its unthinkable content. To end, the monument is a presence more than anything, soon a pure presence ensuring even more the cohesion of the community than the ‘rests’ of which it testifies are more evanescent.

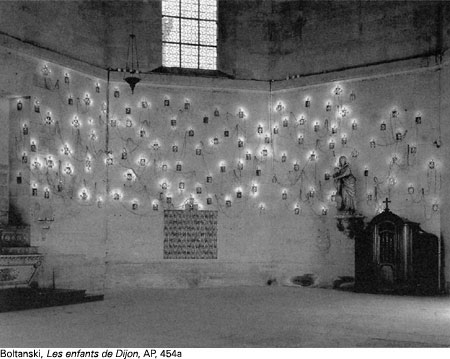

Boltanski, whose practice overlaps much from photography and who does not like to be defined as a photographer, turns around the monument. He made clothes displays, which being indicia, are very presentials. ‘We have all experienced this with the death of a family member. We see his shoes and we see the form of his feet like the hollow image of the person in negative’. Hence-understood (re)surections are true or false – or more precisely, fictional – and we shall never dissociate their author the artist and the clown or the hassidean. These practices were attributed to Boltanski’s childhood. He was abandoned by his mother and raised by his father, and many imagined a childhood that, in reality, he did not have. We must go beyond psychology towards metaphysic – that of the double tradition of Christianity and Judaism, of the vincible disorder and invincible chaos, of the resurrection of a glorious body and the resurrection of a physical body, of rationality and Hassidism – that photography and its indices conveyed in many ways (as shown in 1985’s Les Enfants de Dijon (**AP, 454a)), this ensemble of photographs of children monumentally regrouped in front of the apse of a Burgundy church.

|

There, everything converges towards presence, almost pure presence. The photographs of the children, re-photographed or not, were framed, because, for the vivaciousness of the presence, the frame is often more important than what it frames. In any event, they are humble: the presence does not have the crazy pretences of the conscious. The ensemble does not so much evoke than it represents, meaning calling with the soft, low voice. Finally, the presence looks over in the lamps haloing the images. It is so much the evoking light that matters, more than the features of the faces, than the electric wires bringing the current go in front of the photos, erasing them as information, intensifying them as energies, as currents. Hence, in this ‘painted paradise where the harps and lutes are’, are the children alive or dead? It seems that this work was created on all saint’s day. Yes, they are a bit alive and a bit dead. A bit in reality and a little – or a lot – in fiction.

Death-life, life-death, it is the idea that we have of images, whatever they might be. Beneath the portraits, here is a curious altarpiece of 10 x 8 photos, not of faces but of crumpled papers, chaotic circumvolutions, abstractions between faces and brains, as sombre in their red and black contrast as the other photos are a warm yellow under their artificial lights. But do you not think that these crumpling also make images? Are as present as images? To best answer, we shall go to the edge of the liturgy according to which our photographic commemorative plates adjoin an altar to the right, a confessional to the right, ‘true’ epigraphic commemorative plates, the Virgin Mary standing between heaven and earth.

Hence, this Christian wall is a Jewish Yabbok at the same time. It is the brother of the Monument, la Fête de Pourim dated 1988 (FS, 341). One easily goes from one bank to the opposite in both ways on the Jewish Yabbok, which is not the case of the Greek Acheron. In the photographic multiple photo frame, which is an indicial presence-absence more than information, and that whether it is a private or a public monument, we easily go from one bank to the opposite.

Photography as a Yabbok. Or still, like the illustration of the functioning/presence fundamental categorisation, which today is perhaps replacing the world/conscience categorisation, that dominated the Western world.

Henri Van Lier

A photographic history of photography

in Les Cahiers de la Photographie, 1992

List of abbreviations of common references:

AP: The Art of Photography, Yale University Press.

FS: On the Art of Fixing a Shadow, Art Institute of Chicago.

PHPH: Philosophy of Photography.

The acronyms (*), (**), (***) refer to the first, second, and third illustration of the chapters, respectively. Thus, the reference (*** AP, 417) must be interpreted as: “This refers to the third illustration of the chapter, and you will find a better reproduction, or a different one, with the necessary technical specifications, in The Art of Photography listed under number 417”.