KERTESZ (Hungary, 1894-1985)

Photography, because it records indicial imprints, which it obtains in a widely involuntary manner, sometimes favours emptiness, that painting, as it works from stroke to stroke according to a hand and a brain, is tempering, even by the Chinese. However, as our brains detest emptiness, photographers at the outset also have fled this opening, this gap. For the mobilising emptiness to make its entrance, we had to wait until 1900, and for photography to be handled by a child.

9A. Physical emptiness: Lartigue

When an angel flies in Tintoretto’s paintings, it is because it flees the ground. When an object feels as though it flies in Lartigue’s work it is because an emptiness is borne from below or within. The photographic box is miraculous in that sense. In some circumstances, it is enough to orientate it a little ‘too’ low – hence to slightly lift up the motive to the top – to obtain the desired effect, under the condition to use great bands of white – or at least of brightnest – to elide the points of support, and not to forget a few generous obtuse angles. Then, if they do not move, things are in suspension, or in flight.

To this effect, the Belle Époque was not a fortuitous moment. To catch the flight with wonder, one needed the surprise of seeing the first automobiles jolting in the clouds of dust of badly paved roads, the first light airplanes flying a few meters above the ground before landing, the first bicycles combining the independence of movement and the unsteady balance… all this in a constant ‘sporting’ atmosphere. It is the era when painter Vuillard, who was then at his peak, would sometimes leave a conversation to pick up a camera laid down on the corner of a fireplace, turning it God knows where to press the trigger mechanism, and made the trees and paths glide (FS, 121) before ending his sentence.

Obviously, this does not make up a photographic subject, even for Vuillard. Some particular cerebral disposition was required to grasp the emptiness and the skimming over for Lartigue to produce – aged just ten – this historic self-portrait where we see him in his bath. His head is next to the Saint Andrew’s cross of the wide helixes of his water sprayer, both in suspension, skimming over, with the white band of the bath crossing the entire middle plan whilst the water on the front of the shot steals the space from below (*FS, 126). There is no prejudice of viewpoint here (no more privileged reference system, as a physicistwould say around that time): my two little racing cars roll on the floor, it does not matter, for I can place the camera on the ground to photograph them. I will also cover the chimney with a white sheet so as they are caught between land and air (FS, 125). Soon, Cousin Bichonade will fly over a garden staircase (FF, 125), and the jumper will remain suspended between window and ground (FS, 128), a lady, her two dogs and a car that passes them surf on the Bois de Boulogne.

|

This photographic subject, established at the Belle Époque, will continue in the Roaring Twenties. Not only in 1926’s Icaria jump of the young Gérard over his fort, the beach, the sea, and the end of the world (FS, 235). In 1929, just before the Depression, the Jumelles Rowe du Casino de Paris give us a preview into their excellent Charleston (the first dance to say ‘damn’ to the ground) in the way they ‘rise up’ above a car hood ensuring the great white emptiness of the foreground and the famous obtuse angle (**PF, 140). In 1943 still, in Florette à Annecy (PHPH, p. 54), the arms, horizontally spread out at mid-length, play the same role as the bath in the middle distance in 1904. It was a good thing that Lartigue did not pass away before reaching 92 years of age.

|

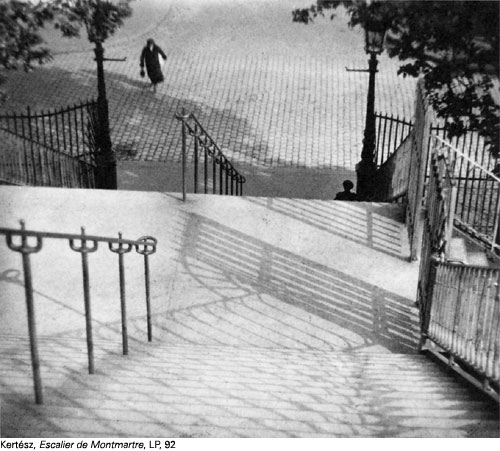

9B. The metaphysical emptiness: Kertész

Yet, there is emptiness and emptiness. Although he was born on the same year, Kertész, who in turn exploits emptiness as a decompression, is a lot less precocious because his intention is more demanding. Born in Hungary like Moholy-Nagy, he also sees everything as a kind of network. However, his bars are principally vertical, and to erect upright a lying body, he invents acrobatic poses (AP, 255) and even the anamorphosis he calls ‘distorsions’ (AP, 258). On the other hand, what arises his interests in these grids is not the full but the in-between, and more precisely the light that is caught and that feeds the in-between as a Substance, in a sort of absolute space where there would no longer be top or bottom, foreground or background. No longer the weightlessness of the flight and the skimming over we find in Lartigue’s work, but that of ubiquity.

This reminds us of something in painting. When Kertész arrives in Paris in 1925, he soon meets Mondrian. The Dutchman’s – whom at first recorded whirlwinds like those of his native plains – painting progressively prepared the ground for this vertical and horizontal turbulence before creating these compositions in rectangles that everyone knows. In the latter, we must see that the original mobility – right up to 1943’s Victory boogie-woogie (a rather eloquent title) which was interrupted by his death – is never lost. All in all, a 1926 Mondrian, at the time when Kertész photographs his studio and sees a vertical network in weightlessness (AP, 248-9), is a certain rotation whose speed is simultaneously nil and infinite ; just like, between 1915 and 1918, a Malevich, through modulated interval of the angles between the oblique parallelepiped, is a translation whose speed were both nil and infinite. Therefore, the Mondrianese colours stick to their end of the spectrum, red and yellow on the one side, blue on the other, since green – median – would have degraded this formidable immobile animation by equalizing the difference of potential, the condition for useful energy. Thus, the theosophical painter pursues in a monk-like rhythm for twenty years, his mandalas (squares in which a rotation animates itself) of WORLD 3. Not those of the Chinese Tao, between WORLD 1 and WORLD 2.

This having been developed, we are now perhaps a little less disarmed to envisage this Escalier de Montmartre (***LP, 92) photographed by Kertész in 1927, and which hands over the hearth of his reasoning. The bars are somewhat thin, diverse in nature, and in groups, in such a way that the light palpitates and trembles everywhere, simultaneously triggering space and decompressing it, almost annulling it. The background somehow hides from view behind the former, but it is not with the aerialist project to derail the objectal identification, but to prevent the gravitation to become more pronounced by a too-lively attraction of what is top and what is bottom. We must look at Kertész’s photographs upside down to grasp just how much the dimensions of the expanse are reversible, consequently the nil weight. The exercise reaches the epitome of its demonstrative strength when we tip Man Ray’s photographs to the side, since the latter also seeks the evanescence through translucency and gleam, but never weightlessness.

|

With Atget, the poetry of the city was found in the semantic depth, in the impressions in the endless exchanges of the cultural cycle. Here, it is found in imponderable quantities of air. Instead of time loosing itself and finding itself as in Atget’s work, or starting to well up, as with Strand, it eternalises itself by thinning – not without interior speed – like the expanse in which it vibrates.

Browsing through the Photo Poche on Kertész – admirably chosen – we realise that his photographic subject – like Dorothea Lange’s – is absolutely constant and patent from 1914 to his death, and to such an extent that we can mention as a key of his photographic subject equivalently a 1953’s hanging laundry photograph made in the United States, or a 1968’s umbrellas in Tokyo (PP, 52), or still, a 1918’s fork (PP, 18). Kerkész, just like Lange, founds his work on a certain angle. An angle is both imperative and recognizable.

|

The title ‘Tulipe mélancolique’ dated 1939 (PP, 27) declares that Kerkész’ mystical rectitude involves humour, the brother of tenderness. Is this why he photographed acrobats (PP, 44) and dancers (AP, 254), which he defined as satirical so much? This creates distant yet curious resonances between his photographic subject and Kafka’s linguistic subject in German.

* and ** © J.H. Lartigue / Association des amis de Jacques-Henri Lartigue.

*** and **** © André Kertész / Ministère de la Culture, France

Henri Van Lier

A photographic history of photography

in Les Cahiers de la Photographie, 1992

List of abbreviations of common references:

AP: The Art of Photography, Yale University Press.

FS: On the Art of Fixing a Shadow, Art Institute of Chicago.

LP: Szarkowski, Looking at Photographs, Museum of Modem Art.

PF: Kozloff, Photography and Fascination, Addison.

PP: Photo Poche,Centre National de la Photographie, Paris.

PHPH: Philosophy of Photography.

The acronyms (*), (**), (***) refer to the first, second, and third illustration of the chapters, respectively. Thus, the reference (*** AP, 417) must be interpreted as: “This refers to the third illustration of the chapter, and you will find a better reproduction, or a different one, with the necessary technical specifications, in The Art of Photography listed under number 417”.