LOCAL ANTHROPOGENIES - PHYLOGENESIS

A PHOTOGRAPHIC HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY (1992)

ATGET (France, 1857-1927)

Erosion and recycling

We enter the twentieth century - or a bit before - with Atget, and we need to measure the road we travelled so far. In 1887, Maddox replaced the difficultly moveable wet sensitive plate by the dry gelatine plate. In 1880, a New York paper inaugurates the photoengraving process allowing for unlimited reproduction at reduced costs. In 1887, the Blitzlicht-pulver, a powder allowing the flash, is launched. In 1888, Eastman, then aged 35, designs and commercializes the first Kodak box charged with a film reel (paper coated with sensitized gelatine) of 100 views, whose principle he had developed in 1884. The k-o-d-a-k phonics (k-k,o-a,d) evokes both the click and the canning.

Now, anyone can take photographs, anywhere, at any time, under every possible angle: ‘You press the button. We do the rest’. Photography begins to visualize everyday life and intimacy. It becomes a means of scientific investigations on the animal movement with Muybridge and on oscillations with Marey. It supports great inventories on the urban and social transformations induced by the industrial revolution. Atget, who obeyed the official demands of an inventory of the French heritage in its specificities from 1896-98 to his death in 1927 – not only in some generalities – is a confluent of this situation.

To define him, let us remember that photography henceforth allowed to follow the slightest crumbling, disintegration, porosities, the secret invasions of wind on stone and wood, water, corrosions. Atget will use as photographic subject this aptitude of dry plates and chambers of his era and will follow the complete cosmogonist cycle according to which any natural or cultural product builds up, stocks useful energy, intelligence and love. What the physician then names information and neguentropy (Pierre Curie introduces the notion before dying in 1906) simultaneously falls apart in cracks and dust to become waste or to age while still in use, or still, before disappearing into another partial and complete life. In all three cases, it participates to entropy and noise - in the physician’s sense (Henri Poincaré’s appalled page on the inexorable entropy of the universe dates from the same period). This programme does not contradict Nadar’s physiological vision but generalizes it by activating the full cycle: destruction>partial redevelopment>destruction…

No earlier representation would have been capable of following this cycle, not even the extraordinary geological drawings of the Alps by Brueghel the Elder. By lack of detail and continuity, but also because the hand and the brain that produce a painting, sculpture, or architecture introduce construction even in destruction. Velasquez and Goya recorded the decay of the body, Canaletto the discoloring of Venice covered in saltpeter, but always following a domineering view. To the contrary, largely independent from the brain, made up of referential indexes or indexes, photography was capable of recording the slightest modalities of noise and entropy, as well as information and neguentropy, testifying of their reciprocal engendering.

Atget’s photographic subject, applied to an old street, a facade, an alleyway or stairs in a park supposes a particular approach of the motive. Every time, he searched for the point from where nothing stood out or in preponderance, where nothing would contrast or stick out or cut out or center, where everything would be left to its local being, fleeting, equal, both made and unmade, hence very precisely in becoming. The plan of the best definition - which is too declarative - had to subordinate to the depth of the shot by reducing the diaphragm even if it meant chopping the top of a scene. The photonic indices had to lead an existence (indicial) that is as free as possible, decipherable and indecipherable, recycled or de-cycled, without being boosted by any one index. We had moved from WORLD 2 to WORLD 3, like Hill and Adamson, although this time, it was done briskly, without Nadar’s logic-semiotic paradoxes.

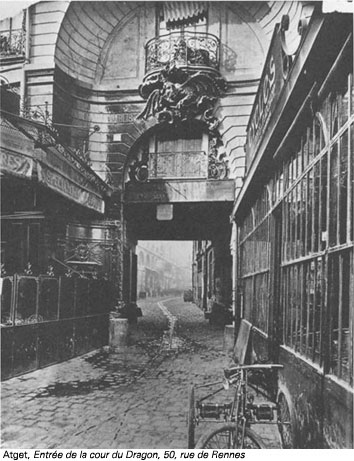

If Atget’s 18 x 24 negatives were detailed, his positive prints were often archaic because of chemistry’s lateness over optics, but also because of the latent intention – using the excuse of « these are only documents » - of keeping them faded and tepid, according to the taker and the taken. Our ‘Entrée de la cour du Dragon, 50, rue de Rennes’ (*) comes from page 33 of Atget, published by Le Chêne/Hachette, which offers 150 exemplary photographs that were printed from the negatives more powerfully than Atget himself would have done. This boost is questionable. Yet, it is more debatable than Mozart played on a Steinway piano by Frank Braley? The primacy of texture over structure - which is an essential phenomenon in Atget’s crumbling and germinal world - is confirmed if it needed to be.

|

We see that there is an Atget rhetoric. Yet it is at the opposite of eloquence. Theatricality too - he dreamt of the stage for thirty years before dedicating his life to photography. But not one that screams on stage, but rather one that haunts the stocks of old stage scenery, pilling up, before and behind the scene, the senses and nonsense of secular semiology; something of the new theatricality (1892) and the new music (1902) of Pelléas and Mélisande. Every defined emotion, every point, every violence, every totalisation would have compromised the generality of the fundamental cycle to the profit of the anecdote, or at least of the event.

Nothing better defines Atget than his contrast with Marville. In 1865, the latter photographed the same themes, streets, places and parks but with a completely different photographic subject, seeking sharp fronts and angles (**PN, 108), discontinuity (PN, 70), the decision, the contrast, the index frame, the non-publicized separation of plans (AP, 68), immobile time, mirroring (AP, 74).

|

Atget was impossible before his time. Let us recall the little interest granted by the Ancients to the cultural cycle, with the exception of Ibn Khaldoun in a context that is not purely historical. For Chateaubriand to perceive – around 1800 – the depth of past time (the ‘tradition’ in the Confucian acception is at the opposite of a spatial time) a revolution as radical and outspoken as the French revolution, the seism of the first industrial revolution and ultimately the presentiment of an evolutionary geography were all presupposed. Spencer will need another century to vulgarise a generalised evolutionism with its concomitant lives and deaths, and for Curie and Poincaré to question the couple entropy / neguentropy as principle of universes. Among the artists, a fervent, silent, and imponderable recollection begun in 1885, engendering the surimpressions of the European Symbolism without Proust’s. Yet, let us note that it is only with the Proust of Swann’s Way, with its grey phonics and syntax made up of carnal and fluid compenetrations of moments, (those too of the Bergsonian length) that Atget is consonant. The dates are pitiless.

Atget would not have been possible without Paris. Paris is a city like no others. It is, just like Rome, a patent case of the cultural recycling, yet it does not have Rome’s creative and destructive fits and starts, and its cataclysms are less grandiose. The desegregation and rehabilitation affect the most globalizing architecture, the most daily carnal ever. Atget - theater lover and unfortunate painter until he reached forty - probably found there, in the stock of calmly, secularly recycled stage sets by his photographic subject, the essential photographic subject of painters and dramas that he had dreamed of previously, in vain.

His strolls in the city, assigned by official and private commissions and some elements of luck, show how the photographic subject calls on photographic themes or motives, not the contrary. Atget will manage never to show the Eiffel Tower, that escaped the cosmogonic cycle in its young days, but whose skeleton – with more hollow parts than filled parts – would never be propitious to shed a good light on this cycle. On the other hand, Notre-Dame could be tamed under the condition that it was shot from the other side of the water through winter branches, where, as immense as it might be, it would only appear as being in a desagreged-reagreged state of a wider cycle. This is how he dared to approach it in 1925, two years before he died (FS, 244), and three years before Proust passed away.

Paradoxically, Atget was also a contemporary of analytical and synthetic cubism and the passage to atonality. In a nutshell, the huge revolution of the WORLD 2 to the WORLD 3 occurred according to two main trends. Those that went beyond the Greek totalizing ‘form’ to the profit of functioning elements while breaking the ‘form’ according to the path of discontinuation: Rimbaud, Mallarmé, Picasso, Schönberg. Others operated the same de-centering by overlapping compenetrations according to a continuous path: Bonnard, Dubussy, Proust, Valéry, and Bergson. Just like Stieglitz that we will meet shortly, Atget follows the second path.

Henri Van Lier

A photographic history of photography

in Les Cahiers de la Photographie, 1992

List of abbreviations of common references:

PN: Photography until Now, Museum of Modem Art.

AP: The Art of Photography, Yale University Press.

FS: On the Art of Fixing a Shadow, Art Institute of Chicago.

The acronyms (*), (**), (***) refer to the first, second, and third illustration of the chapters, respectively. Thus, the reference (*** AP, 417) must be interpreted as: “This refers to the third illustration of the chapter, and you will find a better reproduction, or a different one, with the necessary technical specifications, in The Art of Photography listed under number 417”.