The magnificence of plating

Dorothea Lange, evoked about Weston, already reminded us how, during the Great Recession, some photographers played a considerable role in signalling the misery and sometimes the famine that struck the South of the United States, in particular the cotton pickers. Walker Evans also worked for the Farm Security Administration. Like his colleague, he had an independent photographic subject from his possible social applications, which in his work were always intricate with his fundamental intention.

In a seminar organized by Beaumont Newhall in 1971, four years before he died, Student 9 asks him: ‘Is there a social comment?’ Evans is categorical: ‘Not in the least’. ‘But you can put one in there if you want to’. We should probably distrust the affirmations of an individual on his behaviour, but here, Evans does not affirm, he denies, and scrupulously insists ‘I don’t think there is a social comment’. Not satisfied with denying, he now almost impulsively indicates what should take the place of the negation: ‘I photograph what’s in front of me’, and ‘what attracts me. Half the time, I don’t know why. I was politicised by other people, not by myself’. The continuation of propositions is remarkable. He does not say: ‘what attracts me and what is before me’. He Says: ‘what’s in front of me and attracts me’.

Basically, in the thirties, and particularly since 1933, Walker Evans has – before the human being and his utensils – the same relationship than Ansel Adams before his landscapes. From both sides, it is the same magnifying and embracing astonishment. Except that, to create cosmological photographs among Yosemite, the serialization of light and the internal multi-frame were required, whereas to create among poor people and their utensils, the magnifying operation of the plating, which responds to a certain in front of was required. Plating here does not mean scrambling a motif to bring it back to two dimensions, but, to the contrary, grasping it in such a way that everything that is three-dimensional about it, all that could hesitate or fade away should deploy itself, taking its vertical and particularly lateral expansion, distributes itself placidly in a self-sufficient evidence, without even Dorothea Lange’s central bulge and angularity, nor Weston’s competitive fluxes, nor Brassaï’s inflations, and either laterally and frontally immense, without measure. The magnifying flatness in front of was Walker Evan’s photographic subject.

Let us remember that the plates of the cameras of the era, where the photographer considered his shot during the focusing, had at least three properties. A) they were big: 8x10 inches, or at least 4x5, hence sufficiently detailed to present (make present) an image that was explorable in every direction, particularly laterally, and not a simple pinpointing of what should be shot elsewhere and outside, as with an ordinary viewfinder. B) These plates were unpolished, which allowed for following with great precision the balance of light, indispensable to flatness. C) Everything was seen tipped over top/bottom, in such a way that the gaps between the objects were captured as well as the solids, that their coincidences or disagreements with the plan of the plate were blatantly obvious, that one perceived the weight of the plastic imponderability of each element (we proposed the top/bottom tipping over to oppose the imponderable Kertész and the ponderable Man Ray). ‘It’s quite an exciting thing to see’, exclaims Evans forty years later, in an answer to Student 17.

What were the themes that allowed, or triggered, the magnifying spreading out? Turning the pages of Havana 1933 (HA), perfectly published by Gilles Mora at Contrejour, we could think that Evans received what an ethnologist would call his photographic ‘impregnation’ in the Cuban capital after the Depression. As we see in Corner Dairy Shop (*HA, 45), in front of which Pietro della Francesca would have stopped to stare, the arcade constructions allowed the horizontal deployment and the marking out, barely articulated enough and old enough not to disturb the shot. The rest followed. On a butcher’s façade, the letters of CARNICERIA were larger than high, and showed constrictive pre-Columbian style recurrences, each being almost a Walker Evans (HA, p. 6, cl. 14). Everywhere, large white ‘surfaces’: the women’s skirts under the wind (*HA, 45), slightly faded military costumes (HA, 30). The boaters (straw hats) pullulate; these flat surfaces are eminently referable to the flat surface of the photographic plate (HA, 28). Even the wide feminine foreheads offer numerous parallel plans to the film (HA, 43, 44, 56, 59).

|

And if, in all that, a wall, a hat, a front, a skirt were not parallel to the plate, they nevertheless offered enough implicite planes in order that, when they sunk to the left, others sinking to the right insure – taking the lights into consideration – diverse congestions, physical and optical weights of details, produce as a resultant the flatness in the general outcome. To become initiated to this mechanic following a simple example, we can see how, at a barber’s shop (HA, 49), a vanishing to the back and to the front balance in the strictest of frontal (transversalized) planes.

Assuredly, the photographer had to be consonant whit the show, never accentuating a point (a ‘punctum’), a picturesque modelling, or still a semiotic modelling like a social message. When Evans crops, it is never to index a social message, but to comfort the plane. We have already encountered this imperturbable neutrality with Atget, although it served another topology. It was the cycle of erosion/recycling. Here, it is question of the utensility, the Heideggerian ‘Zuhandigkeit’ (quality-of being-for-the-hand), thought in the same era. Just like Sander’s motif was the role vis-à-vis the bodies, the ustensility of utensils vis-à-vis the bodies was Evans’ basic motif. The 1971 catalogue of his MOMA (MO) retrospective ends declaratively on the photograph of an armchair and a footrest, shot from the front in their maximal spreading. Already in 1937, the refugees of an Arkansas flooding were reduced to two bowls than hung from the tips of the hands that hung along the body (BN, 266). Beaumont Newhall, who mentions the example, must have seen that all of Evans’ work was there: two utensils supplying two human beings. Is there anything more fully flat than these dishes, – worthy of the boaters in Havana – one of which is strictly parallel to the frontal shot?

All in all, Evans was an archaeologist poet, just like Adams was a geologist poet. He does not worry about the poor and the utensils because they ask for pity, like (yet, are we sure?) in Dorothea Lange’s work, nor the social encouragement, as we sometimes find in Hine’s work. The famous 1936 reportage, whose text was written by Agee, bears the following psalm as a title: Let us now praise famous men. And the MOMA catalogue, which Evans supervised and inspired begins with an unambiguous text by Walt Whitman: ‘I do not doubt there is far more in trivialities, insects, vulgar persons, slaves, dwarfs, weeds, rejected refuse, than I have supposed...’. Which enlightens what precedes it: ‘I do not doubt but the majesty and beauty of de world are latent in any iota of the world...». We shall note the ‘beauty’, but particularly the ‘majesty’. And we shall remember that English ‘World’ is very different to the French ‘Monde’, which is derived from ‘woruld’, the environment as a horizon to every utensil graspable by man’s body and brain. Decidedly, throughout the work of Watkins, Stieglitz, Weston, Dorothea Lange, Ansel Adams and Walker Evans, we still do not manage – in American photography to date – to leave behind us the echoes of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s transcendentalism and Charles Sanders Peirce’s mystical pragmatism.

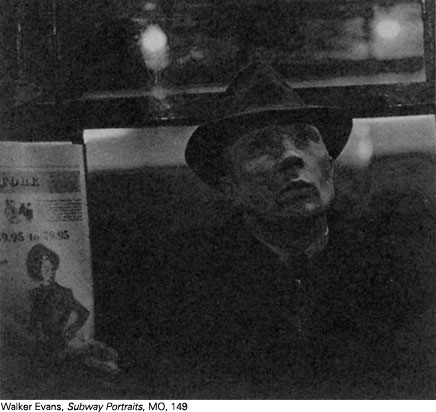

What must have been the change when Evans, consequently, switched from 8 x 10 or 8 x 5 plates – which were fascinating yet burdensome – to the very easy to transport 35 mm that allowed him to photograph travellers on the New York subway? ‘These are assuredly quite different photographic activities’, he tells Student 17, yet the vision-construction is fundamentally the same. As the 1940 Subway Portraits (**MO, 149) show very well, the walls of the subway cars offered his outlook the same referential as the Havana buildings and the walls of the interiors and exteriors of Let Us Now Praise Famous Men: a strict shot that is close, firm, square, solid, and also small enough for the relationship between the show and the image should remain frontal, with the very same bias in relation to the horizontal he had practiced for so long. No, there is a difference. The texture is now smoother with rapid films that detail less the material than the plates, which allows him to introduce the vectoriality of outlooks in the global fluidity. Whitman’s epigraph is then concluded: ‘interiors have their interiors, and exteriors have their exteriors’.

|

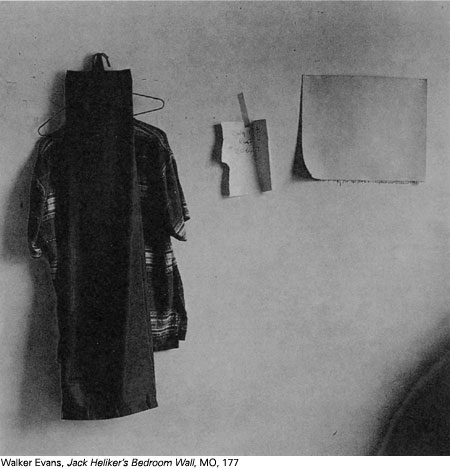

Walker Evans quintessenced himself in a 1969 photograph Jack Heliker’s Bedroom Wall (***MO, 177) in the era of the pop art and minimalism: on the white wall of a bedroom, some clothes are hung on the wall, along with a piece of canvas and a note, pinned on the wall. Let us modestly make a few remarks. (A) Firstly, it is a wall: the wall and the panel accompany Evans’ career as the referential of his magnifying plating. In Havana, he photographed a group of people coming towards him (HA, 80), or indifferent towards him (HA, 26) precisely because they were shot tightly and from above, distributed like a wall. (B) The group of suspended elements not only comprises something written, but also plays on this wall like the writing on a billboard. However, the written mural panel is an archetypal Evans motif. In Looking at Photographs, where Szarkowsky imposes himself to only keep one photograph per photographer, he chooses 1936 Penny Picture Display, probably because all 225 identity photographed placed in superposed horizontal rectangles (3 x 5 x 3 x 5) again create a wall, and because the word STUDIO, standing above the rest in large, encircled rectangular characters (LP, 116) finishes the transformation of this display into a strictly frontal written mural panel. (C) Then, as we know since CARNICERIA (HA, p. 6, cl. 14), the mural writing comprises intense perceptive-motor field effects, and if the clothes, the cardboard, the canvas thereby ‘write’ on Jack Heliker’s wall according to the Evansian graphology, it is because the hung shirt – thereby too large – is covered by the rigid pleats of the trousers that falls off its pleats, mural still. That each pleat of the placated fabric gives, with the neighbouring pleat, a result that maintains the shot tense. That the values (Evans, passionate about the shot of the plate, is an infallible valorist since Havana 1933) compensate each other from every side, and that for this reason, a shadow in the bottom right hand side compensates the pieces of canvas and white cardboard. (D) Finally, as usual, the objects are few enough for the outlook to dominate every relation of tension. The archaeologist finds his happiness there and the artist too. The Whitmanian transcendentalist too.

|

Is it conceivable that Walker Evans should have added photographs by others to his, as is twice the case in Havana (HA, p. 6, cl. 26, 30)? Yes, if they follow the same artistic and semiotic programme. This could specifically occur in Havana in 1933, where the show was simultaneously so constraining and consonating with Evans that it sometimes produced some Evans in others’.

We must not forget the dimension of time and reminiscence of this magnifying archaeology, to the point that Evans’ photographs invited other photographers to come back on the sites, in the sites that he had crossed, in front of. Such was the case of Gilles Mora in 1982, and still of Christenberry. This Alabamian noticed one day that he was born in 1936, the year of the great reportage. He photographed, in colour, alone, or sometimes accompanied by Evans and Friedlander, similar cabins to 1936’s Cabin (MP, 81) and in 1975, the year of Evans’ death, a child’s tomb similar to 1936’s Child’s Grave (MO, 101). These reminiscences have just been published with fragments of the Agee text under the significant title: Of Time and Space. Generally, time follows space. The contrary applies here. And it is good, since it is poetic archaeology.

Henri Van Lier

A photographic history of photography

in Les Cahiers de la Photographie, 1992

List of abbreviations of common references:

BN: Beaumont Newhall, Photography: Essays and Images, Museum of Modem Art.

LP: Szarkowski, Looking at Photographs, Museum of Modem Art.

The acronyms (*), (**), (***) refer to the first, second, and third illustration of the chapters, respectively. Thus, the reference (*** AP, 417) must be interpreted as: “This refers to the third illustration of the chapter, and you will find a better reproduction, or a different one, with the necessary technical specifications, in The Art of Photography listed under number 417”.