RALPH GIBSON (U.S., 1939)

Immanent figurality

After the program of radicalisation and conceptualization of 1950-1975, it was only natural that photographers should thematize one of the basic characteristics of photography, its propensity to extricate figures. This propensity is so strong that we saw it as soon as 1865 with Margaret Cameron. At this occasion, we had briefly defined the notion. We must insist.

The figure is not the form. According to a strict vocabulary, the form belongs to the living and to technical objects. A resting or hunting lion has a natural form. A table constructed or under construction has a technical form. A forest is partially a natural form and a technical form.

A figure is therefore the representation of a form by contours and major articulations. We say a geometric ‘figure’. Insofar as the figure extricates, essentalizes, abstracts the structure of a form (formae figura, says the Latin). Hence understood, the figure is not straight, at a distance, taken out of time, congealed, taken out of any precise causality. Yet, in the same time, it is also virtual, bloated with possibles, prophetic (Pascal’s ‘figures’ of Christ), filled with omen and numen (nodding of the head/shaking of the head, by which Zeus took his unpredictable decisions in relation with the concrete forms of daily life). A door or a corridor – with something that moves back or forth slowly – is a figure in this last sense. A central mass between two smaller masses (the man between the two beasts of Baltrusaitis) is also a figure, and not only a referential sign of the triad, domination, mediation, etc. A form viewed in a mirror looses its volume, and particularly its mass, it leans in turn towards the figure. Sexual positions in the Indian temple of Khajuraho are figures more than forms.

Photography, and this is a singularity, has an acquaintance with figures. A literary text can speak of figures; it is rare that it is one itself, except through dispositions that are usually beyond the listener and the reader. Bach’s music is also filled with multiple figures, but again they are only accessible to the initiated. Traditional painting, proceeding from stroke to stroke under the drive of a hand and a brain, would almost fatally engender not figures but forms. And if Magritte is often figural, is it not because, also being an advertiser, he thought photographically? Indeed, photography works through the contrast of shadows and light. Since these are produced all at once, the framing often groups single panes that have the abstraction, detachment, and therefore the ‘ominous’ and ‘numunous’ strength of figures. On the other hand, photography, without being a mirror, has some of its qualities of thinness and timelessness, where massive and substantial forms quickly change into virtually figural working drawings.

In 1865, with Margaret Cameron, figures still largely belonged to WORLD 2, hence swirling into allegory: the two kissing children in The Double Star represent a double star, as the title warns us. On the other hand, the characters we met with Ueda and Suda, outlined and sampled by their non-mediatizing arabesque, if there was anything figural about them, it was by presupposing, as always in Japan, a grasping-construction through functioning elements, meaning WORLD 3.

We resolutely enter WORLD 3 with the figurality of Duane Michals and Ralph Gibson, who each take though completely opposite directions.

22A. From form to figure: Duane Michals

Generally, photographers do not make theories. And even when they do, they do not explain their reasoning point by point. This is not Duane Michal’s case, as he practices a narration in images, whose photos are usually accompanied by accompanying texts that are ‘figural’ like the images, and archetypical like those in photo romances. In a word, we only need to follow him. And this is what we are going to do, leafing through the suite of stories he assembled in ‘Photo Poche’, whose selection and order are of the greatest importance. There is no pagination, which will force us to mention the title every time, not a bad thing.

He starts with a six-page declaration of homosexuality: Fortuitous Meeting. Then, he gives the most evident plastic consequence of the homosexual situation as he lives it, the transformation of meaningful forms into figures, and particularly into glorious figures. This is what happens to his Andy Warhol in three images, whose face first offers a form that is already double, lived in by another form, to the point that it blurs into the second image and fades away in the third until it achieves a glorious illumination, as we say a Christ in glory, a pure figure.

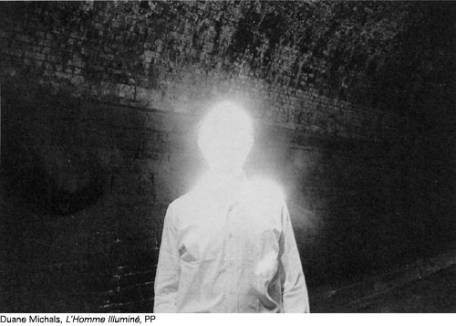

One finds a being-itself-and-other in homosexuality, something that Proust described at length, where every perception and every imagination are also itself-and-others in multiple or indefinite superimpositions that are not devoid of ecstasy. Yet, the figurality provoking ecstasy can be contained in a subtle luminescence – as we usually encounter with Proust – or violent, such as the light that struck Roland Barthes in some of Racine’s characters. Duane Michals encounters this vivacious glory, this striking by lightning, and not solely in his photograph of Andy Warhol, the saint. The Human Condition shows us how, on the platform of a train station, a beautiful young man can – in six images – transform himself into a nebulous spiral. Illuminated Man (*PP) resumes the striking glorification in one sole detached photograph that, for this Christian – specifically catholic – homosexuality, is consonant with the transfigured Christ, ultimate object of identification, in Christ in New York.

|

However, we will note that, for this striking, glory is partly related to the screen. Another Andy Warhol concluding the volume shows us his face, hidden behind his long hands, another figure. Similarly, we must note that, insofar at it strikes, glory is both life and death, as La mort vient à la vielle dame shows us to the point of provoking the question: ‘how can I be dead?’ in Le voyage de l’esprit après la mort. Finally, in this Christian context, the entire game of being-itself-and-other is not guiltless, and the figure of mire becomes, after the intercourse, the figure of the repenting man in L’Ange Déchu. In any event, we should never dichotomise: glory or eclipsing; light or disappearance; triumph or sin. But replacing the or by the and. The homosexual practice of the inclusive disjunction privileges the Acrobats, in a group and by twos in particular (PP). Besides, it is the and-and that pushes Duane Michals to the narration in multiple images – as Jean Genêt was pushed to the theatre – or more exactly into ceremony. Unless one single photograph – for instance that of the lesbians in Certain words must be said, where one is the figure of the towards-the-inside and the other is the figure of the towards-the-outside – is intrinsically double. Like glorifications.

We easily see how this passage from form to figure could or should call upon photography. Through his successive exhibitions, the latter facilitates superimpositions. Glory is achieved at best through solarisation. Particularly the way in which the shooting can – at leisure – bring the object closer or further or turn it top/bottom, back/front, committing it to every metamorphose. In Take One (a pill) and See Mt. Fujiyama, the woman standing out as a global form in a window frame in a first while, figuralizes in low angle shot, inflates at great angle, turns around – still as figuraly – then becomes a figure of oppression and night, then a glimmer on which the figure of the Mount Fuji stands, as it prosaically comes back to finish off the form of the masculine underwear erected: form > figure(s) > form. In a word, figural photography can promise Paradise Regained to some form of homosexuality, which is something that the cinema would be quite incapable of doing, as it does not proceed to a succession of immobilities, but by a sequence of movements.

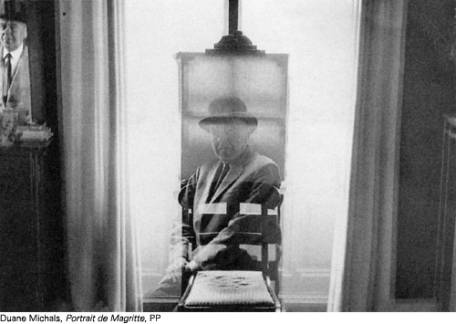

Usually, in Duane Michals’ work, superimpositions, over-expositions and variations of angle are at the service of his own figures. Yet, in the portraits, they are also capable of functioning at the service of other figures, like that of the very figural yet very heterosexual Magritte. In the work of the latter, the figurality is not the result of evanescence but of the frontal over-density of forms, like that of the bowler hat, incapable of communicating because of their density itself. In 1965’s Portrait of René Magritte (**PP, or Life, Themes. 115), we shall leave the reader deduct from the Magritian figures: frank reflections before a mirror; transparencies, but within the strict frame of an easel; scenarity, but defined by curtains whose pleats are tensed in ionic striations; multiple poses, but that are systematically decided, etc. And we shall suspect how many adaptations must have taken place between the portraitist and the portrayed.

|

22B. From figure to form: Ralph Gibson

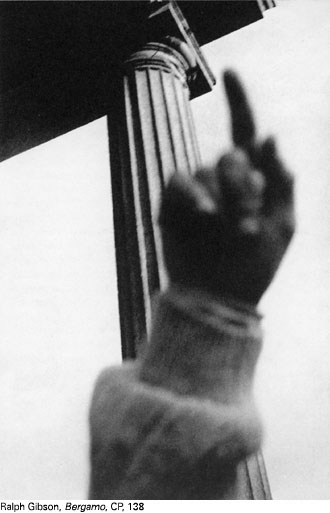

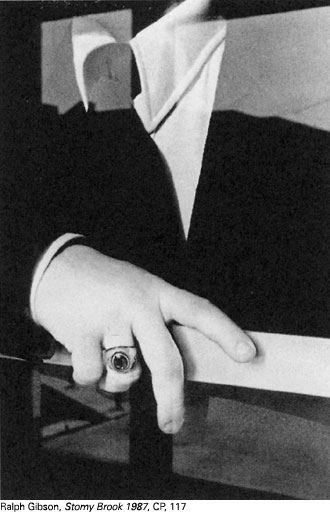

Ralph Gibson follows the opposite path to Duane Michals. With Gibson, we never go uphill from the form to the figure, the form ensues from the figure, which itself ensues of the photographic frame as a physical departure data. To illustrate this deduction, we reproduced Bergamo 1987 (***CP, 138) and Stomy Brook 1987 (****CP, 117). The enumeration that follows is not only pedagogical, but it belongs to the essence of the reasoning.

|

(A) The photographic frame as such is the figure of figures, the original ‘numen’ and ‘omen’, with its physico-chemical limitation that decides yes/no, like Zeus, a portion of space from an absolute cut-out, sacraly separating it from any other space and any other time (se-cernere is a possible etymology of ‘sacred’). (B) With each click of the camera, light and shadow – since we are in the field of photography – come and settle here, before any determination, before even being day or night. (C) Through the encounter of the composure frame and the light/shade couple, vertical lines tend to affirm themselves on horizontals, seeing the system – optically and kinaesthetically – privileged by the standing primate with its gravitation and counter-gravitation indexed from bottom to top and its cerebral and physical asymmetry from the right and the left. (D) Among the resultants of these forces, the distinct and the confuse can emerge figuraly with the hard and the soft like all the great topological parties, meaning the RATES of close/far, open/closed, encompassing/encompassed, penetrating/penetrated, compact/diffuse, sharp/obtuse, or still pleats, gathers, etc. (E) In the meeting of general or differential topology with gravitation the lineaments of geometry of proportion articulates (Euclidean-Cartesian). The stud is the frame or the 35 mm format through its proximity of the golden number, invites to a distribution according to the gold section, harmonious relationship where great is to small like the sum of the two is to the great. (F) Finally, ‘things’ (causae, causes) begin to become defined, hence the bunch of operating relations in course of objectalisation and nomination. The hard-clear and soft-floating have become a hard-neat spine and a soft-floating hand, or elsewhere a soft hand on a hard support (CP, 117). But the later the better, since each has stayed, as long as possible, non-mediatised, irreferable, irrefutable, immense, without measure.

|

We must go back to Vision, which we quoted before with Giacomelli. After having proposed the computational steps that, from the retinal data lead to the perception of a three-dimensional object (object centred), David Marr asks himself how the hence-perceived object could still be named, hence situated in classes of objects. He proposes that this classification should be operated through a reference to an ideal cylinder whose amount of segments and the proportions between the segments characterise the object. According to this point of view, Italian Giacomelli and American Gibson complete each other. If we take as a starting point the moment of the object perceived at three-dimensions (object centred), Giacomelli would take us upstream at this stage – which are at most of 2.5 dimensions (viewer centred). Gibson, on the other hand, would have us come downstream according to the progressive specifications of the cylinder of nominative reference, but would stop us just before the completed nomination.

This is for the epistemological aspect. And, indeed, instead of being signs, Gibsonian objects, which remained figural, would hence keep their statute of stimuli-signs, human correspondents of the stimuli-signals in the animal world. This is the case of a shoe (CP, 118), a collar (CP, 117), an anus-flower-star-eye (CPJ07). Whereby – probably – this sort of (immediate) amazement caused by Gibson.

The main thing, when looking at these photographs, is not going down too quickly, we should go down as slowly as possible the suite of steps that go from the frame with its ‘ominous’ and ‘numinous’ virtualities, to the denomination of particular objects. Hence, it would be an unfortunate precipitation to immediately see and name in the photo New York 1974 (CP, 136) two women faces, one three-quarters and the other being a profile, one in the light, the other in the shade. In the special issue of the Cahiers de la Photographie that we are referring to, this photo was judiciously published across from the Bergamo 1984 (CP, 137), whose similitude is blatant although different classes are modularised : ‘bottle’, ‘window’, etc.

Through this similitude in difference, we could not grasp better the general suite that is shared everywhere: frame > shadow/light > vertical/horizontal > hard/soft > etc. according to the deduction produced above. And it would be an equally abusive precipitation to reduce the Gibsonian device to a fetishist or homosexual fantasmatization under the pretext that the mouth or the sexual organs are almost always erased by the shadow (CP, 130) or by an excessive clarity (CP, 132), or still, displaced in the Freudian sense in a lunar sublimation (CP, 126).

We understand Gibson’s attachment to Italy. Because figurality as he practices it finds his ancestors in Pisanello, Mantegna, Signorelli, Angelico, Piero di Cosimo particularly in the goldsmith-headwear of the Simonetta, to which an implication is perhaps made explicitly (CP, 122). The parallel to which we were forced with Giacomelli confirms this acquaintance. As Swiss Robert Frank was taken aback by America more than any American was, American Gibson is taken aback more by Italy than any European native. A photographic subject is above all a question of amazement.

Note : MATHEMATICLA FIGURES AND PLASTIC FIGURES

Ralph Gibson declares the implication between figures and index (vs indicum), or indexations. To conclude, would figures not be these forms where the index-indexations, empty referential signs (without determined referent) would be prevalent? Do they not supply the tangible element of mathematics, which are the practice of the general coordination of index (or best, of indexations), i.e. pure signs of direction (Euclidean geometrization), of succession (ordinality) and collection-repetition (cardinality)?

In truth, the plastic figure overlaps the mathematic figure since, as Bergamo 1987 warns us (***CP, 138). It comprises the (top/bottom) gravitation and the (right/left) laterality in a ‘physical’ manner, which sends back to Physics. The ‘to the left’ and ‘to the right’ of the mathematician are only oppositives, structuralists in the narrow sense. Many experimental studies on the plastic phenomenon are ineffective because they do not take into account the ‘physical’ gravitation of the forms and figures perceived.

Henri Van Lier

A photographic history of photography

in Les Cahiers de la Photographie, 1992

List of abbreviations of common references:

PP: Photo Poche,Centre National de la Photographie, Paris.

CP: Special issue of “Cahiers de Photographie” dedicated to the relevant photographer.

The acronyms (*), (**), (***) refer to the first, second, and third illustration of the chapters, respectively. Thus, the reference (*** AP, 417) must be interpreted as: “This refers to the third illustration of the chapter, and you will find a better reproduction, or a different one, with the necessary technical specifications, in The Art of Photography listed under number 417”.