The epiphanic coiling

The 1888 Kodak box and film not only gave photography new powers, but also triggered the implementation of a theory with some photographers. As long as taking photographs had required a competence, as in the era of Hill and Adamson, Nadar, Margaret Cameron, and O’Sullivan, the results spoke for themselves. However, now that everyone could obtain something appropriate, the professionals started to question themselves: we affirm ourselves as photographers, what does it mean? Nadar was furious when swindlers would sell bad photograph at high prices. Now, one felt guilty because everyone, including royals on holidays, could make ‘good’ photos, i.e. that were at least resembling and detailed.

A series of responses ensued. The first was pictorialism, thematised in 1889 by Peter Henry Emerson’s Naturalistic Photography. A photo must exalt an idea by its suspense. Serving its suspense are specific powers: a certain indetermination of the shot, the development, the print. Up to that point, we recognize the program of the European symbolism of the years 1885-1900 reacting against half a century of positivism. However, for P. H. Emerson, the renowned surgeon, naturalist and philologist, the idea to exalt was not melancholy, but the interdependency of tides, plants, animals, strange men and languages, in particular in the wildlife of the farmer of north-eastern and north-western England, because of the immersion in the same linking, unanimous, unanimist shadow, his photographic subject.

Pictorialism starting to wear off, « artist » photographers claimed – at the opposite – a photography in its risks, its bizarre lights, its astounding picture shifts and in particular in the ‘snapshot’, a blind shot by a hunter before a street scene, a building under construction, a horse race. Paul Strand’s The Blind, dated 1916, showing a blind beggar taken without knowing and supposedly without artifice, declares this orientation (FS, 195).

Finally, at the other end, we note that photography was capable of almost-pure abstractions. Here again, we find Paul Strand’s photograph of chair rungs virtually without context (FS, 196; PP, 117), dated from the same year as his blind.

However, Alfred Stieglitz, an American raised in a German Jewish environment, is present in all three tendencies. After having founded his own group in 1902 – Photo-Secession (secession of the New York Camera Club), he creates – in 1903 – the first artistic and theoretical photography newsletter, ‘Camera Work’, which will be published until 1917. The diverse options that we have envisaged are reflected in the publication (PP, Volume 6). From 1905 to 1917, he hosts a gallery on 291 Fifth Avenue, the famous ‘291’. The gallery not only shows photographers, but also some avant-garde artists, from Cézanne to Picasso, Braque, and Picabia. It is there that Marcel Duchamp will show his Fountain (urinal) in 1917. After 1920, Stieglitz will still participate to the ‘Straight Photography’. This wide range of approaches combined with the political talent of ruling over everyone while avoiding arguments, was due to a conjunction of ductility and rigour that his graphology confirms. Deeper still, it was due to a particularly opened photographic subject, where we now sit to hold the lot together.

|

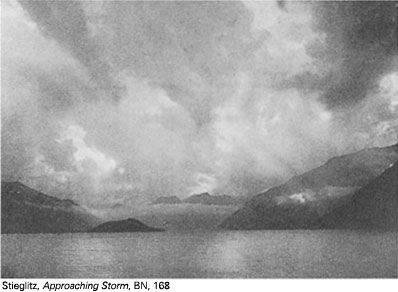

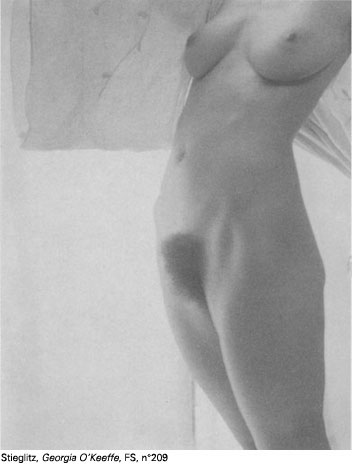

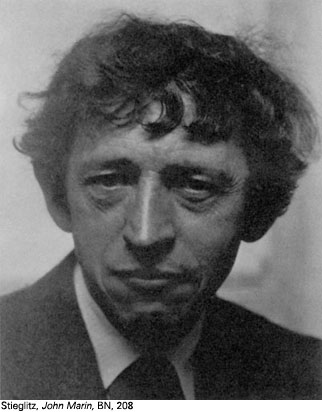

Globally, Stieglitz’s photographer brain constantly considered the – very continuous – photonic imprint as a possibility of rendering contours [modelé, dans le sens de la sculpture et du corps : contours]. For him, the graphic-through-the-light sculpts before it draws or paints. Adding to which that, in a real sculpture – whether from WORLD 1, 2, or 3 – the ambient light exalts a matter with its more or less magical internal forms and mass, whilst in photographical sculpturality – because of the thinness of the paper, the imponderability of the chemical grains, but particularly because of the general floating of the photonic imprint that is disarticulating through its impartial continuity – is no longer the object under the light that appears, but rather, the lighting light. When – for Stieglitz – this light slid on a curve, it turned on itself as it would have done around an object. Then, the person photographed – whilst loosing its heaviness and internal swarming - was not destroyed, but rather it was absorbed, transubstantiated in light. He was epiphanic in the strictest sense of the word. The epiphany through the coiling, weightlessness contours that photography allows was Stieglitz photographic subject.

This subject was actualized according to the three modalities of the sculptural: (A) bas-relief in the bad weather of rain or snow of 1887’s Approaching Storm (*BN, 168); figure in relief in Georgia O’Keeffe’s convexly wrapped naked body in 1918 (FS**, 209), or concavely crouched in 1919’s Torso (PHPH, 133); and (C) high relief in the clothed yet spread across body of Georgia Engelhardt, dated 1921 (***LP, 74).

|

|

The last case is most enlightening. We see how the light is both substance and essence – right up to the architecture and the décor – through its absence of accident, its equality, its firm distribution in vertical and horizontal rectangles (through the Roman pose), by its solidity in the window, and particularly by its coils on the arms, legs, the vase, the leaves. It consists everywhere in itself, with no more distinction of the surface and the background.

Simultaneously, we note that the figure in high relief, out of the bas-relief and the sculpture in the round, is the most suitable for this purpose. Ultimately, both of the above-mentioned Georgia O’Keefe’s nudes are not truly figures in relief if we look at the tight sheet in the former and the bit of arm that appears at a distance from the body in the latter. Hence, Stieglitz’s most stubborn theme is heads as their cubes or spheres had a tendency to cut a leak in the depth. More often than not, he elides or reduces them. If John Martin’s – dated 1920 – is taken whole (****BN, 208), it is because it was sufficiently large and flat to stand out – considering the shadows - in a high relief from the luminous lines of the nose and the collar. We shall compare the regular volumes and the thin strokes of the face with Stieglitz writing to see how a photographic subject belongs to the entire being.

A photographer who is so theoretically conscious was bound to attain almost abstract accomplishments by the end of his career. The Equivalents, produced between 1923 and 1931 (FS 255-7) offer, on a minimal theme of objects, clouds, the existential topology of coils and uncoils of tangles of light, Stieglitz’s photographical subject, in contrast with Coburn’s clouds, that would threateningly (LP, 60) curb from within their inside (LP, 62). We could only expect a testamentary photograph from such a radical subject, a photograph that would combine the essential memory of life and the acceptation of death. It is probably the patch of grass, Grass (FS, 258) taken in Lake George in 1933.

We understand those who would like to see the maturity of photography begin with Stieglitz. He was the first to frankly see that, with the new medium, the being moved from the object towards the light that draped the object. That there were no longer objects but their more or less coiled, more or less dense, or fluid luminous reflections. That the light – coiled or not – did not dispense from the objects, events, or forms (as Victor Meric’s manifesto handed to Stieglitz by Picabia), but assumed them, subsumed them without draining them of their substance. His wife, Georgia O’Keefe, his epiphanies on the film, the pertinent prints do not deprive her of her substance, her flesh, but they reveal her in her very essence. Stieglitz’s light remains substantial, carnal. With such a subject, the perceptive-motor shot effects of photography have rarely had such an almost pictorial coherence. They have rarely been so closely coinciding with the logico-semiotic shot effects they were associated with. Specifically, where should we find more spontaneous concordances between indice (indicium), index (index), analogical referential signs, and digital referential signs (through geometry)?

|

Atget seemed inseparable from Proust. Stieglitz, whose career peaks from around 1900 to 1930, is in tight consonance with Valéry, born eight years later, and who died one year before. On both sides, we observe the same ‘gold’ of the light, the same ‘chain of poses’, the same ‘goals softer than honey’, the same ‘aroma of an idea’, the same ‘cheatingly painted countryside sleep’, the same ‘mass of beatitude’, the same body simultaneously emanating and self-perceived, the same palpation and olfaction of the flesh as a co-penetration of the surface and the within, the same crossing and result of the evanescence of European Symbolism towards carnal ‘charms’ (carmina). And on both sides, the high relief sculpturality resorts to Greece and to Rome. For it is not in Japan, China, or India that the being could have been felt like an apparition, a phenomenon, ‘phainomenon’. Stieglitz and Valéry take the same turn in the WORLD 3 in the dazzled reminiscence of WORLD 2.

* * *

NOTE ON THE NOTION OF PLASTIC EQUIVALENCE IN STIEGLITZ WORK

(The realia of this note are taken from pages 10-11 and 275-276 of Maria Morris Hamburg’s remarkable contribution to The New Vision)

If Stieglitz produces his Equivalents between 1923 and 1931, he has been familiar with the notion of equivalence since 1912. He drew this notion from Mexican political caricaturist Marius de Zayas. The latter, who collaborated at the 291 when he was showing Picasso in the gallery, explained that this painter, deemed revolutionary, did not supply representations of the aspect of objects, but rather, plastic elements triggering – through their strict relations - a cerebral equivalent of the emotion felt before certain objects: « the pictorial equivalent of the emotion produced by nature ». He was referring in particular to natural objects such as nudes.

Stieglitz particularly enjoyed the formula, and at Steichen’s astonishment, bought an untitled, extremely abstract Picasso drawing (NV, 10). He then declared that this drawing was ‘a sort of intellectual cocktail’ for him.

The word « emotion » that Zayas used was not the most appropriate. Yet, simultaneously, Stieglitz enjoys an epistolary exchange with Kandinsky, who publishes ‘Uber das Geistige in der Kunst’ in 1912. There, the initiator and theoretician of abstract art explains - as Zayas had attempted - that it is not because a painting does not show objects that it does not have a content, and that it is not because its colours are hurtful that it [the painting] is not harmonious.

A circle and a square both have a spiritual content (geistig) from because they are a circle and a square ; particularly if they are blue or yellow, as the yellow of a circle is not comparable to that of a square ; even more so if they have a specific position in space. Malevich would soon verify this in the internal (infinite) accelerations resulting from the angular intervals of rectangles between them and the frame. ‘Each form has an interior content. The form is the exterior manifestation of this content (…). There is no form – just like there is nothing in the world – that does not say anything ». Stieglitz is always happy to hear the plain declaration of what every painter has always known, whether his name is Angelico, Tizianno, or Cézanne, and that he himself very well knew. In the 1913 Armory Show, figuring the entire European Avant-Garde, he buys Kandinsky’s Improvisation #27 (NV, 11).

However, in 1912, Stieglitz is persuaded that photographs, these photonic imprints of the exterior world, could not reach the purity of painting. It is probable that he needed a new element to begin work on his Equivalents ten years later. We could think that his nudes of Georgia O’Keefe showed him that the light, in pure epiphanic coils, would suffice to realize his own sense, his ‘emotion’, his decision of existence, his true substance, his ‘geistig’ content.

Assuredly, there is still a difference between the painter and the photographer, as clouds are not « pure » points, lines, surfaces, volumes, shades, values, saturations, textures, and remain exterior physical events. Yet, the clouds were what was closer to abstraction while being consumed with a photographic subject that was specifically the coiling and the luminous high relief.

Henri Van Lier

A photographic history of photography

in Les Cahiers de la Photographie, 1992

List of abbreviations of common references:

NV: The New Vision, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Abrams.

FS: On the Art of Fixing a Shadow, Art Institute of Chicago.

BN: Beaumont Newhall, Photography: Essays and Images, Museum of Modem Art.

LP: Szarkowski, Looking at Photographs, Museum of Modem Art.

PP: Photo Poche,Centre National de la Photographie, Paris.

CP: Special issue of “Cahiers de Photographie” dedicated to the relevant photographer.

PHPH: Philosophy of Photography.

The acronyms (*), (**), (***) refer to the first, second, and third illustration of the chapters, respectively. Thus, the reference (*** AP, 417) must be interpreted as: “This refers to the third illustration of the chapter, and you will find a better reproduction, or a different one, with the necessary technical specifications, in The Art of Photography listed under number 417”.