Luminous pleating

The thirties are not exclusively centred on the recession and the famine in certain US states, the end of the great seism of traditional representation of the three former decades and the streamlining of styling. It is also the sudden rise of Hitler and Mussolini, the wars of Spain and Ethiopia, preludes to the Second World War and its aftermath until the Korea and Vietnam wars. A new path was opening in photography. The latter now had an optic, chemistry and evermore performing cameras to follow rapid actions.

War photographers also had to find formulas to transform the instant in moment. But it could not be Cartier-Bresson’s ‘tukHè’. We witnessed the apparition of Hoffmann’s propaganda, McCullin’s picturesque, Eugene Smith’s explosive distinctness, and particularly Baltermants’ ‘figural’ epic at the measure of the Russian steppe combats in 1941-42. There was also a completely improbable solution, which consisted of placing oneself within or without good and evil, out of step of any current reference system. This was the inscription of the event in the universal pleating of a light that was both tender and generalizing; beyond life and death. Robert Capa’s photographic subject.

The posthumous Images of War, dated 1964, translated into Images de guerre by Hachette (IG), skimming over the twenty years covering 1936 to 1954 – from the year when Robert Capa ceases to be André Friedman to the year when he jumps on a North Vietnam landmine – is one of humanity’s greatest books. To an extent where we feel uneasy discussing it. We shall therefore content ourselves with juxtaposing certain astonishments and exclamations.

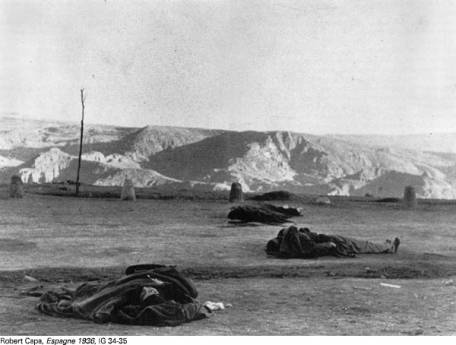

Spain 1936 (*IG, 34-35) – the dead are back in the landscape against which they stood for a moment. They have rejoined the eternity of their mountains, with which they now share the shapes and the tranquillity. The tree that has been exfoliated by the bomb indicates how we reached that point. Halfway between the virtual eternity of the geology and the transitivity of human bodies, military milestones erect their intermediary, secular longevity, that of the great signs systems. Hugging the pleats of the mountain, the clothes, the bodies, the light – which itself is pleated – appeases every detail, creating relays of the unanimous vastness. The frame does not index anything; it is a simple physical cessation of what goes over its edge. However, despite the richness of the contents, there are no internal multi-frames like we find in Adams’ work; the pleating unifies. An attentive and detached moment-state of universe.

|

Italy 1944 (PHPH, 91; IG, 80-81) – the Italian peasant leans and rests on the ground, his ground, resuming it. His upright stick hugs the folds of the ground so well that the hill itself designates the fleeing enemy, hunting it down. The two glances following the stick confirm that the frame is only the indicium of a fortuitous cessation, not an index that would break the luminous pleating of things including this, what we see, is merely a relay. The movements of the clothes support the general pleating.

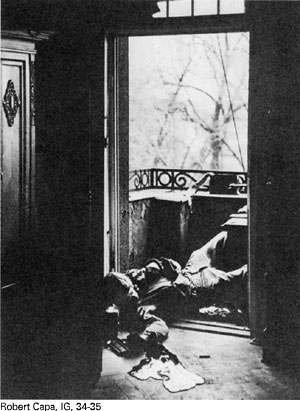

Germany 1945 (**IG, 149) – an American soldier has just been killed before the Armistice. The pleats of light fall from the trees to the clothes before reaching the puddle of blood. The metal balustrade works the non-scene, and on the wardrobe door, the lozenge of the wooden crest responds decoratively to the thick spot of blood that becomes a coat of arms. The photographer thought that this photograph would not be published, as it was handed in long after the war. This unnecessary photograph responds to the uselessness of war, he says. The conclusion of the text is cosmologic and devoid of bitterness: ‘Bah! The survivors will soon forget!’ It is undoubtedly to the honour of the great reportage magazines that blossomed just before the Second World War that these photographs – which are everything but anecdotic, escaping so much every warmongering or pacifist declaration of propaganda or sentimentality – managed to be published, thereby commercialized by the press for a wide audience. Here, we find no current psychology, no sociology of everyday life, not even a scientific or poetic anthropology. We only find the situation of mankind and the world in one extremity (that of war) supposing – to be grasped-constructed – that someone was sufficiently present and absent, there and elsewhere, now and never or forever, mixing tenderness and the implacable calculation to circulate with the same nerve through the solitary death of the battlefields, the offices of the Magnum agency – founded in 1947 – and the dazzling nights of Paris and other cities.

|

Of course ‘that’ – like any other photograph – ‘was’ never either. It is – accordingly to the words of Stieglitz, Ansel Adams (and Claudel) – a question of equivalences. John Steinbeck, the long-time companion, is unequivocal: ‘He created a world, Capa’s world’. Steinbeck is even more enlightening when he adds ‘He could photograph thoughts’. Not his thought. Not their thought (those who were shot). The thought. When Capa said: ‘Ten years from now, witnesses will be able to say: this is how it was’, he was selling his product, like he could do so well.

To obtain the luminous pleating by which the famous Spanish fighter, shot at close range in his fall is simultaneously a striking and an apotheosis (IG, 22-23), he had – in an echo to William J. Newton’s ‘little out of focus’ – to put himself slightly out of focus, title of his 1947 autobiography. He also had to capture war as a process, perhaps a fundamental process; according to the title of his last publication, Death in the Making dated 1937. In any case, Capa shares several traits with Atget: the division of light, the opened horizontality, the indicium-frame, the absence of any apparent rhetoric. Atget did not reinforce his prints, and Capa’s photos of The Landing at Normandy (PHPH, p. 43), which were mishandled when developed, encourage us to remember that the luck we call Reality is only ever a reflection of the Real, or in the Real. The destiny of Capa’s photographs in print confirmed their nature: whilst they were outrageously cropped, the Images of War preserve their miracle through the pleating of grey, whilst the others, which were not cropped but which flattened the blacks, are merely anecdotes.

To accomplish his legend, he who used to say that he always instinctively felt where he needed to stand to rub shoulders with death without dying or to obtain an order, ended up stepping on a landmine in North Vietnam. In 1937, Gerda Taro, his unforgettable photographer friend, stayed behind in Spain, crushed by a tank. Amateurs of psychological equations will attribute his invading warmth and his ‘slightly out of’ to the Jewish milieu he came from and his taste for imponderability (almost Kertészian) to his Hungarian origins. They will add that the combined warmth and imponderability is in fact tenderness and humour. And that the generalized luminous pleat is tenderness that became transcendental. For his funeral, his friends felt they had reached the right note in the Quaker rite.

photos © Robert Capa / Magnum.

Henri Van Lier

A photographic history of photography

in Les Cahiers de la Photographie, 1992

List of abbreviations of common references:

PHPH: Philosophy of Photography.

The acronyms (*), (**), (***) refer to the first, second, and third illustration of the chapters, respectively. Thus, the reference (*** AP, 417) must be interpreted as: “This refers to the third illustration of the chapter, and you will find a better reproduction, or a different one, with the necessary technical specifications, in The Art of Photography listed under number 417”.