BILL BRANDT (U.K, 1904-1983),

EUGENE SMITH (U.S.A., 1918-1978)

The colour of black

The negative shadow, the positive shadow, obscurity, and black are not all the same thing. The first is Hill and Adamson and Margaret Cameron from the start. The second, Steichen and Strand from 1900. The third, Brassaï, after 1930. We had to wait until 1930 for photography to discover black, for it to make blacks ring.

Technically, it would have been possible before. However, it is difficult to see what place the sounding blacks would have taken in the pictorial ‘soft focus’ or in Man Ray’s ‘astral effects’ or in Weston’s ‘straight photography’. On the other hand, among 1930’s photographers, which were turned towards the proximities and daily lives of this world, we understand that some may have attempted to grasp black as black, the dense colour of black. At the service of three photographic subjects that are not unrelated: Alvarez-Bravo’s constriction, Bill Brandt tellurism, and Eugene Smith’s explosion.

13A. Constrictive black: Alvarez Bravo

Constriction is essential in Mexican art, like in the entire pre-Columbian culture. This way of grasping every volume as though it was surrounded, clasped, compressed in every sense by another, by several others, like grains of corn. This constriction is most sensitive in the system of the Uxmal stones and in the compressions of Teotihuacan sculpture and called upon, in Bonampak’s paintings, reds and greens so dense that the result of their complementarity is a ‘black’ effect granted to the features, which are truly black, circling the figures. Here the environment intervenes for a great part. The Earth of Pedro Páramo, the « mera boca del infierno », essentially made-up of volcanic ashes, seems even blacker under the light of its sky, so brutal that it is also reminiscent of black.

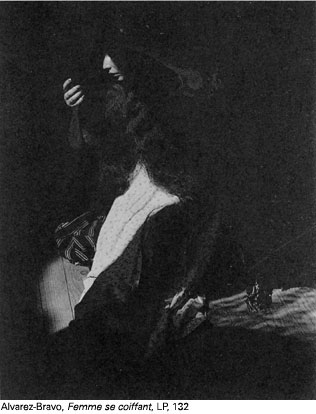

Alvarez-Bravo was raised in Mexico, in the neighbourhood of the cathedral. A few meters from there, we tread on the remains of the Aztec civilizations and a Spanish Christian church where we can verify the deep cultural collusion here previously existing between the invaded and the invaders. Like Mexico, Spain privileged the intrication of life and death in a direct black. Hence in 1937-38’s Femme se coiffant (*LPn 132), a human figure barely emerges, compressed among an invading black that is anterior to everything, a bat reminding us that in Monte Alban II there was a bat God, and probably because this mammal, just like man, only has a pair of teats and in principle one offspring per litter, but also because it represents the constriction of every deployment in the black encirclement as last truth.

|

And assuredly the encircled being is a young woman, in this country where, in the past, if one reads Sahagun, the ritual sacrifice of young girls was a significant lock of universal fluxes. Not a long way from her, in the same dates, Malcolm Lowry hatched Under the Volcano, whilst the colours and matters of painter Tamayo converted those of WORLD 1 of Bonampak in the functional elements of WORLD 3.

13B. Telluric black: Bill Brandt

The meeting between Germany, land of Empedoclean element, where he is born and educated, and England, mining country of which he will be a citizen and from which he receives his photographic « impregnation » – as Evans received his in Havana – situates Bill Brandt. When, in 1936, he titles his first book The English at home, we could be led into thinking that he is from the same mining province as English sculptor Henry Moore, his elder by six years, because he shares the same sense of telluric forces – in particular coal-related – with the twentieth century Michelangelo.

His Northumberland Miner at Evening Meal dated 1937 (**AP, 288) is not soiled by coal, he almost feeds off it, attentively assisted by his wife. We should compare it to Walker Evans’ Havana Dock Workers (MO, 52-57), which is dated almost the same year, to see to what extent what was a planifying valorizing modulating with them, testifies with him a resonance in rise and in depth. Never before – probably – had the relationship between the ground, the coal it exudes and the human being heating himself from it, almost feeding off it, has never been rendered with such ‘equivalence’ (in the sense of Stieglitz and Adams) than in the darkly grassy talus, the path, the heavy bag, the hand-pushed bicycle by the man who bends over it in the Coal Searcher Going Home to Jarrow, which is also dated 1937 (FS, 275). Bill Brandt’s mining black supports the most diversified things, from the raw energy of a pile of bridges dated from the 1930’s (ArtPress, p. 105) to the almost splattering cultural and moral sparkling of the Parlourmaids of the same era when it is clad in a white apron (AP, 289). A little after Brassaï’s Paris de Nuit, A Night in London had to follow.

|

A photographer of internal thrusts had to be attracted by great angulars. Brandt, who was Man Ray’s assistant in 1929, exerted this in 1953’s Perspectives of Nudes (PN, 255; FS 310), where again his bathers equalized in the mountains – again the kin of Henry Moore’s giants – are still the telluric turgescence.

13C. Le noir explosif : Eugene Smith

Eugene Smith, the American, used the colour black like a cloud of explosion, according to an acute angle where the movement does not move towards the point, as in Weston’s competition of fluxes, nor moves away from it, as in Dorothea Lange, but follows the eruptive breadth, usually from bottom to top.

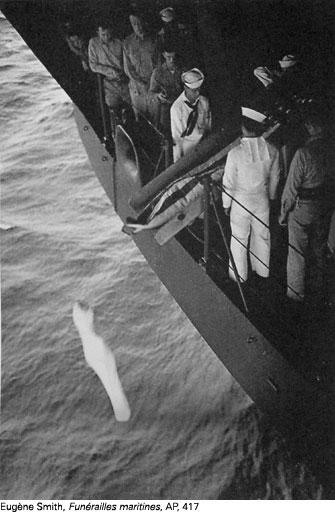

This system found an archetypal manifestation in Explosion in Iwa Jima, dated 1945 (AP, 415). Yet, it deployed in the most complex manner in the Maritime Funerals, dated 1943, during the Marshall Isle campaign (***AP, 417): the light triangle of the sea blown from the top left hand side corner, the dark triangle of the ship raised from the bottom right hand corner; finally, the contrast of the two triangles which is re-torn according to an acute angle that is re-opened by the three white rolls of the two standing sailors and the shroud draping the dead body falling into the water.

|

We shall note the permanence and the obviousness of the mechanism throughout the whole Eugene Smith production, like with Dorothea Lange and Kertész. Would it be that the photographers of the angularity, because an angle is obvious, are particularly constant? In any case, nothing escapes the patent system here: not the tip of the chin of the classic head of the doctor leaning over a wounded child (LP, 151), not the tip of the gun planted in the grass at Okinawa (AP, 416), not the hair of Albert Schweitzer’s bended head (BN, 288). Spain was going to offer Smith the opportunity of an exemplary reportage, because it is by definition the country of black and of the explosive angularness, and that the plough of the ploughman, the spindle of the spinner, the caps of the carabineers were consonant with his fantasy in advance on a background of Zurbarán (Life, Reportages, 72-81). As Bill Brandt’s telluric black summoned the great angular, Smith’s explosive angle summoned the telephoto lens, carrying the oblique of the face of a Pittsburg metallurgist in 1957.

Eugene Smith tried to create the ‘truthful’ photographic tale, where photos and texts would meet, such as the day of the famous country doctor called away from his fishing party to help a little girl victim of a horse’s head butt and losing an eye. An Accident Interrupts His Pleasure (PN. 226-227) was published in ‘Life’ in 1948, one year after Robert Capa and Cartier-Bresson founded the Magnum agency to ensure photographers-reporters some initiative in the selection of their theme, and a right to inspection on the publication of their photos. This was undoubtedly the era during which the reportage had the highest notion of its responsibility. However, it was obvious that, in Smith’s truth narration (in those days, Smith considered himself as the conscience of the trade), several images had required multiple and posed shootings, some of which with artificial lighting, and that the doctor’s departure for his fishing trip and his return had been replayed afterwards.

Henri Van Lier

A photographic history of photography

in Les Cahiers de la Photographie, 1992

List of abbreviations of common references:

PN: Photography until Now, Museum of Modem Art.

AP: The Art of Photography, Yale University Press.

BN: Beaumont Newhall, Photography: Essays and Images, Museum of Modem Art.

FS: On the Art of Fixing a Shadow, Art Institute of Chicago.

LP: Szarkowski, Looking at Photographs, Museum of Modem Art.

The acronyms (*), (**), (***) refer to the first, second, and third illustration of the chapters, respectively. Thus, the reference (*** AP, 417) must be interpreted as: “This refers to the third illustration of the chapter, and you will find a better reproduction, or a different one, with the necessary technical specifications, in The Art of Photography listed under number 417”.