DENIS ROCHE (France, 1937),

MAPPLETHORPE (U.S., 1946-1989)

The avatars of narcissism

The self-portrait seems as inbred to photography as figures. Is there anything simpler than turning the camera towards a mirror where one is looking at oneself and provoking the click? Southworth – the Nadar of the American daguerreotype – must have thought it for a moment when he took a photograph of his naked chest à la Byron in 1848 (AP, 31). Yet, the problem is not that simple. As in the case of figurality, we had to wait for the radical questioning of the 1970’s before photographers could envisage the photographic narcissism in all its implications. Even if this meant realising that WORLD 3 is more apt at interrogating Narcissus and testifying of its reversals than rejoining him.

Not everyone can be Narcissus. The genuine one, the Greek, as he leaned into the water and drowned, closed the buckle between him and his ‘form’, meaning his ‘whole’ that consisted of ‘integral parts’ according to the fundamental theme of WORLD 2. Or still – as he could only see his contour – to grasp his completed figure, scheme of the microcosm.

The Christian autobiography was something completely different. It supposed a redemption in relation to which the individual totalises himself as a Me in becoming faced with a Last Judgement, transcendent with Augustine, immanent with Montaigne, transcendental (proto-Kantian) with Rousseau. When Proust dedicates thousands of pages to himself, where is more: in the described or in the describing? The same goes for painters. When Rembrandt, taking advantage of the improved mirrors of his time, seeks his destiny through sixty or so self-portraits spread out over thirty years, he stumbles across too-perceivable bloats of skin and too elusive glances. The only ‘Rembrandt’ was probably he that was his pictorial subject. Just like the best-achieved ‘Proust’ was a language subject, not a theme.

Photography is even more disappointing for Narcissus. As soon as 1901, Steichen’s Self portrait with paintbrush and palette (BN, 172, FS, N° 173) showed us that, reaping as much Real than Reality in its non-scene, the photograph disperses the individual photographing photographed to leave him with only his photographic subject, which, being less controllable than a pictorial subject or a language subject, is also a lot less determined. Cindy Sherman’s head in the mirror, dated 1980, is entitled Untitled (*FS, N° 327).

|

Let us say it positively. If photographic subject related to narcissism, it is always by derailing it, or by turning it more or less. We shall discuss three of these reversals in the era covering 1965 to 1980, and will note that it is the epoch of happenings and performances, which were simultaneously the ultimate peaks and reversals for Narcissus.

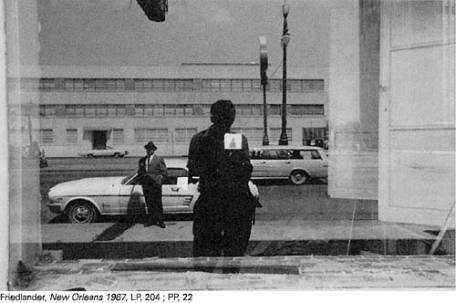

23A. The additional environment: Friedlander

Apparently, there is nothing less narcissist than Friedlander’s photographic subject, which is the reduction to the thin plane of the photo of the planes of the show spreading out in depth, through the convex sparkle of all the hence planes folded over. This party demands high definition, defies the subtlety of the prints, and prefers the frankness of the print to the point that, very often, the photographer was forced to be his own printer and editor.

Since we are dealing with omnipresent convexity, the histories of photography that can only show three or four photographs remembered Friedlander in plethora of phallic statues, large lit screens, huge skips lifted among violently erected building, many poles, pylons and water valves (AP, 332-337 ; FS, N° 362-364). This is exemplary, but let us not loose sight of the fact that his vision also extended to a few flowers, a bunch of branches or a humble barrier. For an embracing view, we shall rather refer to the ‘Photo Poche’, where the selection and comments of Loïc Malle display the most perfect comprehension of this photographic subject, subtle enough to have held the interest of Walker Evans, who prefaced an exhibition.

Let us come to the narcissism testified by the book published in 1970, bearing the title Self-Portrait. Firstly, let us note that this is almost the result of chance. The sparkling folding-over of several convex planes on a fore plane – Friedlander’s photographic subject – incited to multiply mirrors and windows. Hence, the photographer often appeared reflected. So much so that, revisiting the negatives of several periods like those that he used to do (someone that folds over the far away folds of space may also enjoy folding over the folds of time), he noted that he had there – if he pruned a little bit – some material that would later become the Self-Portrait. This takes us far from an ordinary narcissist scope.

The difference lies even deeper when we note the modest place that our Narcissus occupies in the photos of Self-Portraits, for instance in New Orleans 1968 (**LP, 204; PP, 22). It is true that the photographer figures there in the vivacious white square. For the rest, the photograph ‘is’ these two widely-opened doors, or rather, a powerfully-opened door and its reflection, where the skyscrapers mirror; two illuminable poles; a strong beam coming forth from above and that answers to a shadow-beam projected bellow. In the background, the horizontal, heavy rectangles of a Gropiusian building and long, inflated cars; finally, standing men, the man before the car as a third beam, standing this time. In a word, we go back to the lesson of Robert Frank i.e. that, in the United States, the substance of individuals is their environment. In our case, the substance of Narcissus-Friedlander is New Orleans, where he intervenes as a reflection among others. Elsewhere, it is other cities. So much so that each reflection of these various places is only ever one self-portrait, likes the singular form of the title suggests it. The indecisive figure in our little square signals the ‘retirement’ of the photographer as much as his entrance on the scene.

|

Twisted minds will want to add something. If Narcissus is the desire of finding – before oneself – a strong resonance that comes back to one, even completing the one (we no longer say : the me), is it so surprising that a photographic subject that has moved forth the content as a form among forms be the same as the one that produced the Self-Portrait ? After all, it is not so bad to buckle up ‘on’ and ‘by’ New Orleans. Rather than being evacuated by WORLD 3, Narcissus-Friedlander only converted himself to it.

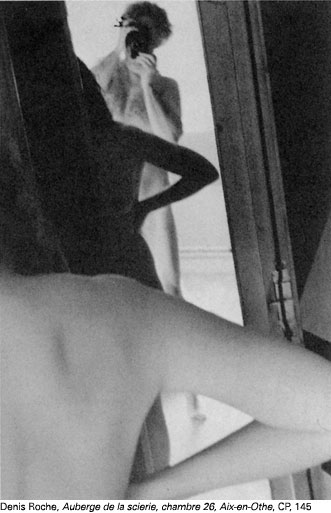

23B. Reciprocal and proprioceptive tact: Denis Roche

And if now the Narcissus of WORLD 3, unable to look at himself, attempted to touch himself? Supposing that he was a photographer, inventing – on this occasion - the tactile – and even proprioceptive – photography, a photography where perception is not only a perceived data but a perception action, a presence of the perceiver to his act of perceiving, an experience à la Merleau-Ponty culminating when the perceived is himself perceiving, hence in a reciprocal tact, where each perceiving and perceived is a perceiving-perceived, and perceives the other as a perceived-perceiving? This must not be easy, judging by the efforts deployed by Brassaï, Robert Frank, William Klein, or just now with Friedlander, to obtain a simple intro-reverberation of the place, despite the Cyclops eye of the Camera Obscura.

To clasp the buckle of touched tact, Proust’s literature had partially succeeded through its capacity of reminiscence, where the echoes of time lead the echoes of space. When Chateaubriand shouted ‘Leonidas!’ on the ruins of Sparta, the echoed name responded, simultaneously the voice of the other and his own voice. Hence, to obtain the expected effect, Denis Roche first doubled his work of photographer with texts, creating language echoes around photographs that themselves were already echoing others through spatial similitude and temporal differences. However, this solution remains extrinsic to the medium. Let us see its intrinsic solution.

To build a photographic device that has the properties of a tactile relation, one must first dig a depth that is not immediately distributable, like through the eye, but that forces to a progression and regression that is hesitating, tentative, viscous, like the exploration of the touch. Let us recall that the latter has separate endings to feel large or narrow, superficial or deep, hot or cold, delimited or pressed. The evolution in depth must also be plastically ambivalent, each plan being referred to the others in such a way that it is both before and behind. This is probably the essence, and is illustrated enough in the Auberge de la scierie, chambre 26, Aix-en-Othe, dated 1987 (***CP, 145).

|

More or less indispensable additives come and add to this essential. The first is the projected shadow, the tact and the comeback of tact, the nearest tact comeback, under the condition that it is in turn non frank but hidden, too short or particularly too long, interrupted or interrupting, taking shape (CP, 4, 152). The intervention of a mirror may also help to the tactile return – under the condition, like the shadow – that one does not really look at what would exteriorise and make figural, but that one intervenes diagonally (CP, 145), in bias retro-vision (CP, 134) or undone by the structure of what reflects in it. The obscene artificial flowers in a Merida frame hesitate between fake mirror and fake painting (CP, 128). Finally, in order that perspective should become reciprocity and not spread out without reprise, the top part of the show will often be decapitated (CP, 137, 139). Its bottom part will appear either too close or too far so that the volume implodes, particularly if the entire show is subject to a global roll and pitching, as in Robert Frank’s work.

In summary, this photographic subject sums up in the elementary catastrophe of the pleat with a fold, with its median fissure and its double inflation of volume, shade, and light. Let us add, in this potential opening and closing, a forcing aspect (‘forcing’). The cover of the special issue of the Cahiers de la photographie is almost completely filled by the double fold and the pleat of a newspaper waving in the air in 1984 (CP, 135), whilst the 1985 photograph opening the portfolio (CP, 121) has an ostensible double fold, dated Zwiefalten, etymologically ‘two-folds’, ‘double-fold’.

The themes are thus predictable. It is assuredly the own body – because proprioception could only be built from an own body – that is often present as a hesitant projected shadow, or from the back as it fits the referential that it is here. This initial body summons its sexual complement that not only ends the proprioception in the Shakespearian ‘double-backed beast’ but is also – as the naked female body the place of the double fold and the pleat per se. Still, for the echo to be spatial and temporal, it is preferable that this woman should be his woman. And even that the buckle of resonance, thus closed for the past, doubles for the future in the descent, not in the form of a present child that would tear the fold, but of the prenatal child swelling the belly and the nipples (CP. 137).

|

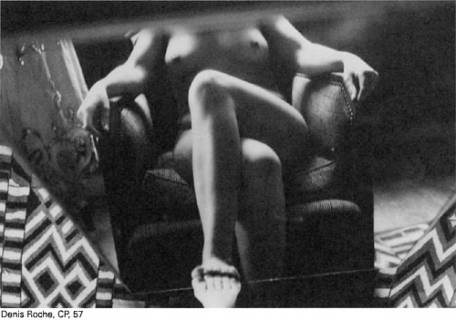

As to the shared place of the circular proprioception, it is the room, with its curtains, its mirrors, its smells and confining lights, particularly the numbered hotel room, allowing both the recurrence and the reflexive interval. In this place – which is still wide – the immediate place shrinks, the square and heavy armchair, causing the bodies to be internal resonances from the start, and virtually ‘forced’. The covers resume the folds of the nude (CP, 135, 122). On the carpet, the Zapotec motive, constrictive like all that is Mexican, is a good summary of this photographic subject where constriction takes a wide part (****CP, 57).

In Denis Roche, we can see a writer who, brushing up photography at the beginning ended up opening and bringing back a terra incognito: proprioceptive photography. Or an Occidental with a narcissist and neurotic (‘forcing’) programme belonging to WORLD 2 (practicing the fundamental break: world/conscience that reigned until Sartre) and that, through the virtue of its medium, found itself in the midst of WORLD 3, activating the fundamental break: functioning/presence-absence, which could very well be ours.

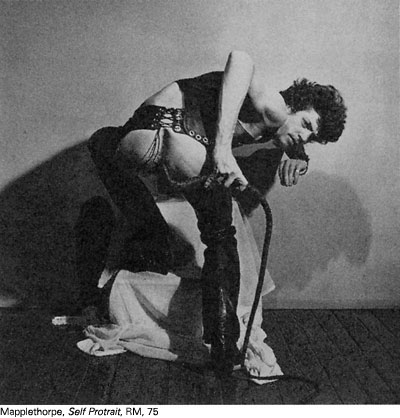

23C. The generalised penis: Mapplethorpe

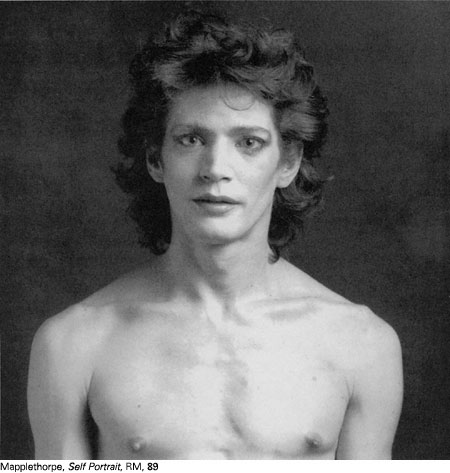

Before dying of AIDS in 1989, Mapplethorpe manage to elevate his own grave in the book-catalogue published on the occasion of the great retrospective of his work at the Whitney Museum in 1988 (RM). This was quite a lot for Narcissus. Particularly as we find eight self-portraits (RM. 17, 30, 35, 73, 75, 89, 109, 165).

Further to these direct manifestations, the narcissist impulse is indirectly omnipresent. Mapplethorpe – different from Duane Michals in that sense – belonged to a category of homosexuals that can declare, like Jean Genêt: ‘The tail was confounded with Harcamone; never smiling he was himself the severe penis of a male of unnatural strength and beauty’. Hence, there is the identification of Narcissus to an organ. The Whitney’s Robert Mapplethorpe shows at least three penises, the first laid down on the altar of sacrifice and ostentation (RM, 49), the second produced by the very strict clothing of a headless person (RM, 95), the third responding to the five, spread-out fingers of the hand (RM, 105). For Mapplethorpe, the fantasy of this organ extended to every flower, shaved head, bust of men and women, skin fragment, it is because everywhere in the 110 illustrations of the book-catalogue, we find the same motive, and hence Narcissus in his essence.

We are simultaneously at the heart of Mapplethorpe’s plastic subject, which convokes a sculptural subject of the sculptor and the photographic subject of the photographer. Obviously, the penile obsession aims at a structure of erection, shooting up and resurrection (as shown by theologies) – that only sculpture is capable of achieving – sometimes in the strictly sculptural assembling of Mapplethorpe as in St Andrew’s cross White X with silver cross (RM, 124) and the shield of David in Star with frosted glass (RM, 125), at times in devices where photography only intervenes as a derived element, such as 1987’s glorification of Andy Warhol (RM, 173), where a circular photo is inserted into a black square itself placed in a Byzantine cross and that should not be read : photo>mandala>cross ; but indeed : cross>mandala>photo.

However, the penile obsession does not aim a surging up structure. It is also a stretching texture. The penis, turgescent organ, erection and remission, organ that is not made but that must be made, is phenomenologically a skin. Mapplethorpe’s tender and furious desire wants that skin to be thin, elastic, semi-transparent, grainy and venous. Only photography, with its granulating films and its infinitely precise and allusive lighting, could provide it. A sophisticated studio process continues in each petal (RM, 194), in each leaf (RM, 199), in 1988’s Breasts (RM, 193), in the cloth over the altar of Cariton (RM, 202). Even the woman, although she is crossed out (RM, 187) or evanescent (RM, 197), refers to what Joyce called the ‘languid and floating flower’. We shall be attentive to two decisive choices. The Whitney book-catalogue ends on 1988 Nipple, an extent of skin, with only pores and the barely emerging allusion of the central stud. The cover only represents the mouth and the nose of 1988’s Apollo, conjoining the structure and the texture, the turgescence and their elasticity in their pure whiteness.

|

We now come to the explicitly sadomasochist works. When Narcissus appears whole – as in the 1978 Self Portrait (*****RM, 75) – his anus and his head, through their transversal disposition and their directional reversal signal, despite the spine that links them, the zonal and impulsive heterogeneities of what we naively call an organism whose derailing ends when the spine continues in a whip. For a certain unity to occur despite everything, the ill-assorted then call upon the theatre that, in catholic milieus, will be the service (the mass), itself reiterating the Passion and the Calvary. The stepladder figures the walk up; the highest step is the altar. On the cloth of the altar, the sacrament of the sexual organ is placed beneath the consecratory penetration of the whip in the ‘bronze-eye’; the sacerdotal ornaments are those of ‘leather and bondage’ SM groups; and perhaps a pleat draws a knife (the sacrifice of Abraham?). The phrase by Sade: ‘the altar is prepared, the victim climbs it, and the sacrificer follows her’ is accomplished in the coincidence of the victim and the sacrificer. The real death by AIDS ratified the fact that – in this type of homosexuality – the theatre is not a game, it is redemption.

All these forms, which are partially figures, must not distract us into forgetting that the last word here is given to transparency. Transparency saves in the end, in the glorious Jesus dated 1971 (RM, 20) or still, in 1987’s Andy Warhol (RM, 173), inspired by Edward Rushca’s Pure Ecstasy dated 1974 that the Whitney catalogue carefully reproduced at the beginning of the book (RM, 15). Even the detailed dramatization of our sadomasochist Self Portrait of 1978 (*****RM, 75) ends up glorifying the floral subtlety of its blacks and whites.

This is how the 1980 Self Portrait (******RM, 89) is hallucinated. It seems that this time, Narcissus does not need to ask for anything. He is shot from the front. He is not inverted left right like in the water of the fountain, but without inversion, like photography makes it possible. Decidedly, transparency plays its tricks. There, in Greece, he drowned. Here, he is transfigured in the diaphaneity of opaline.

|

Henri Van Lier

A photographic history of photography

in Les Cahiers de la Photographie, 1992

List of abbreviations of common references:

AP: The Art of Photography, Yale University Press.

FS: On the Art of Fixing a Shadow, Art Institute of Chicago.

BN: Beaumont Newhall, Photography: Essays and Images, Museum of Modem Art.

LP: Szarkowski, Looking at Photographs, Museum of Modem Art.

CP: Special issue of “Cahiers de Photographie” dedicated to the relevant photographer.

The acronyms (*), (**), (***) refer to the first, second, and third illustration of the chapters, respectively. Thus, the reference (*** AP, 417) must be interpreted as: “This refers to the third illustration of the chapter, and you will find a better reproduction, or a different one, with the necessary technical specifications, in The Art of Photography listed under number 417”.