CAMERON (U.K., 1815-1879)

The internal milieu and transcendent fulguration

An uninterrupted succession of technical invention soon allowed reaching, in the multipliable negative-positive process – or calotype-talbotype – a definition of the image rivalling with that of the daguerreotype with its unique copies.

This generated great perplexity with the English photographers. Eastlake, whose wife we have just met through her portrait by Hill and Adamson, presided (in 1853) over a stormy session in his recently founded academy, during which painters-photographers split into two camps. The first camp, so-called Pre-Raphaelites, accepted – in the name of painting - the new detailed image. They thought that they were witnessing an ancestral desire for objectivity. The latter, so-called Moderns feared the fine definition, also in the name of painting, from which they particularly held onto the freedom and peculiarity of conceptions. Among the latter, William J. Newton had recommended putting ‘the whole subject a little out of focus’ to uphold the subjectivity that was threatened – in his opinion - by the exactitude of the rendering. This was the beginning of the forthcoming pictorialism, of which Peter Henry Emerson created the theory in 1889.

2A. The internal milieu: Nadar

In France, Nadar – whose photographic fervour begins in 1853 - extracted new detail from the negative-positive suite from all other consequences. He used it to follow the physiology of bodies in every state.

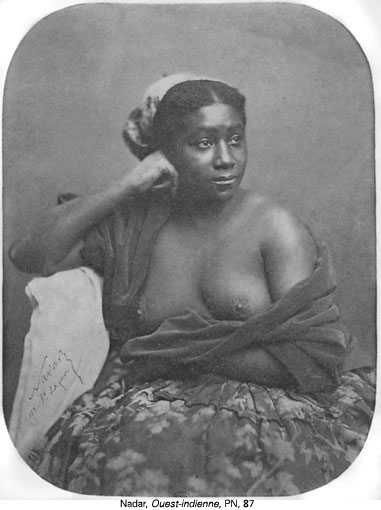

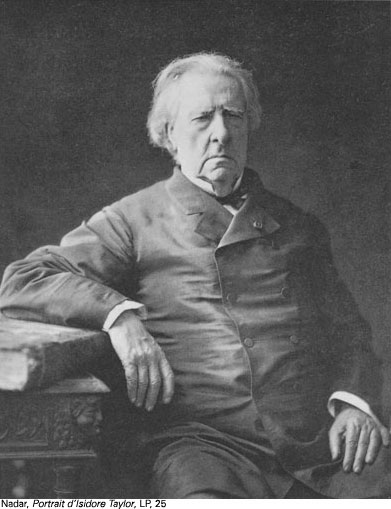

Van Eyck’s Canon Van der Paelen presents a skin accident as a status statement, old age and a venerable wisdom, whereas other painters saw it as a picturesque mark. For Nadar, it was the manifestation of the internal work of an organ or of energies, like in the case of his West Indian girl, dated 1854-59, whose breasts are rounded to the buds of their areolas (PN*, 87). At other times, it is a manifestation of its wearing out, like in the example of Isidore Taylor (the MOMA’s copy – dated circa 1865 (**LP, 25) -is reproduced here). No anecdote. Skin accidents are the manifestation of latent, underground forces exempt of any external influence. Even when Nadar photographs a city, his vision grasps from below, from within. Once he fully masters artificial lighting, he photographs the Parisian catacombs and sewers in 1860 (Eugène Sue had completed the Mystères de Paris in 1844). When he will turn to aerial photography, it will be to grasp, in one single view, large panels of the earth in its skin.

|

Simultaneously, a movement is seized. Obviously not an exterior, recent movement, since, at the outbreak of the American civil war in 1861, American photographers had to abandon the idea of photographing combats and make do with their prodromes and sequels, as the exposure time was measured in seconds. However, Nadar’s exposure time grasps organisms doted with an internal and potential movement exalted by immobility because it targets muted energies. Henceforth, the genius that romanticism had supposed as coming down from the heavens, now became the result of a particularly intense or particular biological thrust, a principal movement manifested by external and successive gestures. Of course, this is what the Latin ingenium had aimed at, an inbred lot (PP, 18, 23). Nadar’s photographs of the times are not so much of women and children, deemed too smooth and available, but rather of men with their marked faces.

|

An appropriate centring, one that showed the latent, muted movement of the physiology needed to be elected. The main thing was not to let oneself be dispersed: faced to a standing or seated body, Nadar – who usually takes several frames per session – captures what occurs between the knees and the skull, sometimes between the hips and the skull, as the latter finds space to shine in an often-vast, top hollow. For the rest, since the thrusts are latent, the body must invent itself with the minimum of accessories. Sometimes, this means that the photographer has to greatly intervene in the clothing – not specifically in the choice of attire that is part of the inventing body, but to set alive a pleat here, disguise another one there – to obtain such pleating that the twists and turns of the fabric should clad closely and continue internal virtualities (PP, 23). Sometimes, they continue the shape of a seat, a table, a draping (PP, 2, 4, 44, particularly 9) and it is not negligible that the twist of a [furniture] leg should move up towards the left (PP, 11) or the right (PP, 13). Of course, there was a trance before the pose. It begins with the verbal or written command and ends in the studio, amongst a maelstrom of preposterous exclamations, documented questions, demonstrative gestures. Physiology for physiology, the shooting is a clinch (PP, 62). The excellent composition of the illustrations of Photo Poche’s Nadar shows this very well, particularly as it is shorn of ornaments.

Nothing best explains the appearance of Nadar’s ‘physiologies’ than their contrast with anterior daguerreotypes. Those, as they were originally in negative, worked as relics in the full sense, since the photons that touched the portrayed were the same than those that had touched the plate that we, in turn, touch. Such sacramental presence produced a delimitation and a congealing that was appropriate to the voluntarism of puritan American. The documents compiled by Beaumont Newhall in The Daguerreotype in America (Dover, 1961) show the portrayed as set in his interior or exterior environment. However, it is the possibility of going this extreme of the body’s signature, and showing the autonomous latencies of organisms through the detail of the collidon, then the gelatinous silver bromide, that became Nadar’s photographic subject in a historical moment attentive to latent forces.

In 1855, Claude Bernard established physiology while meditating over his Introduction à l’étude de la medicine expérimentale (1865). The thesis of the latter is precisely that every organism is an ‘internal milieu’ that is not subject to actions others than of himself on himself, just like in a poisoning, it is himself that poisons himself through a poison. The notion of energy – particularly useful energy – is proclaimed just after 1850 with the two principles of Clausius-Carnot Thermodynamic. The idea of competing energies animates everything, from the industry and monetary speculation to geology and biology and the shaping of species: Origin of Species is - a suffocating swarming of mineral and physiological forces - is published in 1862. Maxime Du Camp, who went looking for the preparatory photographs with Flaubert, was close to Nadar. Strangely enough, the latter brings a boil to his fermenting bodies while the essence of chemistry works with ferments. Pasteur is determined – against the opinion of Berzelius (who introduces ‘catalysis’ in 1837) – to have the process of fermentation depend off a ‘vital’ force of the ‘live’ ferment.

Very soon – just like the Jules Verne of the Journey to the Centre of the Earth, dated 1864 -, several photographers moved from the physiology of live bodies to that of the whole earth as an organism in its monstrous thrusts at Yosemite Valley and Yellowstone. O’Sullivan’s famous photograph where gas vapours and earth’s crust escape through the crack of Streamboat Springs is dated 1867 (FS, p. 32).

However, Nadar’s role as the privileged actor of such a strong historical moment that it should suffice to his glory, does not explain the deflagrating character of his Portrait of Isidore Taylor (**LP, 25). Further to the internal physiological movement, we must note the frankly pictorial pose - and more precisely the bourgeois pictorial pose, that of Ingres’ Portrait de Monsieur Bertin, dated 1832 – in the declared suite of the left hand leaning on the thigh, the right arm on the book, the head on the chest, and the whole figure on the seat. The organic and cultural circuit is almost architecturally complete: the citadel of sensory organs in the face, the depressed machinery of the lungs, the bloated stomach pulling apart the tails of the frock coat that shines on a gaping openness of shadow, the detailed table, the heavy book and the text that we suppose important. The indexation of the essential focus ends with the directional lighting. Was such composing pictoriality an episodic concession to the fact that Taylor, who wrote for the theatre and several travel books before becoming a senator – was in relation with Ingres, whom he had asked for some illustrations? Partly. But we must see that this type of effect is subjacent everywhere in Nadar’s work. For instance, in one of his portraits of Baudelaire, as the latter was finishing the Fleurs du Mal in around 1855 (FS, 77), we note that the bias lengthened torso, the right arm and the top of the armchair make up a triangle that is both steady and floating, whose potential movement is in consonance with the poet’s language subject, as could be the case for a great portraitist painter.

Let us get to the heart. This conjunction of pictoriality in the composition and of photographicity in the detailed physiological inscription provokes a logic-semiotic torsion for Nadar that we should stress, as it will become a constant motive of photography.

Indeed, a painting is elaborated by a hand that answers to a brain with each trait, as it refers to analogical referential signs (images) and sometimes in digital referential signs (texts or digits) which are joined by indexes (lat. indices), pointings, vanishing lines, and diverse accents. Simultaneously, the painter is able to create highly coherent perceptive-motor field effects. There are very few – if any – indices (lat. indicia) when traces of impatience or returns in the stroke appear. In a nutshell, a painting designates, demonstrates, refers to when it is figurative, but also when it is non-figurative. In the later case, its referent is topology, cybernetic, logic-semiotic (‘abstract’ or ‘concrete’), making up the painter’s pictorial subject.

At the opposite, a photographer can only capture indices (lat.indicia), the imprints of photons reverberated by an external event. And simultaneously, its perceptive-motor shot effects can only be weak and not very coherent. Nadar can titillate Isidore Taylor’s cuffs to set off their white sparkle hence creating a certain gravitating perception between them, the collar and the nose. He can even – in the MOMA’s print reproduced here (**LP, 25) keep the combination of arabesques and chiaroscuro used by Ingres – and that the subject must have liked – through the extraordinary precision of the Woodburytype (an ink print from a copper engraving preserving all its values): the pleats of the clothes and the traits of the face play their own game, escaping, drifting. A photo is made up of indicia, the photonic imprints. It proposes, exposes, betrays, shows, surrenders. It only refers-to by a few rare and floating indexes, such as directional lighting, frame orientations, vanishing lines or still, the attitude suggested to the motive. There are stronger – and more innovative - perceptive-motor shot effects in just one of the hands of the Louvre’s Monsieur Bertin than in Isidore Taylor as a whole.

Hence, when Nadar boosts picturiality by the most Ingresque composition and photographicity through the physiological detail – which fatally disperses the perceptive-motor field effects –, he provokes a torsion, a logic-semiotic curvature, which triggers in return a thwarted perceptive-motor field effect that springs up and escapes simultaneously. Hence the deflagrating effect of Isidore Taylor, where the explicit allusion to Ingres forces the distortion, distension, to the climax. Nadar’s photographic subject is the potentialities of the psychological latency period but also this constantly stirred up contradiction, with some peculiar semiotic field effect.

It took many factors for Nadar to be possible. In Jules Verne’s 1865 novel, From the Earth to the Moon, the author – who deemed him with a ‘lion’s head’ because of his red haired mane - changed the photographer’s name to Ardan (an anagram of Nadar) and granted him with ‘wonderment, this instinct that brings some temperaments to be passionate about super-human things’. Nadar – or Mister Tournachon then Tournadard, then Nadard and Nadar – was the son of an editor-librarian in Lyon. All his life, he will be passionate about journalism – particularly theatre chronicles. He starts off by working as a caricature artist after attending a few medicine courses, hence comforting the physiological outlook that others share with him around that time (Essay de physiognomonie by Swiss Tôppfer dated 1845). The 249 famous figures of the 1854 Nadar Pantheon testify of this viewpoint as do even more some preparatory drawings like this sketch of Balzac, where the paintbrush boosts up the internal pressures of daguerreotype he bought from Gavarni (***Nadar, Hubschmid, 893). However, Nadar touches photography to prepare his drawings, and soon notes that it serves best his extra-scientific vision. He will only draw to retouch his proofs with a pencil. He develops artificial lighting, takes the first aerial photographs, and, in 1863, commissions the building of The Giant, a 40-metre high balloon. When the latter takes off for the second time in the presence of Napoleon III (that the good socialist he is holds in contempt), the outcome is a catastrophe. His legs are broken, while his wife, the entrepreneurial Ernestine, has her thorax smashed in. He nonetheless continues to exploit the Giant until 1867 and comes back to work as aeronaut during the Paris siege. Simultaneously, he praises the virtues of ‘the heavier than air’ with the support of Victor Hugo and our Isodore Taylor, and of course, of from the Earth to the Moon Jules Verne. He exults when Blériot crosses the English Channel in 1909! This hormonal [man] only feels at ease in the hubbub of artist and scientists, who, in the era of Bohemia and Dandyism were powerful animals made to enter straight into his photographic subject. In his studio, he will house the two first impressionist salons of 1874 and 1887.

|

Apart from that, Jules Verne was right: « wonderment » excludes « acquisivity » and therefore engenders some disorder. No sure datation. From 1870, who did what? Himself? His son Paul? His wife Ernestine? And when it was him, was he alert, hunting, or fulfilled? Lions quickly move their paws and digest slowly. Photography? It is « this prodigious art that, with the applied electricity and chloroform, makes our nineteenth century the greatest of all centuries »; but an 1892 letter to his son Paul speaks of indifference, aversion, and even horror.

These sudden changes of mood are not incomprehensible. Nadar is in love with physiology. As an organism, Nadar was himself the place of deportments, new starts and the most violent depressions. A genius with his hands, he is bored whenever he can do something too easily. But, above all, if he no longer jumps before or behind his camera obscura, it is because at the end of his life, in around 1900, there is no-one likely to wake him up by bouncing up before him apart from Chevreul, the chemist of the stearine candle and the simultaneous contrast of colours, who is over a hundred years old when Nadar questions him in 1886. If only luck had made him bump into Rimbaud! Or into Verlaine before his decline! How could he sign with his lion leap signature ‘Nadar’ on the pale bodies of a young Proust or the 1890 symbolists, such as Mallarmé and his Méry ‘pink blond with golden hair’ when he had met the physiologies of Gautier and Baudelaire, whose preparatory drawing of the Nadar Pantheon captures a glance that no-one had ever imagined (Nadar, Hobschmid, 895)? The abundance or lack of game is also part of the historicity of a photographic subject, hence of a photographer.

2B.Transcendent fulguration: Margaret Cameron

Since 1863, Margaret Cameron, born in India, educated in France, and settled in England, has acquired a taste for photography. She also rubs shoulders with exceptional characters, and counts in her circle of friends Lewis Carroll, famous photographer logician of the greatest logicians, i.e. little girls; Carlyle, who exalts heroic men in the German fashion; John Herschel, who enumerates nebulae and specializes in double stars. However, it could not escape these sublimed spirits that photos, proceeding from light to form – and not from form to light as in painting – had a proclivity to extricate ‘figures’ in the biblical sense, meaning some large vertical, horizontal, diagonal orientations of space that were more sacred and transcendent that they were bare, elementarily contrasted, more general.

Margaret Cameron made photonically engendered ‘figures’ in that sense her photographic subject. At the time and in her circles, the subject had to relate – apart from biblical themes – to some astronomical symbols such as these two kissing children entitled, with a veiled reference to John Herschel, The Double Star (AP, 59). Our Child’s Head, dated 1866 (****AP, 61), which is figural to the extreme, does not hold a particular psychology, yet, in its archetypal circularity, it delivers the combat light/shade, that will be interpreted as day/night, good/evil, life/death, yes/no, present/future, present/past, Christianity/paganism, according to the faith. Of course, John Herschel and Carlyle’s faces, radiant with light from within, became in turn figural (AP, 62, 63).

In the strictest sense, the figures establishing themselves from the dawn of photography will remain ever-present in its history, and we will find them, secularized, in the work of Duane Michals and Ralph Gibson, near us. On the other hand, are they not underlying in Nadar’s work? To all that Isodore Taylor forced us to say concerning its deflagrating character, should we not add the frank, elementary, specifically figural cut created by the photonic reception of the lighting? The arabesque is not unrelated to figurality in this Ingres transfer.

|

Henri Van Lier

A photographic history of photography

in Les Cahiers de la Photographie, 1992

List of abbreviations of common references:

PN: Photography until Now, Museum of Modem Art.

AP: The Art of Photography, Yale University Press.

FS: On the Art of Fixing a Shadow, Art Institute of Chicago.

LP: Szarkowski, Looking at Photographs, Museum of Modem Art.

PP: Photo Poche,Centre National de la Photographie, Paris.

The acronyms (*), (**), (***) refer to the first, second, and third illustration of the chapters, respectively. Thus, the reference (*** AP, 417) must be interpreted as: “This refers to the third illustration of the chapter, and you will find a better reproduction, or a different one, with the necessary technical specifications, in The Art of Photography listed under number 417”.