I give you the photograph as the equivalent of what I saw and felt, is just about what Stieglitz said by 1900. For me, the word "equivalent" is of great importance. It is centrifugal, a flux of forces directed outwards, not centripetal.

ANSEL ADAMS, Polaroid Land Photograph, 1963, 1978.

As with all other techniques, photography poses the question of the nature of the link between equipment and human activity in general. The humanist illusion suggests that equipment is a means in the service of man, and in his control. However, from the very start, our objects and technical processes are objects-signs, or objects-indices, and we are signed animals, literally constituted by them through our languages. Furthermore, devices are not so much a means as a milieu; and a milieu we are steeped in rather than it being at our command. In fact, photography nowadays comprises millions of apparatuses and billions of photographs and lenses. It might be we who push the shutter, but, as we have seen up to now, it is, above all, we who are triggered.

There is something peculiar about speaking so extensively of the photographic act. One hardly speaks of the musical or chemical act, let alone the automotive or aviating act. One started to speak of architectural acts and the act of writing the moment architecture and literature faded. However, the photograph is in prime health. Why then do we use this curious theological term (God is pure act), which language employs when stressing the interiority of an action (act of faith, hope, contrition) as opposed to exterior ones (the offering of thanks, or thanksgiving), or action and reaction in physics? It is perhaps because it concerns a domain where human action is at once most violent and most decentered, in case of the surgical act for instance. Both surgeon and photographer cut and trigger. And both operate on the level of living humanity, and engage with a specific death. The one works predominantly with bodies, while the other predominantly engages with signs. Apparently, photography puts us in the realm of the human par excellence, i.e. representation and the graph (cf. graphein). Photography appears the most blatantly anthropocentric act, but this is without accounting for what the photographic apparatuses we produce state quite bluntly: "Put us down somewhere, allow us to release the shutter by ourselves, we will manage to make you something, to produce things often better than you have, which you will never understand absolutely anyhow, as you are concocting mostly anthropomorphic, thus irrelevant theories. And are you even sure you are dealing with representations and graphs? Nothing is more inhuman (indifferent to human plans) than an imprint, no matter how indicial to your eyes, and even though indexed by you."

Therefore, we will use the phrase photographic behavior, without denying the link between the photographic and surgical act, and without failing to recognize that there are scientifically, artistically, commercially, and erotically committed photographers. Following from the indicial and therefore overlapping nature of the photograph, these behaviors will not be as distinct and separable as is the case with sign systems. In addition, it will also prove difficult to clearly distinguish the one who makes the photograph from the one who looks at it. Thus, we will consider them together when addressing the major attitudes or behaviors. Our approach will inevitably be eclectic, and it is in an almost arbitrary order that we will artificially treat each one of these behaviors.

By pragmatic we refer to anything achieving practical aims in the common sense of the term. As the previous chapters suggest, the photograph has this capacity insofar as, through the exploitation of indexes and superficiality of field, it can function as an imprint-indicial, and especially as a stimulus-sign and as a figure.

13A. MODERATE VOYEURISM

Above the table, on which a line of fabric samples had been unpacked and spread out (Samsa was a traveling salesman) hung the picture which he had recently clipped from an illustrated magazine and inserted in a pretty gilt frame. The picture showed a lady sitting there upright, bedizened in a fur hat and fur boa, with her entire forearm vanishing inside a heavy fur muff that she held out toward the viewer.

KAFKA, The Metamorphosis

The photograph is the pornographic tool par excellence, provided we can agree on terminology. Let us agree to name sexual those objects, texts, sounds and images that supposedly induce orgasmic behavior and which mix, without prior exclusions, bodies and signs. The erotic is then that which evokes orgasmic phenomena by favoring the sign extracted from it. The perverse is that which splits signs and behavior subject to prior exclusions. The obscene is that which brings things back to the side of the sign and its articulation. The pornographic is that which intends to provoke orgasmic behavior, or at least orgasmic imagination, in its functioning as a stimulus-sign.

In fact, pornography brings about the textual presentation or imaging of organs and objects which are in part signs. However, pornography also releases sign systems that function to the extent to which they are perceived as sexual, perverse or erotic. At once determinate and isolated, pornographic themes are supposed to provoke an action by themselves, infallibly and independent of all contexts, in the manner a stimulus-sign can trigger off a reaction. The fact that the pornographic is widely distributed - often in millions of copies - is supposed to support this automatic character of their power.

There was hardly any pornography in the contemporary sense prior to the nineteenth century. There was only an erotic literature in the work of Rétif de la Bretonne, a perverse literature with Sade, the sexual in the intense plays of Malherbe and the obscene in Rabelais. In the nineteenth century, a behaviorist psychology developed, which facilitated the advance of pornographic themes. Rightly or wrongly, his theory maintained that orgasmic behavior, even in humans, could be explained by triggers and stimuli. At the same time, industrial production allowed for massive distribution, thus guaranteeing effectiveness. So a true design of pornographic texts, objects and images was instituted, with real or imagined feedback from the reactions of customers.

|

The Krim's : Ten, Dark, Sweet Ponds, 1979, "Zien", Rotterdam.

|

The photograph played a decisive role in this development. We have seen that it can organize itself as a stimulus-sign. It is prodigiously multipliable owing to the collusion of its digitality and its printing screens. The photograph's characteristic of image-imprint gives it an advantage over text and even over the sculpted pornographic object, due to the fact that, in the photograph, the "natural" stimulus-sign is seemingly present without "representation". This dictates its specific rules of design. Whenever human figures appear in a photograph, they will necessarily show stereotypical expressions and gestures that have no relation to what actually takes place. If this were not the case, true situations with all their interpretative complexity would be recreated, destroying the effect a simple stimulus might provoke. Moreover, it is important that the layout is not fluid, containing only a minimum of perceptual field effects. These two requirements explain a contrario why it is difficult to make pornographic cinema: luminous movements immediately create true situations, that is to say, sexual, erotic, perverse or obscene situations. And it is not easy either to take a pornographic Polaroid, considering that a Polaroid's glaucous (even distant) depth restores a continuity that turns towards the sexual.

Furthermore, pornographic photos have other advantages. Their stimuli, while they are all efficient, are never too numerous. This way, customers can make use of them in a serious or playful manner, according to the mood of the moment. Pornographic photos are the luminous imprints of preexisting spectacles, but which are now arranged according to a superficiality of field and a wholly abstract photonic tactility. Industrial multiplication later confers authority upon the pornographic photograph through the effect of number, while trivializing it at the same time.

In this way, the pornographic photograph lends itself to what one could call a moderate voyeurism. In its most intense form, voyeurism is a perversion that in advance excludes certain modalities of touch, particularly that of contact and the reciprocal gaze. However, there is also a less exacting voyeurism excluding nothing, and which often is able to be held into view in order to make the eye-brain nexus function as though there were a remote touch and contact, the kind that takes place among city residents. In addition to a true form of pornography, which can be found in specialized publications, photography has developed a light-hearted sort of imagery which can be found in Playboy, Penthouse and Lui. More specifically, in these magazines we can find pictures that are not sexual, perverse, obscene or pornographic but only timidly erotic. However, one can also formulate this differently. Present-day scientific and technological society is not particularly perverse. Through the transpositions in which it excels and its absence of substantiality, photography would like to count amongst its social functions that of being the last shelter for perversion, as an important cultural motor. That is, in a suitably neutralized form: a passive and empty perversion.

The rest is a matter of culture. One shouldn't be surprised that the West developed a horizontal voyeurism, a voyeurism through the keyhole, in accordance with a situation dear to Sartre. In sharp contrast, the Japanese, as the descendants of Utamaro, explored all violent and innocuous possibilities of a protruding voyeurism, like when someone is hanging upside-down from an alcove while centering himself by the ceiling's beams.

13B. POSITIONING IN ADVERTISING

The Prop's the Thing.

Time Magazine.

The photograph is almost as closely linked to publicity as it is to pornography. Here as well, the photograph not only serves but also partly creates and develops as a milieu and not merely as a means.

Firstly, there is short-term publicity, which is made for a product or an event without much longevity. It tries to draw attention to something by praising its merits. It is a blend of shock and seduction, thus resembling the photographic mechanisms of pornography. One looks for signs or object-signs that speak by themselves independent of any context. These photos are marked by a rhetoric of overtly decipherable indices, making them look orderly or disorderly, subtle or botched, depending on the audience. Nonetheless, there is a difference with the pornographic image. In the latter, objects are supposed to be "naturally" attractive and stimulating, while "shock publicity" only attracts a particular culture and target group. Thus, the use of photographic stimuli-signs in advertising shows a diversity lacking in the pornographic photography.

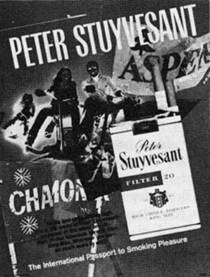

However, large advertising productions do not envisage short-term but long-term goals. They concern products, services, political parties and religious groups that promise themselves a long future for. What matters in this case is the positioning of what is presented, that is to say its distinctiveness, its difference within the technical and social network over a long period of time. Long-term publicity not only transmits the positioning of social goods but also performs it. It has as function to signal that what is announced is something distinct from all the rest and more particularly all the other products that belong to the same field. It is not important that Marlboro, Kent, Peter Stuyvesant or Dunhill should be appealing since they all are, as they are sold all over the world. It is pivotal that they be enticing in a manner different from each other. That is to say, what is important is the distribution of the particular attitude or look of the desire to smoke in a given society at a given period in time. Likewise, it is not a question whether Mitterrand, Giscard, Chirac or Marchais appear as promising - which they, as politicians, are already anyways by definition - but that each one of them is perceived as such in a manner differentiating the one from the other three. This can be done to the point where, by putting together the areas the four politicians occupy, one can almost recover the entire image of France's political desires of the period. How does the advertising photograph have a hand in this operation?

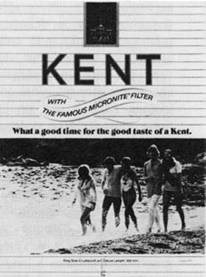

Surely, by its primary denotations, which we can interpret as having a more lasting effect as they do not simply present themselves as mere stimuli-signs but rather as figures. The secondary denotations all pertain to the same order: i.e. youthfulness, at ease, competence, energy and risk-taking. These all belong to moods, to the tonalities of existence. As far as connotations are concerned, that is to say, those signs attesting to the frames of mind (hygienist, competitive, traveling) of the transmitters or receivers, they can be very marked in a political advert or in publicity for a bank, but are less so elsewhere: the Gitane cigarette presents itself as regional and working-class, while Kent and Peter Stuyvesant are presented as international and upper-class, and while Marlboro overlaps these distinctions. Furthermore, the essential aspect of long-term publicity seems to reside in the perceptual field effects it triggers, or rather, it institutes. Furthermore, this could explain why connotations are often hardly marked in the case of long-term publicity, and why denotations take the form of figure-signs rather than stimuli-signs.

The positioning of what is announced through perceptual field effects is perfectly exemplified by the cigarette adds of the seventies, just before the stress on nicotine and tar levels evened the circulation of desire. The three international brands most widely sold were divided along three major western categories, namely space, time and becoming - or, to be more precise, centripetal location, centrifugal flow and the all-out becoming of travel, which apply to Marlboro, Kent and Peter Stuyvesant, respectively.

As for the perceptual field effects retained (indexed) in the photograph, for Marlboro it is that of closed space, closed off above and by the background, centripetal and dense, heavily scented and in browns turning red. The direct and indirect denotations, as well as the connotations, are effected by a horse led by a mature cowboy returning home. The text echoes the words: where and country indicate place, come to indicates centripetal movement, flavor indicates the smell and a strong flavor in the mouth. In addition, the syntax, in an outspoken centripetal fashion, places Marlboro in between two groups of identical phonemes: come to (kvmt) and country (kvnt), whose repetition and strength are reinforced even by written form, where the central Ib of Marlboro appears clutched between two groups of letters of equal number close to mar oro.

By contrast, the photographic field effect of Kent is time as an imponderable and horizontal flow, suggested by the pastel tones, dominated by white crossed by evenly horizontal blue and gold lines. With respect to direct and indirect denotation, and with respect to connotation, the photograph shows healthy male and female youths against an aquatic backdrop. Again, the text merely makes the image explicit: time (instant), what a good (exclamation in accordance with the instantaneity and singularity of the moment), taste (the flavor as captured in the moment, not in its substantial density), with two t's playing the role of relay in the sequence t-d-t, th-d-t-t-, kt: What a good time for the good taste of a Kent.

Peter Stuyvesant resumes the thesis of place and the antithesis of time, and ends the dialectic by resuming the two in the synthesis of the voyage. The perceptual field effects are held within an angle, namely that of the plane taking off, and by the variegated colors favoring the complementary invigorating reds and greens filling the equally variegated and never clear-cut forms (drawing on Rauschenberg's tears). In short, this is a kaleidoscope of a world seen through airports. Regarding the direct and indirect denotation, apart from the plane, it would not be suitable to have clearly defined faces or objects, but only those evoked through a gliding movement (again similar to Rauschenberg). The connotations are subtly colonial. Textually speaking, there is no clear catchword for conveying an effect that is so unstable, so transitory except than to turn to the most kaleidoscopic word in English: joy. Any particular message would delimit the voyage. The name is enough: Peter Stuyvesant, evoking one of the founding groups of New York City, i.e. the Dutch, indeed, the Flying Dutchmen - as air travelers.

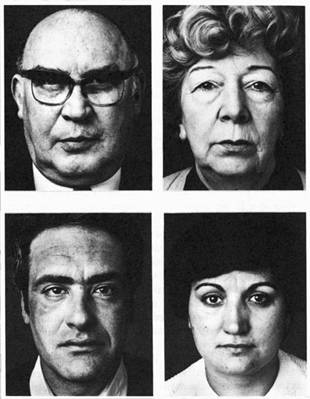

Similarly, the French elections of 1981 presented the candidates in an almost exhaustive system of perceptual field effects. Mitterrand: shot in sfumato and depth of field in front of a wall, lightly slanted. Marchais: his back to a wall and frontal. Giscard: in a frontal shot along the mural plane, with superficiality of field. Chirac: shot in three-quarter compared to the surface and depth. These are the denotations and connotations that arise: Mitterrand's misty look coming from afar and looking into the distance; Giscard's lucid look following the passer-by; Marchais's active look directed towards the one coming to the appointment, and Chirac with his eye on the target. This system was so complete that the other parties could not be but reduced to small parties.

We have elaborated on these examples a bit further because they clearly define the notion of positioning, and also because they show the strict program to which the advertising photographer must conform. The adequate functioning of things is so precarious as to require a duo, and even a trinity: the creative team, the photographer and the artistic director. Based on the briefing handed to the creative team who improvised on it, the photographer tries to find suitable field effect, as well as fitting denotations and connotations. However, there is need for an outside judge, i.e. the artistic director, who will decide whether the acquired shots do indeed truly correspond to the positioning. The artistic director must ensure that the shots function at most as variations and do not alter the system of differences determining what is announced. The layout itself is part of a well-defined space-time configuration: profound, stable and warm in Chanel, torn (scratched) in Christian Dior, turbulent in Revillon, baroque in Lanc™me.

This allows us to specify the long-term objectives of advertising photography. Surely, it does not aim at being distasteful. It acknowledges that its mission is not to be agreeable or to resort to the proven arsenal of violence and sex. Occasionally, short term publicity makes use of simple techniques. But neither the most arousing negligee nor the most terrifying revolver can do anything for Marlboro, Kent or Peter Stuyvesant or for any of the candidates for the presidency of the Republic. On the contrary, if a female style were to be sterile or harmful to a petrol brand pretending to put "a tiger in your engine", it at least must agree with the "shell I love", since the shell, the female theme par excellence, is part of the imaginary positioning of a corporation that originally transported sea shells. Thus, at first, long-term publicity does not try to seduce, to persuade, to inform or to embellish, but to make present an actual or potentially interesting difference within the system of products of a society at a given time. Therefore, we should not be surprised by the permanence of long-term publicity, a permanence equivalent to social permanence. The positioning of Coca-Cola has not changed in a hundred years. In publicity, what psychologists call impregnation is not a simple relation between form and substance as is the case with animals. On short term, it concerns stimuli-signs and with respect to long term, it concerns figures and even stable perceptual field effects, of which images are only modulations.

When all is said and done, publicity is as ancient as man since man is the signed animal, for whom goods are attractive only when placed in sign systems. The novelty of the present is that publicity within an industrial society is industrial itself. In a technological and commercial network of billions of products distributed amongst billions of customers in a synergic planetary network, publicity requires a cheap prop perceptible to all. Whether in Europe, America or India, this vehicle can only be the photograph, radio or TV. The latter is the most powerful since its images are acquired through the transmission rather than the reception of light, endowing the advertised product with its own energy; the TV image is animated by a similar force as Goldorak. However, the simple photograph also has its virtues.

Due to its fixity, the photograph maintains a close relation to the packaging and the written name of the product, which, in a many cases (as with cigarettes, toothpastes, washing powder, and toilet soap) are a significant part or essential to the product itself. On the other hand, it is the advertising photograph that surrounds the city and the streets, and assures the public insertion of certain particularly important products (cars, food and politicians) in the technical network, which has become the foundation of our society. With its light and sound, the billboard now plays a significant urbanistic role. It succeeds even better because it is extremely transposable and because the denotations and connotations are often or subordinated to blurred perceptual field effects. This way, the photo establishes local climates, microclimates, as it corresponds to an envelopment all architecture aspires to. Having become monument, or having replaced the monument, the billboard signals that in contemporary society great commercial, political and religious products are more important than great men. Unless, in their turn, the latter are great products or great events themselves.

|

13C. THE MORTAL GAME OF FASHION

If I were allowed to choose among the books to be published a hundred years after my death, do you know which ones I would pick in this library of the future? Oh well, it would not be a novel or a history book, my friend. I would simply take a fashion magazine to see how women dressed a century after my passing. And these flounces would teach me more about the future of humanity than all the philosophers, novelists, preachers and professors ever could.

ANATOLE FRANCE, preface to The Psychology of Clothes by Flugel. Vogue Covers, 1900-1970.

Nothing illustrates the notion of (perceptual, motive, semiotic or indicial) field effects better than fashion. In fashion, the idea of a code is merely a ruse. Everyone knows that the recommendations that could pass for rules (pleated shoes, skirt cut off at the knees, low waistline, more or less cleavage) are issued only after the fashion of the year already exists. These rules are a result. And besides, they are not made to be followed. They exist so that a vague discourse allows one to speak and to be attentive to a line, which is very precisely a curve, a particular modulation. It is a matter of the eyes, it is said, or the fingertips. Here, traits, volumes, colors, saturations, luminosities, and often luminescence mysteriously become compatible. This is not the case with texts, or even cinema or television. Here, there is an absolute need for the stability of photographic field effects. This is accomplished through the particular capability of the photograph to create figures, as we have defined them with respect to the photo-novel.

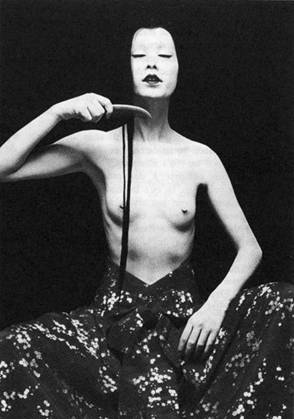

These considerations would undoubtedly have sufficed provided there only was an everyday and familiar fashion, namely that of Marie-Claire or Elle. But Vogue and Donna oblige us to offer more vertiginous propositions. Here, one can see that fashion is sometimes, and perhaps always, a harsh game of life and death revolving around the recapture of the fragile and unstable biological body into fixed analogical and digital signs, even on the verge of ceremonial ascendancy, of which the funerary apparatus would be fashion's latent ideal. Within the signed animal lurks the desire to be as "wise as images," or even as wise as imagos, that is to say, doubles of the dead. The Egyptians and Etruscans realized it full well. And this engenders new collusions with photography, which is also an authority on life and death in its exceptional capabilities of congealing, of giving shape to absent presence, of refusing to surrender. Here we encounter a tempered necrophilia as a form of moderate voyeurism, often shared by the connoisseurs of photography and the admirers of models. In this case, photographs do not have the function of doubling real clothes and bodies at all. It is rather the clothes and bodies that double the photographs. In this Venetian carnival, the mimes willingly mimic the negatives of the negative.

|

Photo Hideki Fujii by GIF

|

When Vogue, for its public that understands the meaning of fashion, celebrated its 1900-1970 birthday, the magazine contained no text, but only cover photographs. In it, Nefertiti appeared as photographed by both Richard Avedon and Irving Penn. The intentions of high fashion have undoubtedly not changed since the days of the embalming practices in Egypt. The photograph, equally embalming, is merely allowed to develop and transmit these intentions. The Japanese Fujii and Hiro demonstrate the same merciless bias to its antipodes.

13D. THE SENTIMENTAL EUCHARIST

Rare photographs, resembling him as old family portraits resemble disappeared and anachronistic ancestors. Frozen, hieratic, beautiful. He did not like photographs.

CATHERINE CLÉMENT, The Lives and Legends of Jacques Lacan.<

Sentiment is not synonymous with emotion. It does not contain violence or transience. It enjoys what lasts. But also what is kept in halftones. Somewhat absently present. A somewhat present absence. Occasionally with pangs and measured grief. Becoming attached to tiny curvatures and modulations. The photograph functions very efficiently within this behavior, at least in Europe. And it is with respect to the photograph that we have to measure, not without casuistry, all the subtleties of realism and anti-realism.

Let us have the courage to momentarily take up these necessary quibbles. There is something discomforting in a portrait photograph: photons have touched a film, and these photons have also touched a person. This means that a photograph is a contact surface for fragments of someone's reality (the inflection of a smile, ankle, or handshake) and also a contact surface for the materially real elements of someone (his or her aptitude for photonic reflection, the combinations between photons and the physiology of his or her body). But this photographic contact surface is mediate, carried out at a distance by mediating photons. It is also abstract, as these photons were selected according to focal lengths and especially according to a superficiality of field. This situation implies both an addition and a loss, as in one and the same touch sight is expanded but simultaneously reduced by the distance inherent in vision. This vision is augmented through touch, but reduced because of the inherent (obscene) proximity of touch. Simultaneously, this visual contact surface attempts to attain the real and the reality of the spectacle by laying hold of both outside of place and duration in an only physically determinable space-time, which, provided it does not compromise the real, exiles reality. Thus, the real and the reality of a person captured in the photograph were never in the mode of reality to us, and neither were they ever for this person. The photographed person is a state of the world irreducible to any other, just as any other photographed object. It specifically passes the moment the photograph is taken. The photo is a one-time-never-again, but we are unable to situate the spectacle in an actual duration, as opposed to recollections. In a word, the photograph does not show an apprehension, a perception or imagining within itself. As a major trigger of mental schemas, the photograph can only provoke waking dreams or reveries on itself, or, in other words, starting from its surface. To write "in memory of" underneath a photograph is not an explanatory caption, it is a complement or a compensation for what a photograph is not.

|

|

|

Henriette de Wael en 1900

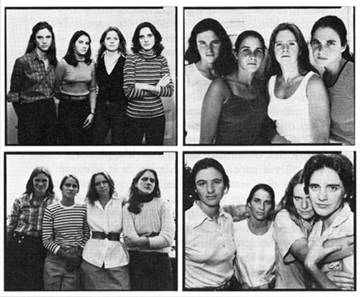

Nicolas Nixon Pierre Radisic |

In the photograph, the oedipal practice tries to reinforce the aspects of personal presence. While accepting a certain distance in time (that has been), it strains to deny spatial abstraction. Thus, the exterior cause of indices, i.e. the spectacle, is understood as a referent, a messenger sending (or being) a message, even a message without a code, divine speech, fatum, a divine nod of the head, numen. By predilection, this speech originated from lovers and loved ones, in particular from the parental couple, as the physical and moral origin, as justification and redemption of a viewer who regards himself as the sole and intimate interpreter of the secret (my reading of my mother's smile will die with me). As the photograph resists this treatment, through its abstractions and field effects, the sentimental bias especially details of a photograph - a detail, almost denotatively and connotatively defined that grants us the essence, the point, a pang, the punctum. Surely, Kafka was right when he said that the photograph is too superficial to endure the progressive exposures sentiment enjoys so much. Captured within this desire, the photograph calls for writing, the pleasure of the text, in the form of a tireless correspondence in Kafka's case or the fragments of an amorous speech with Barthes. In any event, everything is held together far away from the camera obscura and the black box in the almost insomniac Camera Lucida. One will have noted that a reading of details with an almost stellar intensity is particularly marked in male homosexuality, as manifested by the British poets of The Male Muse, the lively decoupages of Hockney's jointed photographs or Mapplethorpe's deposed unravelings.

But there is a non-oedipal usage of the photograph that we can call equally sentimental although it is cosmological. It is a case of tracing, in the pell-mell or the family album, the dissemination of resemblances and the miniscule, disparate and fleeting encounters of microscopic and gyrating traits configuring the photograph. And indeed, how, according to these luminous imprints, could this here, once having been that, have become this? Is a person, or does he become something? Or are there only singular moments, whose sequence is attached to a first and last name, and which we accordingly call the life of this person? The photographic interrogation of the species is equally radical. Which traits are yours, and which come from someone else? Which biological traits and which cultural traits do these twin sisters share, these parents and grandparents, these children, these monovular twins? But, again, isn't there a multitude of traits? Is not each one of them, as in Borges's The Approach to Al-Mu'tasim, an incidental and instantaneous encounter of imperceptible mental and physical spores, coming from the most distant and most scattered beings, along centuries and distant continents, and which only characterize a family because they are present more overtly at a given moment? Contemporary biology sometimes contends that life originated from cosmic clouds of particles capable of triggering vital events by virtue of particular local conditions. Does the photograph, through its sheer number, pattern, indices in overlap and the ability to transpose, not show that signification and meaning are always merely the fleeting precipitations from a cloud of infinitely small possibilities that are joined more or less fortunately at a certain time and place, and as such can never be pinned down? The pell-mell, as the word points out, makes us understand this dissemination better than the album.

The photograph is therefore the privileged instrument of the oedipal family, but it also partakes of, and more pertinently so considering its nature, the dissolution of the mommy-daddy-me triangle. To the industrial migrant laborers, to all the nomads of our multiple journeys in body or mind, the photograph warrants a minimum of temporal and spatial references. But how? The mixture, on walls, of diverse relatives and showbiz stars creates an alternative family. So, it is less a matter of blood relations than mental relations. Our sociability without society fits well with this comet-like dissemination of physical and mental traits.

Henri Van Lier